Becky Seipelt-Thiemann spends some of her downtime away from her work at MTSU learning to play the cello. Daughter Laurel plays the stringed instrument at Central Magnet School, and they have split a private lesson time weekly for three years.

“I like learning new things and it’s a pretty instrument, too,” Seipelt-Thiemann, an MTSU biology professor now in her 21st year, said of the lessons, which moved from in-person to virtual like her classes in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Learning new things is what has driven Seipelt-Thiemann, who lives in Smyrna, Tennessee, for as long as she can remember. At an early age, she gravitated toward STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), particularly biology.

The Ripley, Ohio, native pursued biology at Berea College in Kentucky, graduating cum laude. Her “learning new things” interests spread to medical microbiology and immunology, earning her doctorate from the University of Kentucky. Then came new postdoctoral studies in hematology for a year at the University of Cincinnati and biological study of the genetics of yeast for two years at UK.

Seipelt-Thiemann joined the MTSU College of Basic and Applied Sciences biology faculty in fall 2000, with her quest for learning and research intact and new passion for teaching college-age students. Teaching recognitions and awards, many involving technology, soon came her way. In recent years, her expertise has helped lead to research grants totaling more than $501,000 with the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

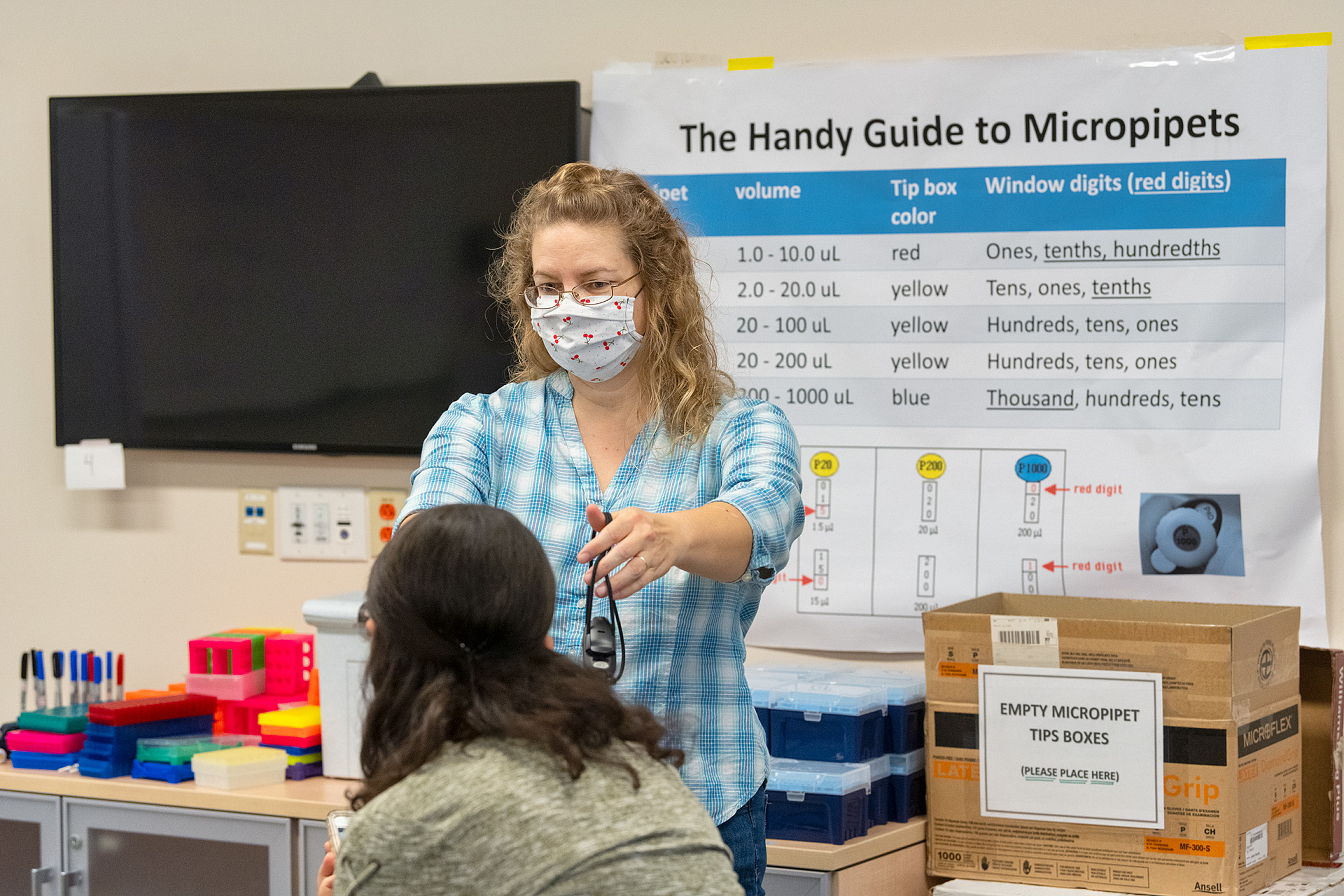

Rebecca Seipelt-Thiemann teaching her Honors Genetics class in the Science Building.

A pandemic’s impact

Seipelt-Thiemann and the rest of the MTSU faculty and students saw the spring 2020 semester interrupted by coronavirus as spring break arrived. In-person learning ceased; remote learning began. Impacted were her human genetics class, undergraduate research and genetics lab — about 230 students, including one Honors student defending her thesis and four other conducting thesis research.

It affected students’ stress levels and hers as well.

“It has been very stressful,” she said. “I felt like I was a brand new teacher again. There are things I’ve learned that I’ll continue to use, but it has been rough. … It was rough on students. I was trying to pay attention to their stress levels. I had to remove and reorganize some things during the semester, which I really hate to do.”

And it carried into the fall semester, where she taught 12 hours of classes, more than 100 students, three Honors students defending and a fourth researching their thesis; and she also was a genetics lab coordinator for 270 students that involved “a ton of work,” she said.

“I’ve learned so many new (technology) things,” said Seipelt-Thiemann, mentioning Zoom breakout rooms, Desmos, electronic grading, online course organization, scanning to PDF using her phone and more (with learning curves). She “adapted to other things I already do, making more professional recordings and ‘off-the-cuff’ recordings for collaborative work.”

For the fall semester, she said she “spent much of the summer trying to plan and organize classes along the online organization. There was so much available it was truly overwhelming. I had to step back and really look at what I thought would be useful with how I already teach (mostly flipped classroom).”

Seipelt-Thiemann’s flipped classroom is where students watch short videos she has created before coming to class. She “sells” it by asking them “to watch and learn basics at home by yourself, then we work together in class on the harder concepts and problems so that I and your peers can be there to help you if you get stuck.”

Seipelt-Thiemann said her students “adapted fairly well, but some didn’t at all. Just like me, they were learning all these new things, but have different classes and teachers that probably used different methods.” Many students remained both in her in-person and virtual classes. She incorporated video notes into the mix and less formal walk-through videos for some activities and protocols.

“I had graded daily activities that students worked on both individually and in a team of three to four,” she said. “I spoke with every student team every day of class just to check on them. They could still work with their team in class (in person) or in a Zoom breakout room. The personal connection to both their team and to me helped them stay motivated.”

With communication being a two-way street, Seipelt-Thiemann found students’ “tons of email in addition to (an online) discussion board … so overwhelming.” She added communication was “the most time-consuming part for a course where I’m lab coordinator for 11 sections of 24 students.” Students in other faculty members’ classes vented their frustrations and expected immediate responses.

Rebecca Seipelt-Thiemann teaching her Honors Genetics class in the Science Building.

A brighter 2021

By the spring 2021 semester, most of her students had adjusted to the COVID-driven situation in her bioinformatics and human genetics classes and what she observed as coordinator for the nearly 220-student genetics lab.

“Most of my students are upper classmen. In the fall, most were sophomores,” she said. “They have had the experiences (from previous semesters) and are getting used to how it’s working.”

Seipelt-Thiemann has adapted “to using the tools (technology) and I don’t have to think about how to do things now. It’s much smoother now. Students get a lot from being in-person. It will be nice when we are all able to get back together again.”

As for the cello lessons, it’s a diversion from work she will continue to look forward to, virtually — or eventually — in-person.

—Randy Weiler (Randy.Weiler@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST