It was inevitable that Mary Evins would take the path she chose in life.

“I always knew I would have a Ph.D. and be a professor,” said the MTSU research professor of History and coordinator for the American Democracy Project who has residency in the Honors College.

It was also inevitable that her life would focus on history and citizenship. Born to natives of DeKalb County and Warren County whose roots extend deeply into Tennessee soil, Evins grew up listening to tales of family history. Both sides of her family settled in the hills and hollows of Tennessee in the early 1800s.

“I loved taking in all of his stories,” Evins said of her father, Joe L. Evins, who represented Tennessee’s 5th District (1947–53) and 4th District (1953–77) in Congress.

The right to vote is fundamental to citizenship. The struggle for it has been constant throughout our history.

Born after World War II in Washington, D.C., Evins was referred to around her household as the “post-war product.” She would accompany the family, including mother Ann and sisters Joanna and Jane, between life in urban Washington and life in rural Tennessee throughout her childhood, essentially attending school 11 months a year because of the difference in school terms between the two areas. In Washington, which was filled with political and diplomatic families, Evins went to school with children whose parents were household names across the U.S. and with children from countries around the world.

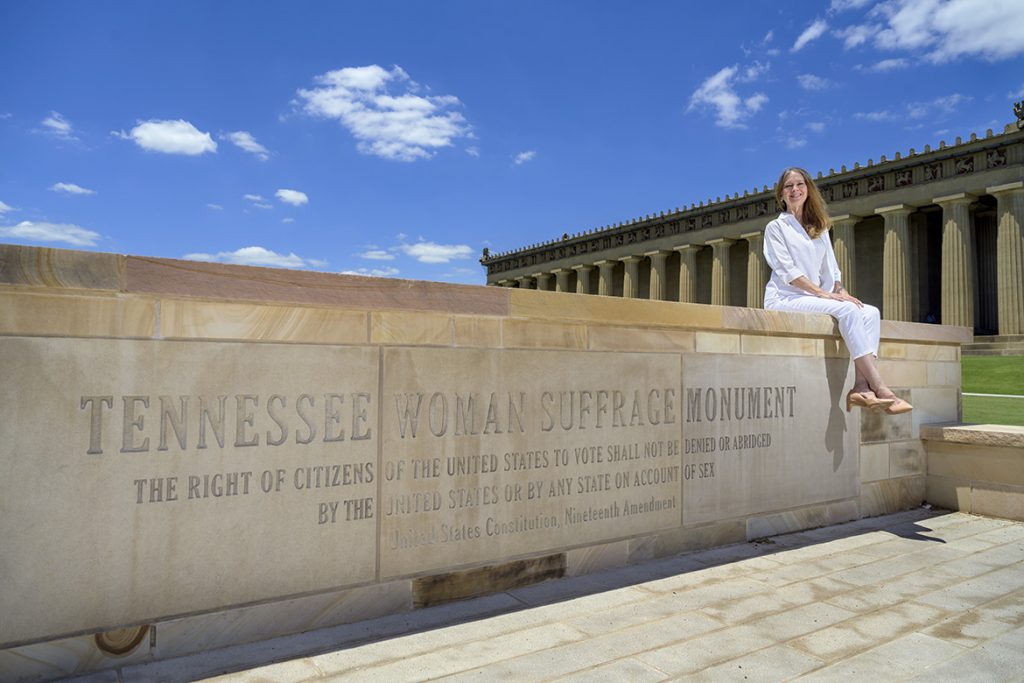

Mary Evins, History resident faculty in the Honors College and director of MTSU’s American Democracy Project, at the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument in Nashville’s Centennial Park (photo by Andy Heidt)

“We would drive back and forth from D.C. to middle Tennessee many times every year in the Buick with the dog and the goldfish bowl,” Evins said. “It was a two-day trip in those days. I have rich memories of the winding backroads of rural Tennessee and rural Virginia before the interstate system.”

It was these urban-rural, North-South, foreign-homegrown dichotomies that would come to shape Evins’ life and her approach to the American experience.

DIGGING INTO THE PAST

Both sides of her family were steeped in politics and education over centuries, with officeholders and teachers in every generation. Her grandparents taught in one-room schoolhouses. Her great-great-grandfather was one of the founders of the Cumberland Female College in Warren County in 1850. Her mother’s father was the legendary Circuit Court Judge R. W. Smartt, who served on the bench in Tennessee around 45 years and held court in counties across the state.

“All the Smartt children read Latin and great literature by the fireplace on the farm in rural Warren County,” Evins said, “and all went to college, even during the Great Depression.”

It was natural that Evins’ mother, Ann, after graduating from Warren County High School and earning her bachelor’s degree from Maryville College in east Tennessee, would teach school. Her mother’s first job was teaching English and Latin at the high school in Smithville, which is where Ann met Evins’ father.

Yet, as much as she loved history, Evins also dug archaeology. Double-majoring in History and Anthropology and minoring in Classical Studies, she worked on excavations throughout college. She participated in her first dig in the Middle East, in Iran as an undergraduate at Vanderbilt University, and excavated in Iran as a graduate student as well.

I have been a cultural translator my whole life really. I learned early on to bridge differences.

It was while she was at Vanderbilt that inevitability again entered the picture. The university required seniors to write out their life plans. Evins did so, in a notebook that was rediscovered many years later in the Evins family attic in Smithville. In her handwriting, the notebook predicted that she would work after college, get a master’s degree, teach high school history for a few years, then get her doctorate and be a university professor. She did all those things.

Evins’ Honors history class role-played dual parts for the Chicago 1968 political convention: (l–r) front, BriAnna Jones, Olivia Guse, and Madison Staggs; back, Jacob Moore, Nathaniel Lathrop, and Jaia Peterson. (photo by Andy Heidt)

After obtaining her undergraduate degree, Evins worked at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, then returned to Tennessee and earned her master’s degree in education, again from Vanderbilt. She taught in Tennessee public schools for a few years before entering the Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago, earning a second master’s degree and her doctorate.

Having grown up in Washington, Evins did not find big-city living in Chicago intimidating. However, some of her contemporaries were not accustomed to being around Southerners.

“There were not many Tennesseans going to university in the Midwest,” said Evins, who was always pleased to invite her Northern colleagues to visither family back home in Tennessee. “I have been a cultural translator my whole life really. I learned early on to bridge differences and navigate among those whose biases and stereotypes narrow their ability to understand.”

Helping people navigate differences and grow beyond their preconceptions would serve Evins well in later years when teaching university students who were not only new to higher education and the college experience but who also often lacked knowledge of people from different regions, cultures, heritages, languages, and religions—the kinds of people Evins has been privileged to know throughout her life.

CONNECTING TO THE PRESENT

At the University of Chicago, Evins worked under the mentorship of anthropologists Robert Braidwood, on whom the Indiana Jones character was based, and Robert McCormick Adams, who would assume leadership of the Smithsonian Institution during the Reagan administration.

Evins earned the 2019–20 Honors College’s Exemplary Faculty Service Award.

Evins did her dissertation research in Turkey because politics had intervened.

“The reason I shifted from Iran to Turkey—I had studied Farsi for two years in order to be able to work in Iran—was that by the 1980s I could no longer go there,” Evins said. “After the Iranian revolution, there was a massive exodus of American and British archaeologists out of Iran and into Turkey.”

For four years she excavated as a graduate student in southeastern Turkey near the Syrian border, on the Euphrates River, before returning to the States, to Chicago and to the Smithsonian as a pre-doctoral fellow, to complete her research and writing.

Evins’ first jobs after obtaining her doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1998 were adjunct professorships at Tennessee universities, and she was hired as a temporary assistant professor in 2002 at Tennessee State University. She joined MTSU’s Department of History in 2005, was promoted to associate professor in 2008, moved into the research track at MTSU in 2014, and was promoted to research professor in 2019.

Evins with a statue of Tennessee suffragists at the monument in Nashville (photo by Andy Heidt)

It was during her early years of teaching history in Tennessee that Evins first began studying and writing on Tennessee women in social reform during the Progressive Era, women who were involved in race, class, and gender challenges to socioeconomic and sociopolitical structures in Tennessee at the turn of the last century.

These women started the associations and laid the groundwork for the political activism that would culminate in Tennessee’s ratification of the 19th Amendment. Evins’ anthology Tennessee Women in the Progressive Era will be followed by Constructing Citizenship: Tennessee Public Women next year.

Making classroom study personally relevant to students is what good professors do.

Having been part of Tennessee’s first service-learning faculty-training program during her time at TSU, at MTSU she was an early adopter of on-campus and off-campus experiential learning for her classes—for community-based learning, civic learning, connecting history to everyday life, and working to make textbook knowledge have real-world meaning.

“Embedding enrichment opportunities into coursework and making classroom study personally relevant to students is what good professors do,” Evins said.

IMPACTING THE FUTURE

When then-MTSU Provost Kaylene Gebert and fellow historian Jim Williams, then-head of the American Democracy Project (ADP) on campus who was preparing to take over the Albert Gore Research Center, invited Evins to attend an ADP conference in Baltimore, Evins’ life was transformed.

“I was swept away by that conference. It was filled with passionate faculty focusing on teaching for meaning. It provided a framework and structure for what I knew in my core to be true, that civic learning is potent best practice in higher education,” Evins said.

Evins speaks at the 2020 Middle Tennessee Campus Civic Summit.

The American Democracy Project, initially begun under the auspices of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities in 2003, unites nearly 300 public institutions of higher education in a network designed to help students become actively engaged in their communities and in our participatory democracy.

To that end, Evins’ primary objective has been to advance civic learning and civic engagement across the disciplines at MTSU.

“Mary’s leadership of the American Democracy Project has been outstanding,” MTSU Provost Mark Byrnes said. “She consistently arranges programming that is timely, relevant, and engaging. And her work on voter registration has been indefatigable.”

It’s absolutely imperative that civic learning not be . . . saved for celebratory occasions.

Evins rallies MTSU students to promote visible, audible appreciations of the American experiment. Faculty, students, and staff celebrate Constitution Day each Sept. 17—the day in 1787 that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention signed the United States Constitution in Philadelphia—with public readings of the foundational American document across campus to refresh its significance.

“U.S. history is baseline for every American as we interact with our friends and neighbors here at home and in other lands,” Evins said. “It’s our starting point.”

During election years, ADP pulls out all the stops to encourage voting, whether hosting the Tennessee Campus Civic Summit in 2020 complete with panel discussions and national and state workshops or promoting free Raider Xpress shuttles to the polls on Election Day. Voter registration is a constant theme, and Evins rallies students to become civic-minded year in and year out.

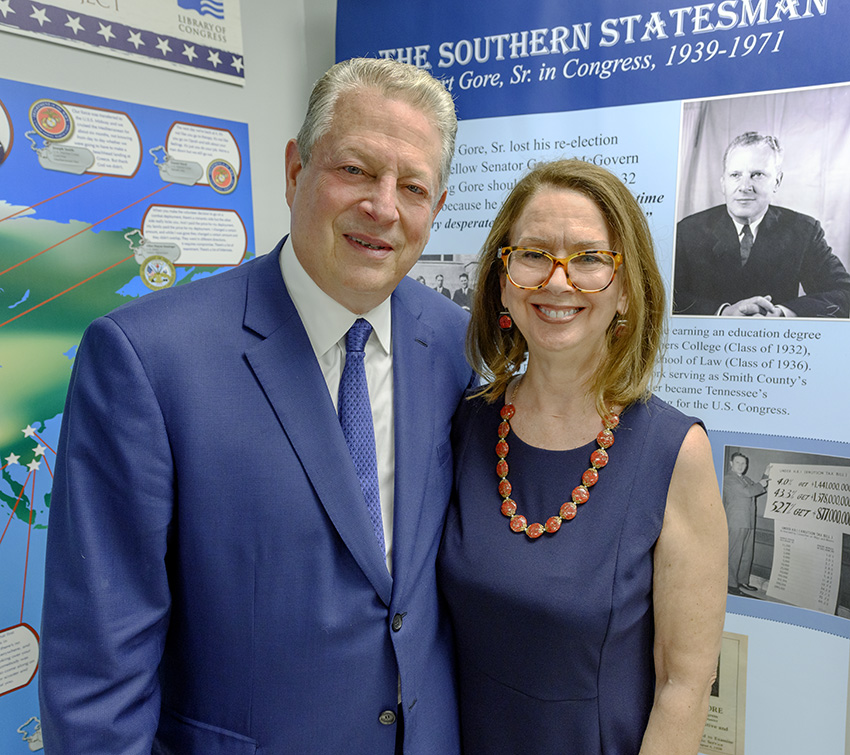

Former Vice President Al Gore and Evins at MTSU’s Albert Gore Research Center, which is named in honor of his father, an MTSU alumnus who also represented Tennessee constituents in Congress

“We need to meet each incoming class with renewed freshness, energy, and focus,” Evins said. “. . . It’s absolutely imperative that civic learning not be just episodic or saved for celebratory occasions, but that it be embedded in everything we do on a regular basis.”

“The franchise is the key to how democracy works, and it is beyond my comprehension that any American would work to limit citizens’ access to the ballot,” Evins said. “Voting should be easier and more readily available to citizens, not difficult and restrictive.

“We want to help our students to be able to vote while they are under our care. . . . The practice of voting secures students’ commitment to active citizenship and voter participation for the rest of their lives,” she added. “Eighteen-year-old Americans must be supported when they first engage as voters, not be confused, undervalued, and deterred. Voting is the most basic act of being American.

“The right to vote is fundamental to citizenship,” Evins continued. “The struggle for it has been constant throughout our history. African Americans sought the right to vote. Women sought the right to vote. Eighteen-year-olds sought the right to vote.”

The words flowed from Evins freely, sincerely, and spontaneously. The American idea, a glorious experiment that has been a goal and in a state of disequilibrium since inception, is her passion. Yet, as an educator, she says allowing oneself to be vulnerable enough to endure some disequilibrium is the state in which we learn the most.

“That’s the only way to communicate with any other human being—through the heart.”

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST