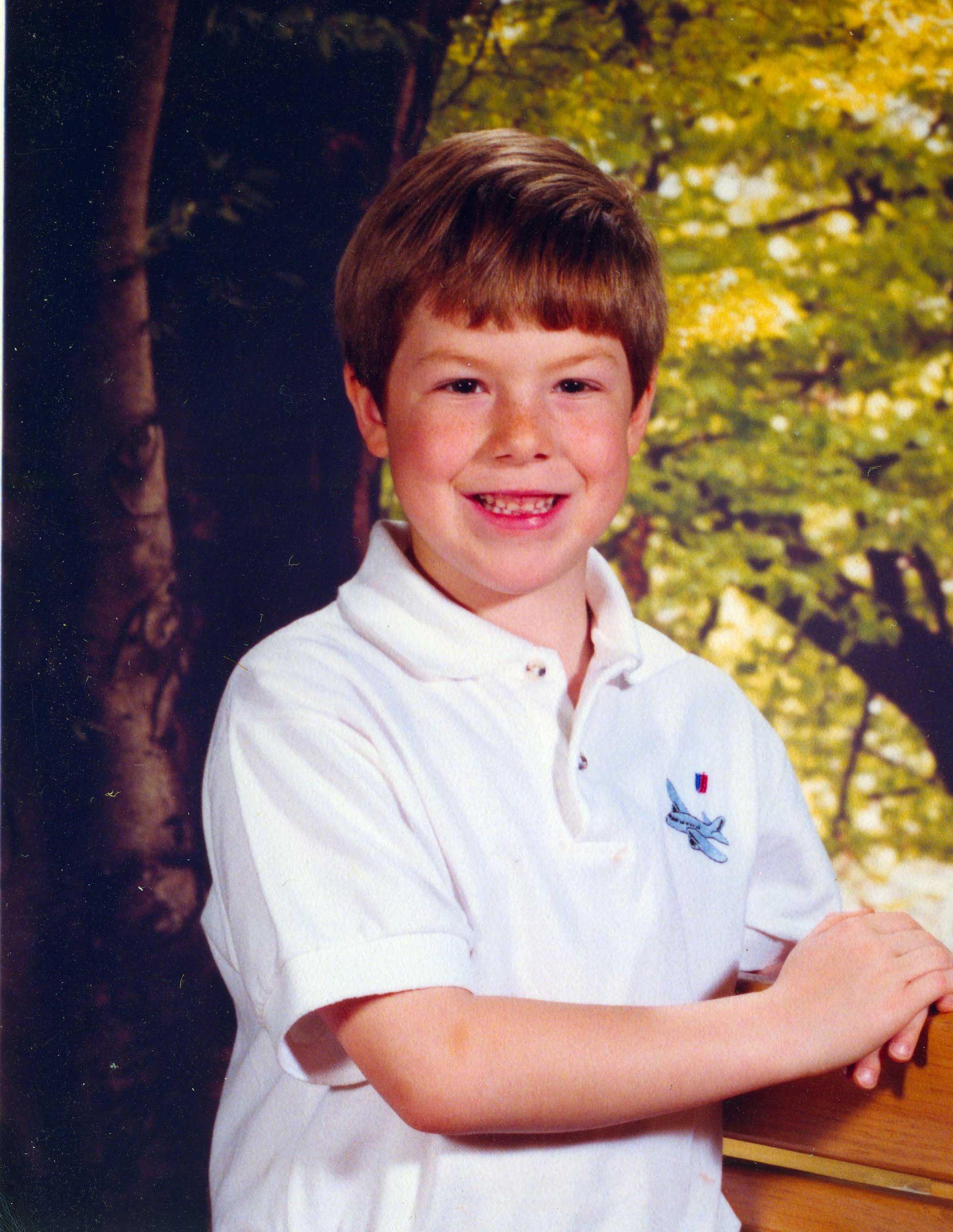

Dylan Smith was a brother and son, an uncle and grandson. He was a companion and loved. He was smart, funny and athletic. He also dealt with personal struggles caused by a mental illness. Dylan died on Oct. 2, 2022, from an accidental drug overdose. He was 29-years-old.

“There was enough fentanyl in his body to have killed six-and-a-half people,” said his mother, Liz Smith, an associate professor and director of the dietetics program at Middle Tennessee State University.

Heartbroken over the devastating loss of her son, Liz decided to focus part of her grief on sharing the circumstances surrounding Dylan’s death as a way to educate others about drug addiction while leading an on-campus effort to train others how to use naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, a nasal spray or injectable medication used to treat a narcotic overdose in an emergency.

Liz said Dylan used drugs as a way to self-medicate against a mental disorder he was diagnosed with as a young child. But she wants the world to know there’s more to Dylan’s story than his addiction and untimely death.

Bipolar diagnosis, medication

Liz and her husband, Mark, adopted Dylan as a newborn in Florida after experiencing infertility. They later had two biological children, including a son eight months after they brought Dylan home.

“We talked to the lawyer on a Thursday, thinking it would be at least six months before we had a baby. On Monday of the next week, we got a call that a mother who was eight months pregnant had come in, and we were the first ones on the list. We really believe it was a God thing,” Liz said.

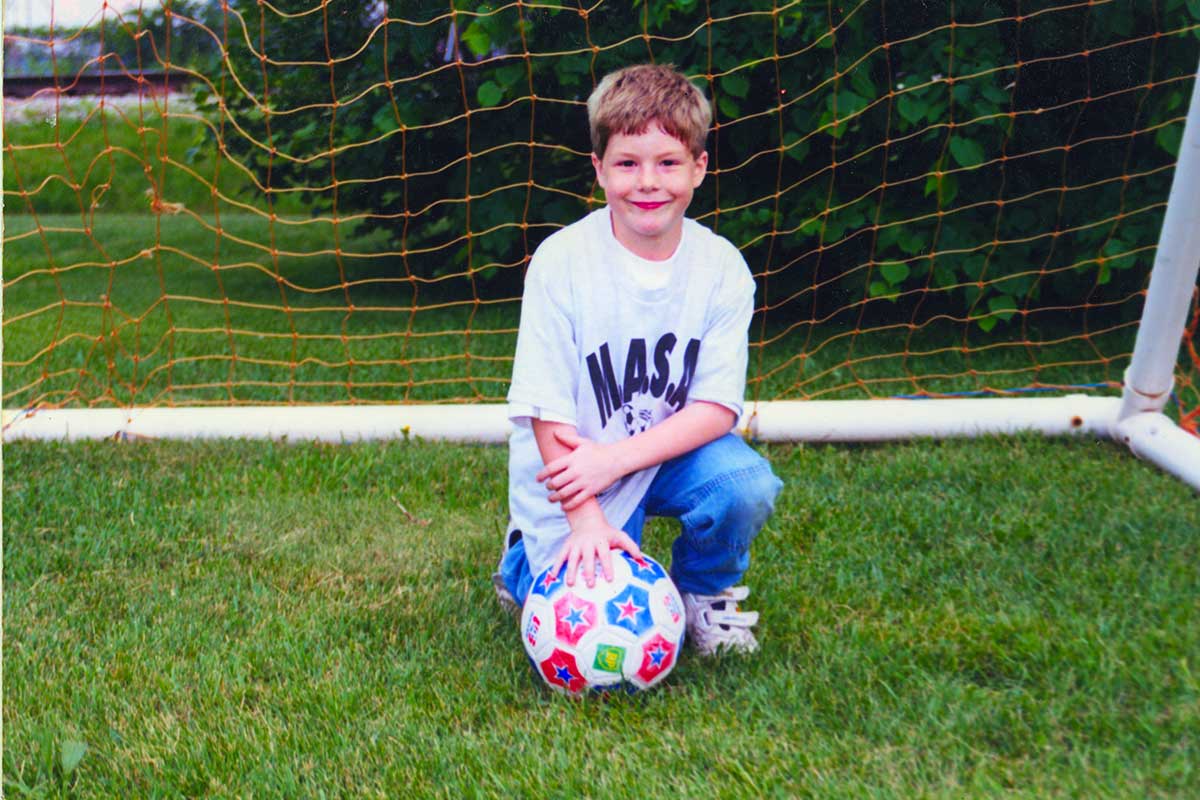

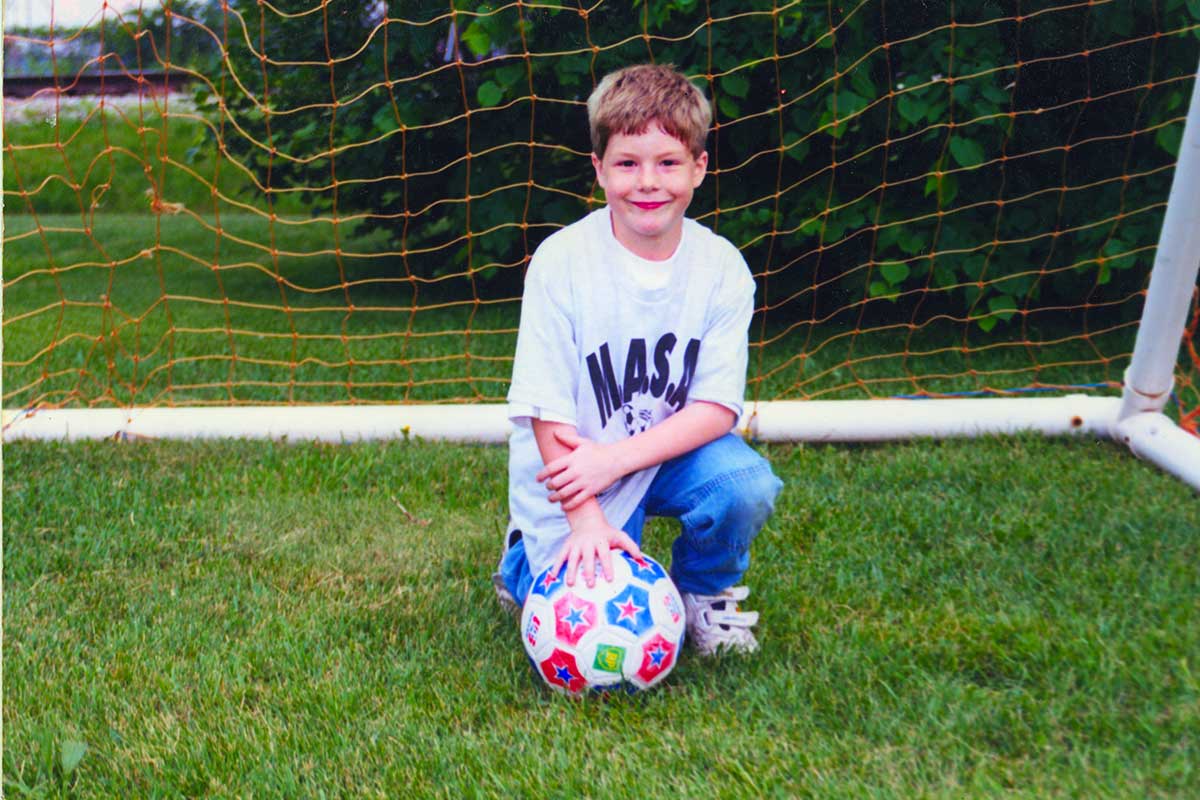

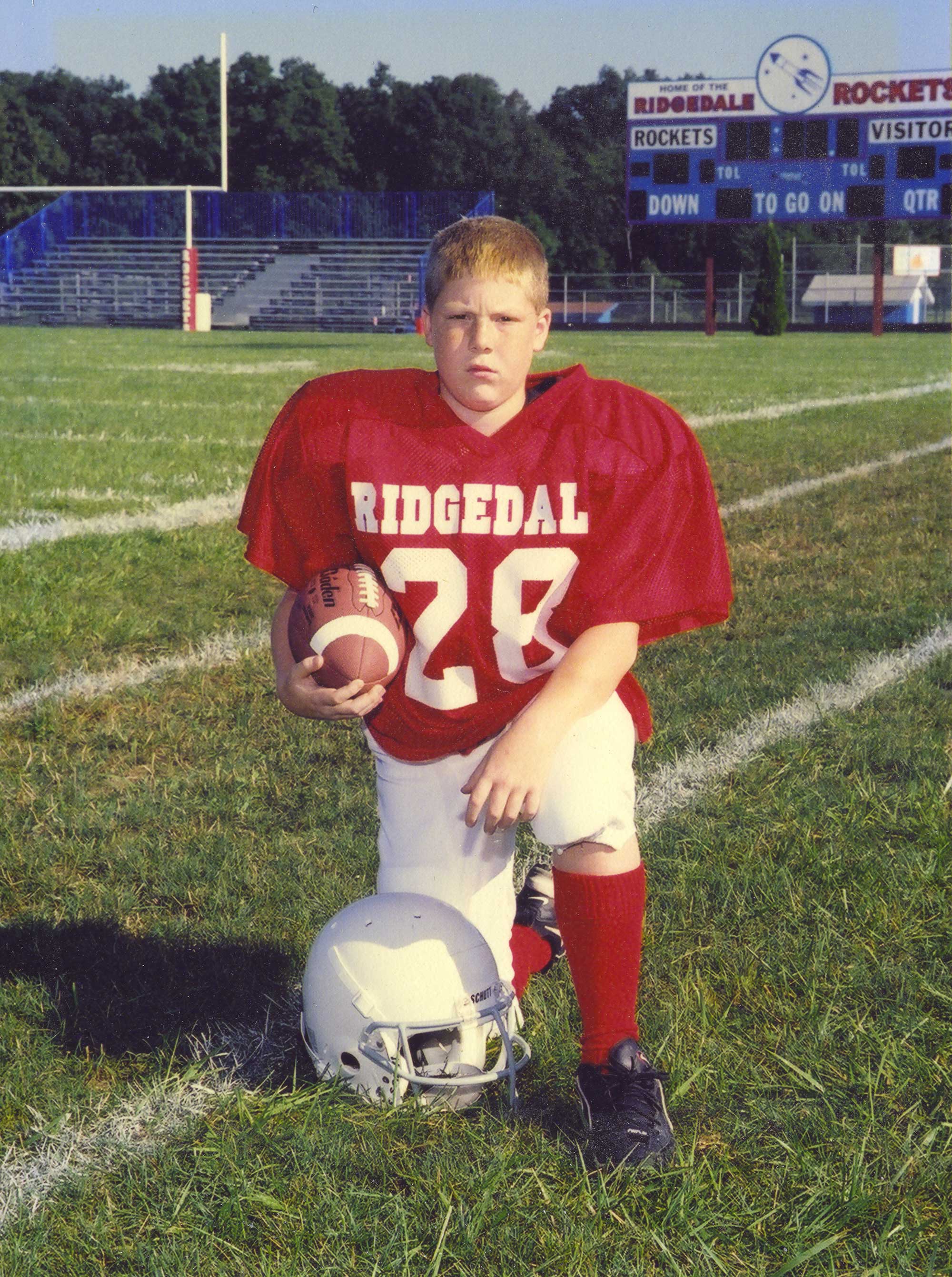

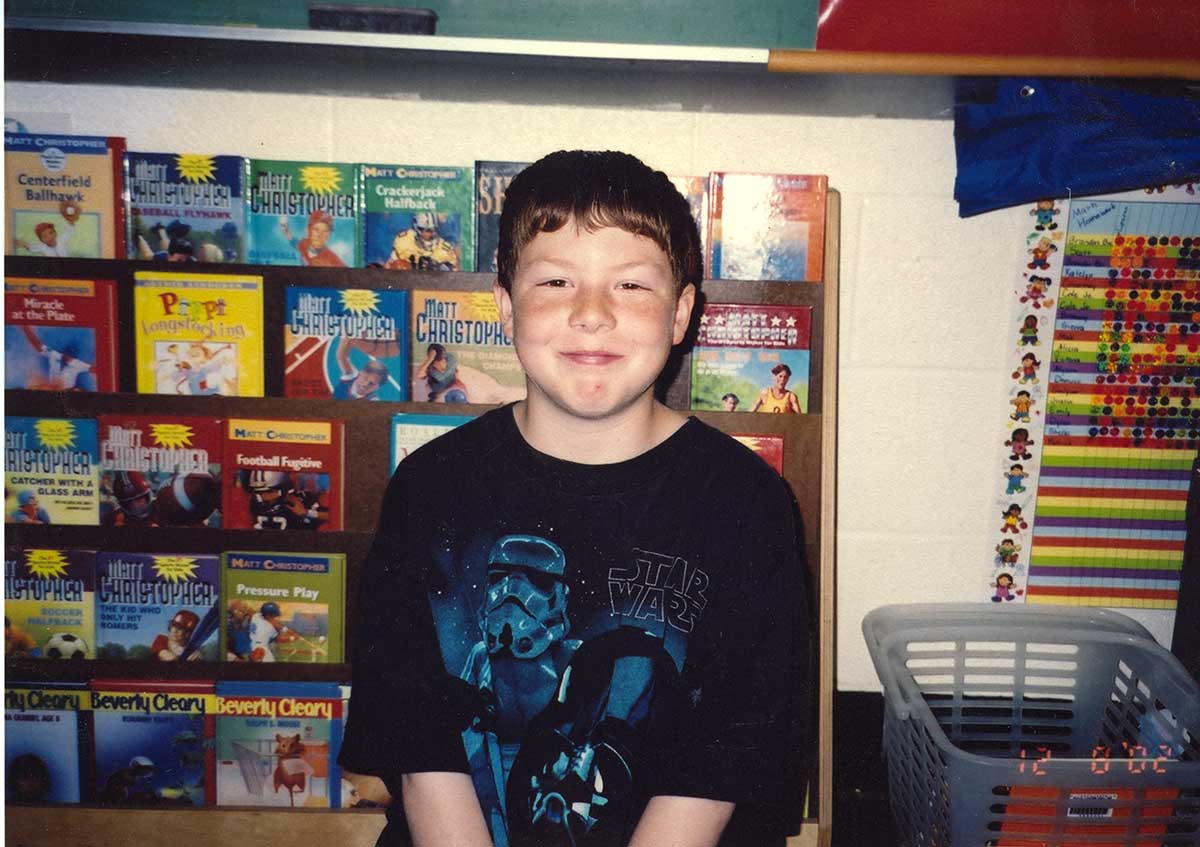

Growing up, Liz described Dylan as “all boy” who thrived at sports, was extremely bright and stubborn.

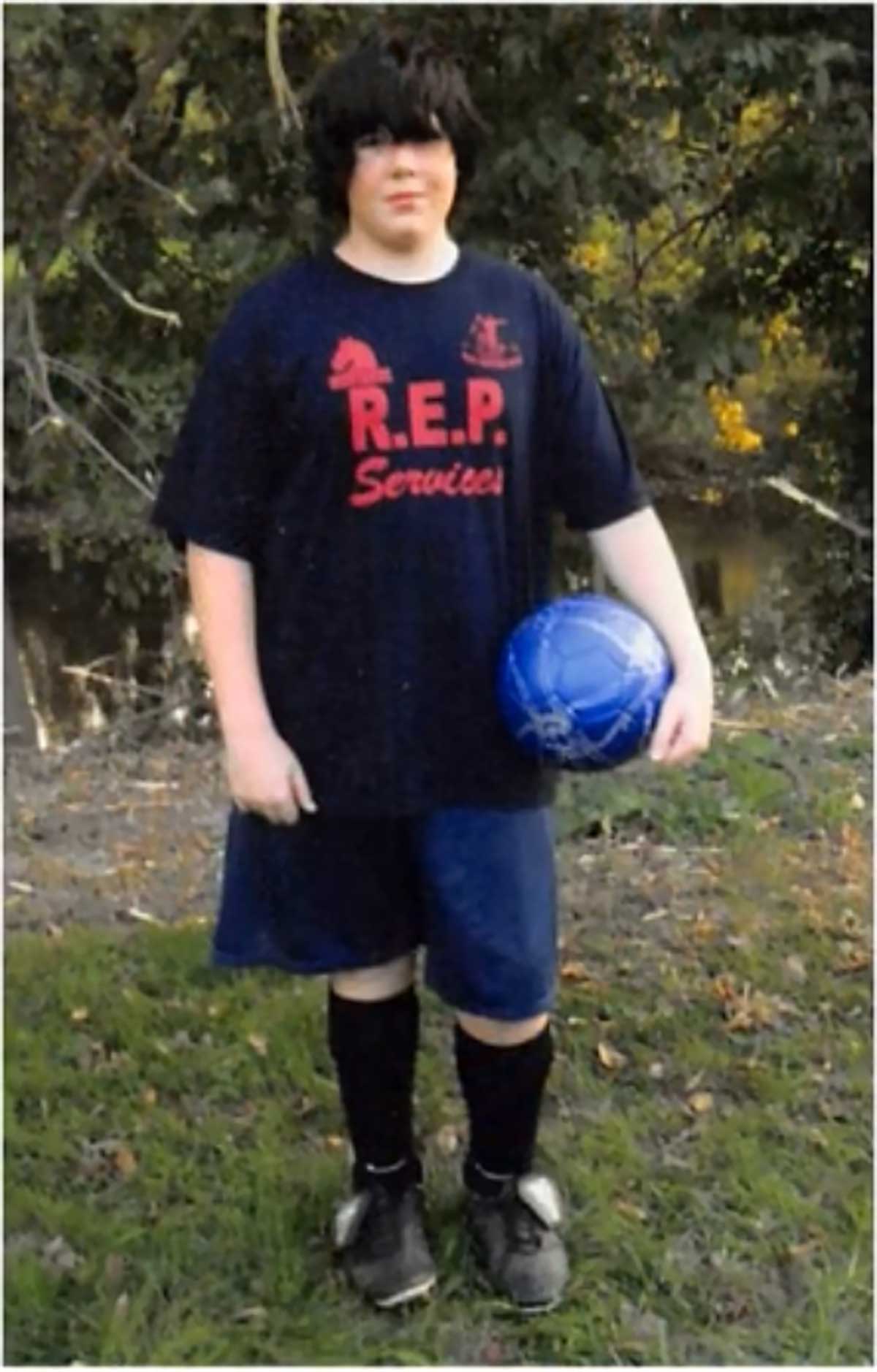

“He was always the best soccer player on the team. He was a really good teammate, and people loved playing with him. He was just really talented. He was very intuitive, very logical, and things just came easy to him,” she said.

But when he was around 10 years old, Dylan was diagnosed as bipolar.

“We started noticing things fairly young, but we thought he was just all boy. We didn’t really give it a second thought. Then he started having some different behavior issues than what you would expect,” Liz recalled.

After receiving the diagnosis, Dylan worked with doctors to get his medication right and spent some time at a residential facility in Utah.

“They found a medication that seemed to help him the most, and things went fairly well for a while,” she said.

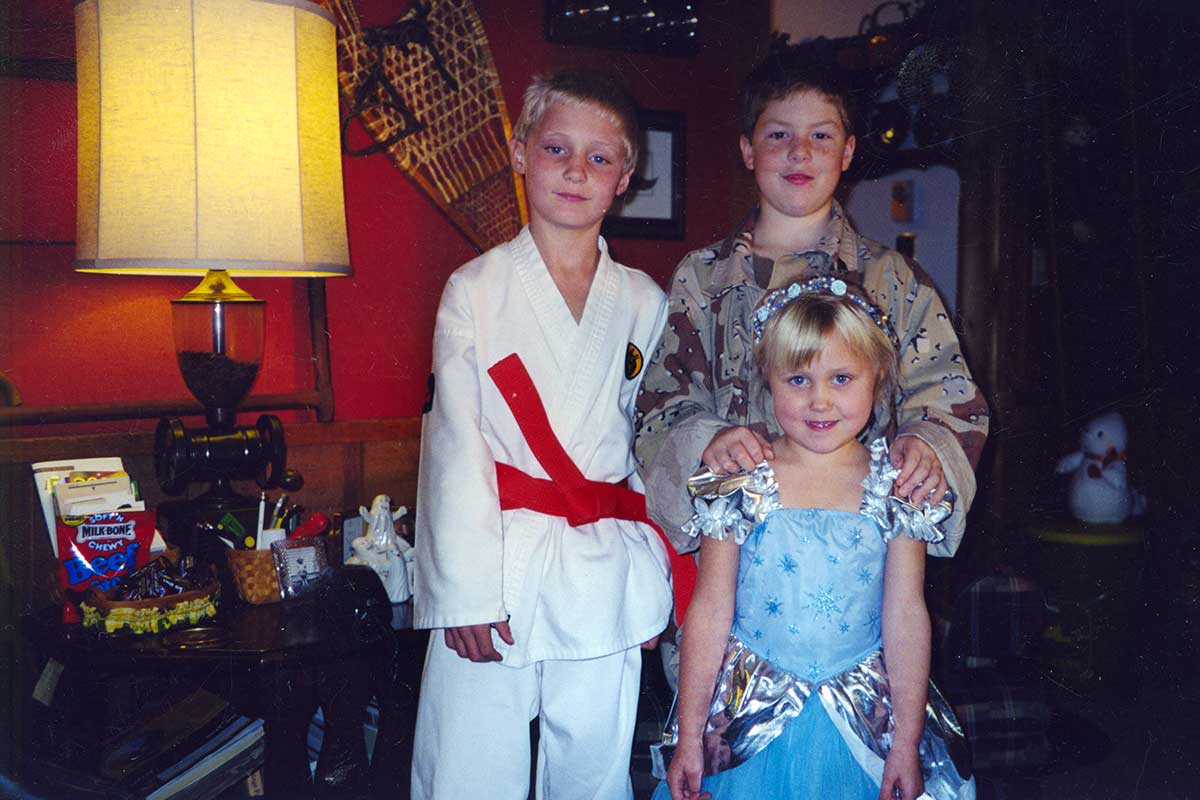

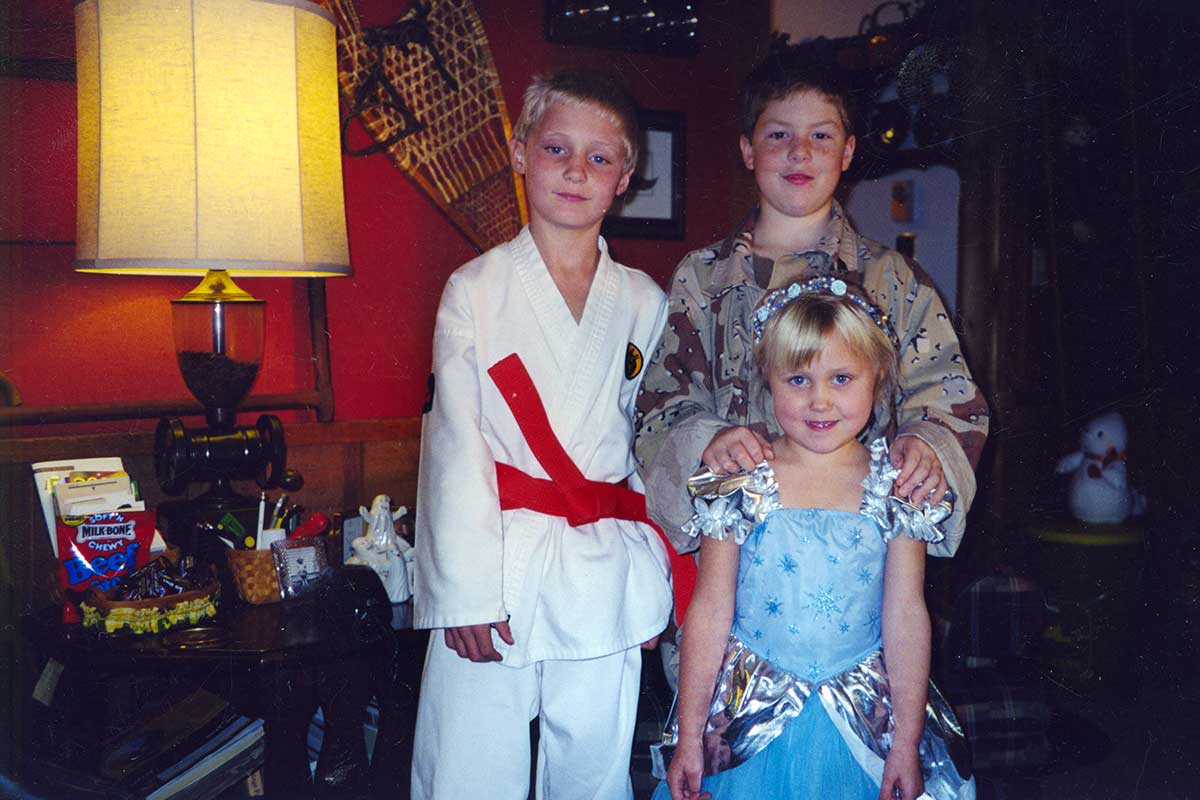

Dylan continued playing sports throughout school, did his schoolwork and stayed close to his brother and sister.

“Dylan and his brother, Tyler, did everything together, and he was very protective of Katelyn. No one was going to hurt his little sister. They always had a good relationship; they laughed a lot and had a lot of fun,” Liz recalled.

But as he got older, things began to shift, and it became a struggle to get Dylan to take his medicine, especially during his high school years.

“You could see him leveling out. But to him, that didn’t seem normal. He told us the minute he turned 18, he would not take his medicine and would leave home. He left the day after he turned 18, and he never took his medications again.”

From 18 to 29 years old, Dylan self-medicated. He first began using marijuana and later Adderall and methamphetamine.

“Those were the primary drugs he used, and that’s what was in his toxicology report,” Liz said.

In the 11 years he was actively using, Dylan went to rehab four times.

“We were always really hopeful, but he would always walk out after a few days,” Liz said. “The last thing I texted him is that he needed to go to a long-term rehab. I wanted him to do that so that he would still be here. I think my husband and I always knew we would get that call (if he didn’t get clean).”

Before his death, Liz said Dylan had a second interview scheduled at an Ohio fast-food restaurant.

“He had plans for the future. He was so excited to be offered $13 per hour. He had plans to purchase a car in the future.”

Educating, training others

In the summer of 2023, months after losing Dylan, Liz knew her son’s story could make a difference. She began organizing trainings on naloxone, a nasal spray commonly known as Narcan, on MTSU’s campus with the administration’s support, including Amy Aldridge Sanford, vice provost for academic programs.

“Amy is the most supportive person I think I’ve ever worked with at this administrative level. She’s wonderful, very open-minded, very caring and very willing to listen. I knew she was the right person to go to,” Liz said.

Aldridge Sanford said when she heard Liz’s story, she immediately supported educating as many people as possible on campus and the community about Narcan and how it can save a person’s life.

“She’s heartbroken over the loss of her son, and it did not surprise me that an educator would want to educate as their activism. She wants to create systemic change; she wants to go out and make sure that we minimize the possibility of this ever happening again,” Aldridge Sanford said.

Since June 2023, Liz has held around a dozen training sessions and helped educate around 400 people on Narcan with the help of the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

“Her passion is unbelievable. Unless you’ve been through it, you can’t be that kind of messenger. She’s so brave,” Aldridge Sanford said. “She wants to save lives. As a college educator, she knows education can do that.”

The trainings, which lasts around an hour, includes Liz telling her son’s story and overdose prevention specialist Brittany Laborde going through the steps on how to administer Narcan, what happens when a person overdoses and how Narcan works.

Laborde says it’s important to stay with the person when they are experiencing an overdose until emergency medical services arrive.

“Naloxone very rarely has any negative side effects if administered when there are no opioids involved. When in doubt, administer naloxone if it is available,” she said. “If an individual is experiencing an opioid overdose, naloxone will temporarily restore breathing, lasting 30 to 90 minutes, and cause the individual to experience symptoms of withdrawal.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, fentanyl is the No. 1 killer of people 18 to 45 years old.

“A deadly dose of fentanyl can be as small as 2 milligrams,” explained Laborde.

The Tennessee Department of Health reports that in 2021, there were 3,814 fatal overdoses in Tennessee, which was a 26% increase from 2020. According to Laborde, in 2021, almost 3 in 4 overdose deaths in Tennessee involved fentanyl.

Tennessee, like many other states, has a Good Samaritan Act, which provides protection for people or agencies who administer Narcan in good faith to a person who is believed to be experiencing an overdose. The state also has the Tennessee Addiction Treatment Act that allows the use of Narcan and provides some legal protection for the person who calls for medical attention and the person experiencing the overdose.

“Just don’t take the chance. Don’t take anything unless it’s through your pharmacy. You can’t trust it,” Liz said. “If I can save one person, I feel like I am at least helping.”

If you or your organization is interested in having Liz host a training, please contact her at Elizabeth.Ann.Smith@mtsu.edu.

— DeAnn Hays (DeAnn.Hays@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST