Upon first sight, one might feel intimidated by the 6-foot-4-inch man with 11 tattoos and booming voice, but anyone who speaks to Middle Tennessee State University senior Brian Maxwell will quickly be at ease. His smile and positive attitude are contagious around campus, and anyone who has met him once will likely remember who he is long afterward.

“The first time I encountered Brian Maxwell was at a distance. I heard him before I met him. I thought to myself, ‘This will be interesting,’ and I certainly wasn’t disappointed,” Media Arts lecturer Leland Gregory explained, recalling the first time he heard Maxwell’s voice, even though the student had been seated in the backrow of his Scripts for Media class.

Gregory served as Maxwell’s thesis director, working with him on his honors thesis — the theme of which is naked honesty, including his traumatic childhood, his brother’s accident, his time in jail, and the other things most people hide away. Gregory describes Maxwell as a deeply honest, complicated and compassionate man. “But that doesn’t really explain who he is. I can define Brian in one word: Brian.”

Maxwell, a video and film production major is an Honors Buchanan Transfer Fellow, 43-year-old married father of three who has maintained a 4.0 GPA. His oldest son, Mike, just began his freshman year at MTSU in Fall 2023. Unfortunately, the outgoing family man hasn’t always led the model life. In 2000, he was arrested for simple possession of marijuana and would spend the following six years in and out of jail. During that time, he lost his job and struggled to get back on his feet while on probation and having a record.

Now, through research and work for his thesis project, Maxwell is giving back to current inmates in Rutherford County with hands-on training and education in audio and video equipment. This is training they would not otherwise be able to receive and is unlike any other correctional education program currently offered in the state for incarcerated individuals.

Early life, moment that changed everything

Maxwell recalled seeing “Back to the Future” in theaters when he was just 5 years old. This movie ignited his passion for film production. He recalled the lights and sounds, the larger-than-life action sequences, and the story itself.

“It was like I left the Earth for two hours,” he stated.

He graduated high school in 1998 and moved from Horn Lake, Mississippi, to Smyrna, Tennessee. He got a job working in a computer room as a book distributor. His goal after high school was to begin film school at MTSU, but life changed his plans.

Admittedly, Maxwell started smoking marijuana when he was just 16. This was the crowd he fell in with and he became a daily user. “I was never a fan of alcohol, but I loved a good party, and it helped with my depression.”

One day, he was pulled over by the police for a broken taillight and was caught with marijuana. He was arrested for simple possession.

“I was completely shocked when I was arrested and I initially thought the cop was messing with me,” he recalled. “The first time I spent in jail, I felt complete shame. There was a pit in my stomach. I couldn’t look up from the floor. It took less than 30 days before I was all smiles and heckling the guards for an extra sandwich. I became institutionalized very quickly.”

In and out of the system

Over the next six years, Maxwell would be in and out of jail several times. It was always a small amount of marijuana and a probation violation. He would repeatedly be arrested for possession of marijuana, fined, and sentenced with probation.

“I feel like probation is a scheme designed to send poor people to jail. I would fail a drug test or miss a high-dollar payment toward my fines, and they would issue a warrant for my arrest,” he recalled. “It was an escalating timeframe. The first violation was 30 days, the second was 60 to 90 days, and the third was 90 to 364 days. The longest stretches I did at one time were 180 days and 145 days.”

“I was terrified the first time, nervous the second time, and felt like a veteran of the system by the third. I honestly don’t even remember the person I was before my time in jail, and I was confident that I would go to my grave institutionalized,” he explained.

Maxwell would spend his 21st birthday behind bars at the Rutherford County Correctional Work Center. Sadly, his father passed away while he was incarcerated. He also incurred a $5,000 debt from a gym membership he doesn’t remember signing up for and was ultimately sued by the gym. He couldn’t go to court because he was incarcerated at the time. It took him approximately seven years to pay it off.

In 2006, he was finally cleared of all his charges.

“After years of wasting away, I had finally beaten the system,” he said. “The air smelled cleaner, food tasted better, and a massive weight was lifted off me mentally.”

Motivation for change

After his final release, Maxwell started working in construction and any day labor gigs he could find. He worked as much as he could, sometimes earning less than minimum wage, until he broke two vertebras in his spine on a construction site.

Initially he was homeless. When he was in between trips to jail, he stayed with his brother. This would be where he would meet his wife, who happened to live in the same neighborhood at the time.

“I struggled to find work for about six months because I could no longer lift anything. I was in tremendous pain for about a decade,” he said. He was fortunate to find a desk job at a storage facility. “When the Affordable Care Act happened, I was finally able to get surgery on my fractured back. I was no longer in pain and could do things I thought I would never do again.”

After his surgery, he decided to finally start his dream of attending film school at MTSU.

“(My incarceration) was a horrible experience in the moment, but in reflection, I don’t think I would be as giving and empathetic if not for my time spent in jail,” he pondered.

His college journey began with the Reconnect Grant and Motlow State Community College, where he was also an honors student. After completing his associate degree in Smyrna, he took advantage of MTSU’s Honors College Transfer Fellowship.

“If you think of it in terms of my life as it is right now, all my experiences in jail changed my life for the better. If I had not been homeless after being released from a jail stay, I would not have met my wife. Without the stories of my experience, I would not have been given the Transfer Fellowship from MTSU,” added Maxwell.

Now, his oldest son, Mike, who is also majoring in video and film production with minors in mass communication and honors at MTSU. He started with dual-enrollment courses during high school and was able to participate in an Honors Visiting Artist’s Seminar with his father prior to starting his freshman year at the university.

Maxwell has two other sons, Keith, 15, and Kevin, 14. Both have autism. Kevin is nonverbal and suffers from a severe developmental disability, which means he will likely rely on his mother and father for the rest of their lives.

“I never had a support system until I had my family, and I am vividly aware of how important it has been to my success,” Maxwell said.

He is an avid volunteer. He has helped at Able’s Special Needs Recreation, Adam’s Place retirement home, The Waterford retirement home, and several local libraries for children’s book readings, in addition to his work at the Rutherford County Correctional Work Center. He has also raised thousands of dollars in donations for Autism Speaks.

“You will never reform criminals by sending them to jail. All you do is normalize the experience for them while making them more efficient criminals at the same time,” Maxwell said. “Instead of being in situations where they can learn a skill or take a parenting class, inmates are instead offered 20 hours a day in their cell with a few hours to waste playing card games in a slightly bigger room. You must educate and uplift to reform a person.”

Moving forward with RCCWC

Steven Sprick Schuster, an economics and finance professor at MTSU, co-authored a research paper with MTSU criminal justice professor Ben Stickle that was published in January 2023. It addresses the statistics behind the effects of education on recidivism rates.

Sprick Schuster said one of the things they found when conducting research was that education appears to have a large effect on decreasing technical violations. This suggests education may not always totally transform someone, but it may make parolees more likely to be able to navigate the system after they are released.

Education develops a lot of soft skills. Sprick Schuster said we underestimate how often people on parole get into trouble because they miss a meeting and court dates because they are bad at managing responsibilities and obligations in what is certainly a stressful situation.

Maxwell concurs based on his own personal experiences.

“I have read at a college level since middle school, and I am extremely organized. Despite all that, I found it incredibly difficult to navigate the courts, probation office, and court cost fees. Many of my return trips to jail were due to this exact situation.”

The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, known as the 1994 Crime Bill, disqualified incarcerated individuals from Pell Grant eligibility, according to the nonprofit Higher Education in Prison Research. In 2015, a pilot program was launched to restart Pell eligibility in 141 correctional facilities nationwide, which has increased to more than 200, according to the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization about U.S. criminal justice system.

At the time that Maxwell was incarcerated, attending college and using the Pell Grant to help fund it would not have been an option. In fact, the only program available to him at the time he was incarcerated was a GED class.

Studies find the effect on recidivism to be larger than the effect on employment. So, education is keeping people from returning to jail, even though they may not necessarily be finding jobs. Despite employment challenges, people are still finding purpose.

“I can’t even wrap my brain around how impactful college classes would have been on my life during that time,” said Maxwell. “My confidence and self-worth were at rock bottom, and I can’t think of anything that would have been more helpful than the opportunity to prove myself in the world of academics.”

While Maxwell’s thesis details his life, part of it also reflects on his passionate volunteer work at the Rutherford County Correctional Work Center, where he was once imprisoned. Now, on a weekly basis, he teaches the current inmates about video and film production, as well as soft skills they wouldn’t otherwise learn while incarcerated. Those he is currently teaching might now have a path forward if they choose to pursue it after his lessons with them are complete.

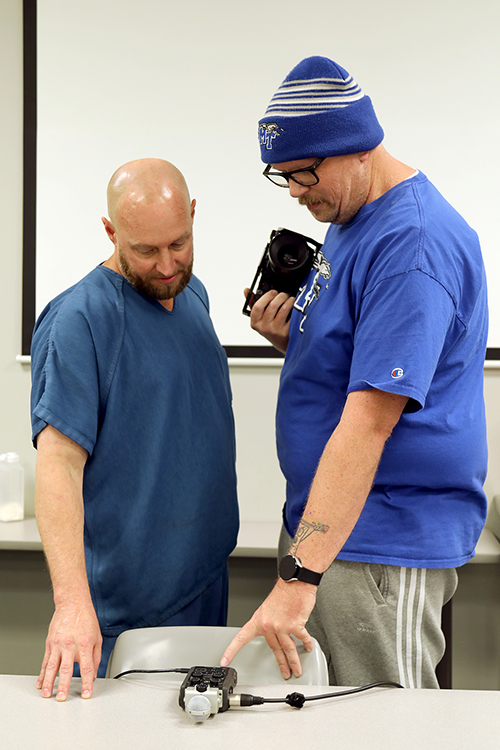

Maxwell’s unique position in this setting as an Honors College student gives him credibility with jailers and his past incarceration gives him credibility with prisoners. And he does this all with his own personal equipment. The inmates in class receive hands-on experience with audio recorders, microphones, boom poles, slates, cameras, tripods and editing software.

“I speak their language, and that is more important than any of my actual knowledge,” Maxwell explained. “I connect with them on a deeply emotional level due to our shared experiences; I want to be an example of who they can be. The situation they are in does not define who they are.”

“I think it comes down to self-respect gained thorough accomplishment. Many of these people have never found success in their life, and many others have lost whatever success they found. Getting to feel a sense of accomplishment and recognition is enough to let you know that hard work and dedication will eventually pay off,” Maxwell added.

Said Gregory, Maxwell’s thesis director and media arts instructor: “Although he can present with a rough exterior, Brian is truly a kind-hearted man. That became apparent when he told me about his work with a program he heads at the Rutherford County Correctional Work Center. I was impressed that he was donating his time, energy, and equipment, to teach prisoners how to create podcasts.

“It touched me because my girlfriend, who is a professor of English, has taught at medium security prisons, high security prisons, and even on death row, teaching prisoners the power of the written word. I am easily too big of a coward to go to most higher security prisons, especially death row.”

‘I’ll follow the breeze’

Maxwell has embraced every opportunity he has been presented at MTSU. In May, he took part in a weeklong interdisciplinary course known as the Institute of Leadership Excellence on campus. This fall, he was initiated into the Phi Kappa Phi Honor Society. He spoke at the Honors Buchanan Transfer student initiation ceremony and at the annual Honors Board of Visitors Luncheon in September.

“We had several private conversations — I was going to say ‘hushed conversations’ but that isn’t Brian’s forte. He had no problem opening up to me about his past, the good and the bad. I shared with him some of my background and more than once our pasts shared striking similarities,” said Gregory. “It’s been fun working with Brian and now I’ll be teaching his son screenwriting this fall. So, to steal the name of his thesis, I will be an honored guest at Maxwell’s House.”

After graduation, Maxwell plans to start graduate school. He said he enjoys teaching and wants to pursue a master’s degree in filmmaking. Beyond that, he wants to keep making movies with his son, Mike.

“In a perfect world, we find funding and get to make a big budget Hollywood movie. I’m more of a live-in-the-moment and take-it-as-it-comes guy, so if the winds blow right, I’ll follow the breeze.”

Adding, with a smile, “I find love, admiration and success in everything I do now. I am a pillar of my community. I want everyone who feels like they are considered less than to see themselves as equal players in this game of life. I want everyone to know the happiness I do.”

— Robin E. Lee (Robin.E.Lee@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST