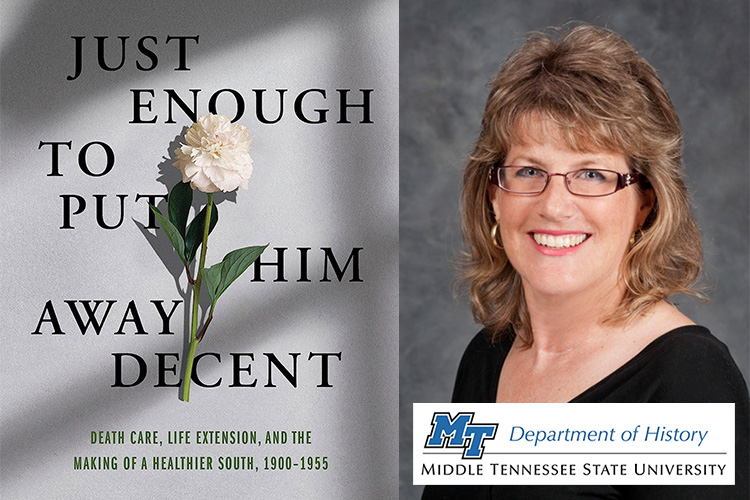

Middle Tennessee State University history professor Kristine M. McCusker chronicles how scientific advancement and biblical duties collide in her latest book, “Just Enough to Put Him Away Decent: Death Care, Life Extension and the Making of a Healthier South, 1900-1955.”

A Department of History professor whose expertise is in ethnomusicology, McCusker is interested in ways cultural behaviors affect the way people think and act. When the San Francisco, California, native moved to Murfreesboro in 2000, cemeteries were a notable trend that caught her eye with memorials ranging from elaborate monuments to front-yard tombstones.

“Southerners had definite views about death and dying,” McCusker said. “It’s visually very obvious.”

McCusker also became keenly aware how death and dying began to change in the 20th century as the South began to see a “massive drop” in mortality rates. She knew there was more to the story than just science, so she garnered a $122,000 grant through the National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine to study the cultural connections to why and how.

The magnitude of low mortality rates wasn’t fully realized until the federal government began creating death registration areas, which required funeral directors and doctors to issue certificates stating causes of death.

“Counting those causes and realizing what was killing Americans allowed health workers to begin attacking specific causes of death,” McCusker said.

In 1909 philanthropist John D. Rockefeller invested $1 million in the South to rid the region of hookworm disease, which heavily contributed to illnesses that spread easily through poor sanitation.

As public health began to improve, so did other conditions related to poor sanitation.

Health care also became intertwined with religion.

“Social, cultural, economic and political practices fed into scientific discoveries,” McCusker said. “Theological changes were so significant, that both Methodists and Baptists started building hospitals.”

But as death rates declined, expressing grief became more acceptable because death was rarer. Archives have preserved some of the artifacts that translated into heartfelt stories McCusker retells in the book, some with tearful ends.

“There are some really charming stories,” McCusker said.

She stumbled upon a school superintendent in Virginia who kept a scrapbook of his wife’s death, which included flowers, poetry and a collection of sympathy notes. The ledgers of a Black Memphis funeral home director showed sales of purple coffins fit for royalty for his Black clientele. And then there’s the collection of Mother’s Day cards sent from a World War II veteran whose fellow soldier died in a crash he survived.

Many of thes stories end up in the book; others also translate to the classroom experience.

“There is really no line between what we do to write books and what we do to teach students about history,” McCusker said.

“As I’m doing research, I’m inviting students into my world. It’s not about me teaching them what to think, but teaching them how to think about history … and engage them in a way that they say, ‘History is not boring, it’s actually fun.’”

“Just Enough to Put Him Away Decent: Death Care, Life Extension and the Making of a Healthier South, 1900-1955” is available for purchase through the University of Illinois Press and other major book retailers.

— Nancy DeGennaro (Nancy.DeGennaro@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST