(Editor’s Note: In 2013, News and Media Relations staffer Gina Logue wrote, submitted and delivered an essay at the university-hosted Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference, which was held in the James Union Building. “Hank Aaron: My Childhood Hero” was about the impact that rooting for Aaron as he chased Babe Ruth’s career home run record had on Logue’s childhood and the way she saw baseball and the world in general. Hank Aaron passed away Friday, Jan. 22, 2021, at his home in Atlanta at the age of 86. Logue’s essay is presented to you here in remembrance of a man whose quiet confidence and courage in the face of hatred remains an example for us all.)

Many people remember 1968 as the year opposing forces in the United States reached critical mass. It was the year the counterculture peaked in both positive and negative ways before being co-opted by the establishment in the Seventies. Bullets claimed the lives of Martin Luther King Jr., Robert Kennedy and 16,899 Americans in Vietnam. The Democratic National Convention devolved into chaos as Mayor Richard Daley’s storm troopers took a “kick ass first and ask questions later” approach. The Summer Olympics in Mexico City were engulfed in demonstration fever as American track stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in the air on the medal stand to protest the state of black America, while Czech gymnast Vera Caslavska lowered her head to protest sharing a gold medal with an unworthy Russian, whose country had invaded Czechoslovakia that spring.

Gina K. Logue

Many people, including me, remember 1968 for all those things. But I also remember it as the year I became an Atlanta Braves fan. And out of that fanship was borne my juvenile hero worship of Henry Louis Aaron.

Before we discuss Hank, though, let’s set the scene.

Developing the habit of listening to Braves’ games on the radio became a Southern rite of passage quickly after they moved to Atlanta from Milwaukee in 1966. Before that, viewers had only NBC Television’s Game of the Week and an occasional St. Louis Cardinals feed on whichever station the Redbirds had picked up as an affiliate in the market. And, while I knew enough about the Cardinals to know that their lineup had Lou Brock leading off, followed by Curt Flood and Orlando Cepeda (until Cepeda became a Brave), they never really captured my imagination.

Atlanta-based newspaperman Lewis Grizzard understood. In a column datelined Dothan, Alabama, Grizzard explained how hearing Ernie Johnson Sr. call a Braves game on the radio soothed his anxiety one night when he became lost on a country road. He knew that if he could still hear the Braves game, wherever they were playing, whoever they were playing, however poorly they were playing, transmitted through the ether, he would be all right. The Braves were a touchstone, a talisman, something a Southerner could grab onto and call his own or her own while the country fought and bitched and went to hell in a handbasket.

Hank Aaron, surrounded by reporters and photographers, hugs his mother, Estella Aaron, after hitting his 715th career home run in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium on April 8, 1974, to break Babe Ruth’s record. (Baseball History Comes Alive)

Back when “clear channel” meant an AM connection with the rest of the country instead of an uber-capitalistic curse, radio was a lonely kid’s best friend. My friend Radio introduced me to a new friend, the number three batter in the Braves’ lineup. Through my friend Radio’s descriptions, I came to know Hank Aaron as a man who took his time. A man with a compact musculature, economical in its use of skin. A deliberate man who took his time limbering up in the on-deck circle, walking at a moderate pace, almost ambling to home plate, bat in hand, putting his helmet on his head only after entering the batter’s box and only after he felt comfortable doing so—yet accomplishing all this without delaying the game one second. The synchronicity of Aaron’s gait with the nature of the game itself meant he could feel just as much at home in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium as in his hometown of Mobile, Alabama, where he swung at rolled up rags because he and his playmates could not afford a baseball.

When the Lincoln-Mercury Division of Ford Motor Company offered a series of prints of famous athletes painted by LeRoy Neiman, I sent away for them immediately. I ditched most of them, but two adorned my bedroom wall in Shelbyville, Tennessee, well into my 20s. Over the guest bed, I posted Bart Starr of the Green Bay Packers. A true son of the South—graduate of Jefferson Davis High School in Montgomery, Alabama, star quarterback under Bear Bryant at the University of Alabama, the kind of guy who rarely ever said a cuss word, according to teammate Jerry Kramer, and whiter than Hellman’s Mayonnaise spread on a slice of Wonder Bread.

Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s home run record of 714 career home runs by hitting number 715 in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium on April 8, 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

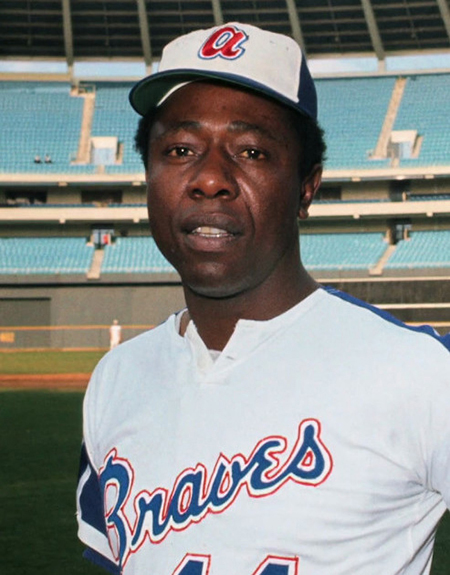

Over my bed, I posted Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves—clear-eyed, compact, one of seven siblings, survivor of the Negro Leagues, World Series MVP in 1957, and contender for his sport’s most unapproachable record—career home runs, secure in the Bambino’s grave, or so the sports media thought.

When it finally dawned on reporters that Aaron was statistically within reach of Babe Ruth’s all-time mark of 714 homers, it was as though someone had roused that guy sleeping in the nosebleed seats after years of beer-induced slumber. People knew who Hank Aaron was. They knew he was one of the best hitters in baseball. But he went about being superior in such a workmanlike manner that it was if the whole baseball world had taken him for granted after he left Milwaukee.

Now, all of a sudden, here comes Aaron after the Babe. Aaron hits home run number 537, propelling him past Mickey Mantle on the all-time home run list. And he does it one day before my 12th birthday—July 30, 1969. Given the superstitious nature of baseball players and baseball lovers, it just had to be an omen.

For the first three years of the Seventies, all the talk was “Can he do it? Can a black man do it?” The closer Aaron got to the mark, the hotter the racist rhetoric became. His daughter, Gail, who wrote for the Nashville Tennessean for a time, was afforded protection while a student at Fisk University. Aaron’s elderly parents in Mobile were answering phone calls at 3 in the morning only to hear the coward on the other end hang up. The FBI was brought in to sift through loads of hate mail and death threats.

Now, I didn’t get any death threats and I didn’t get any hate mail. But my appreciation of Hank Aaron was interpreted by some of my peers and some of their parents as what some racist Southerners called “jungle fever.” After all, when other girls my age put magazine photos of Bobby Sherman and David Cassidy on their walls and bulletin boards, why would I stick a huge Leroy Neiman print of a black man on my wall? I must have a crush on Hank Aaron, and you know what that makes me, right? This was in an era when the only sex education some white girls got from their parents was to be told not to let a black boy carry their books home from school because they’ll get taken off into the woods and raped. A good many people seemed anxious to see me have a fatal wreck at the intersection of Race and Gender.

Like Hank’s quick-wristed swing, my appreciation of my hero was more nuanced than that. And, at the same time, it was all so simple. If Hank Aaron could survive all the hell the world could put on him and his family just because he was better at hitting a ball than anyone else in the world, I can stand anything anyone imposes on me, I told myself. Why should anyone have the right to tell me who my heroes should be or what they should look like?

In this undated photo, Hank Aaron concludes his classic swing at bat in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. (Baseball History Comes Alive)

Perhaps a more direct connection between fan and hero can be found in the moment Hank surpassed Babe Ruth by hitting number 715 off Al Dowling of the Los Angeles Dodgers in Atlanta on April 8, 1974. You’ll no doubt recall the two young men whose enthusiasm outstripped their common sense as they tried to join Aaron in his home run trot. But not that many people seem to recall the first thing Hank did after he made it through all his congratulatory teammates. He hugged his mother.

Hank Aaron, the coolest, most understated, least flashy baseball star of his era, desperately needed a release from the worry that his family would be harmed, from the pressure of climbing to the pinnacle of his sport while the whole world watched, from the anxiety that came with knowing failure would have helped racists feel validated, from the media, from the fans, perhaps even from himself. He needed to regain the competitive serenity that had guided him to this moment.

He needed to feel secure again. He needed his mama. And that meant my hero was not a demigod, not a media whore, not a bronze statue for the pigeons to decorate, and certainly not the “noble Negro” that some African-American theorists say inhabit white liberals’ minds.

Hank Aaron was human just like me. And that just made me worship him all the more.

— Gina K. Logue (gina.logue@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST