Long-lost history does not have to stay lost, as long as people are willing to work together to pinpoint the past. “Places, Perspectives: African American Community-building in Tennessee, 1860–1920” is an ongoing project that combines the resources and expertise of James E. Walker Library with help from the Department of Geosciences, MTSU’s Center for Historic Preservation (CHP), and a dedicated group of community historians.

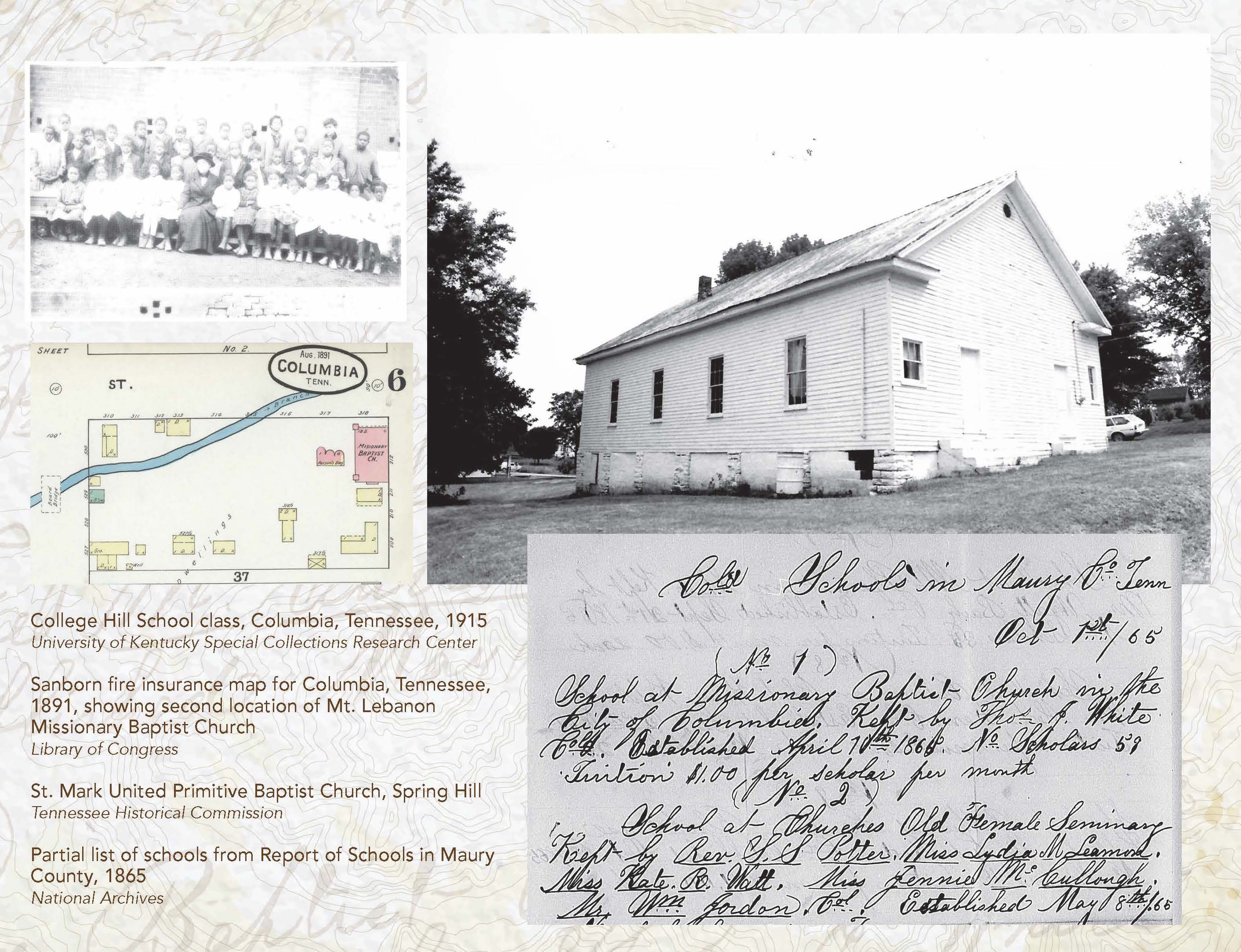

After the Civil War, freed African Americans “quickly sought to create new physical spaces that belonged to them and reflected their values,” according to CHP Director Carroll Van West, who has documented buildings and sites across the state that bear witness to the formation of communities. “Besides homes for their families, they rushed to create three institutions in particular: churches, cemeteries, and schools.” The church, surrounded by homes and businesses, was usually the focal point and often doubled as the school building.

Using West’s summary as a guiding principle, the “Places, Perspectives” pilot project is finding, researching, and mapping clusters of African American churches, cemeteries, and schools in four sample counties. These counties—Greene, Maury, Fayette, and Hardeman—represent the geography and demography of Tennessee from east to west.

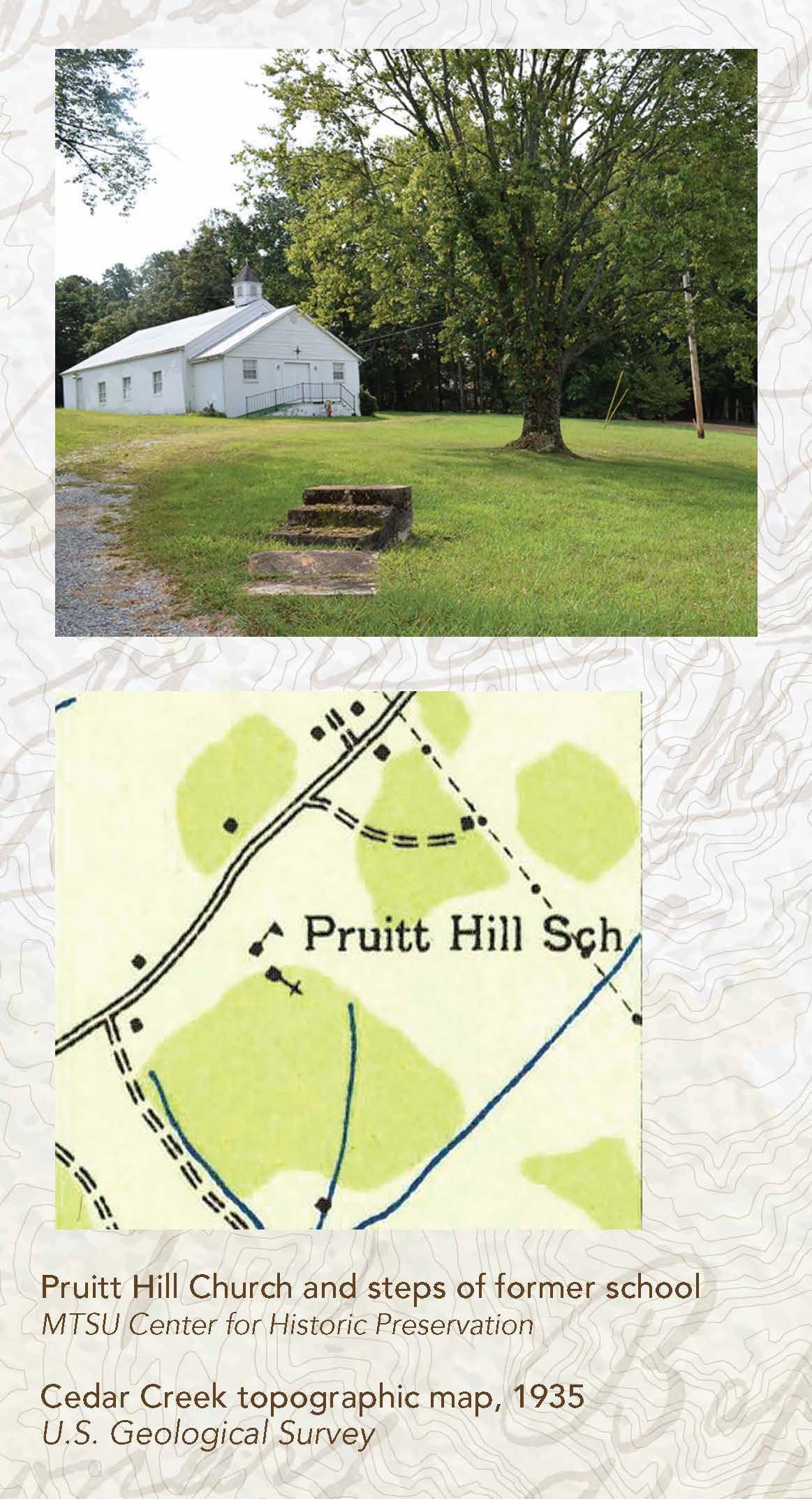

Archaeologist Zada Law, director of MTSU Geosciences’ Fullerton Laboratory for Spatial Technology, uses geographic information system (GIS) technology to link historic data to places on the ground.

“We have mapped and documented 115 of these communities and more than 450 actual properties,” said Ken Middleton, MTSU digital initiatives librarian. Properties pinpointed on a map link to evidence of their location or history through 400 digitized primary sources already available in the “Places, Perspectives” companion digital collection (digital.mtsu.edu/digital/collection/p15838coll17).

“My interest is in elevating the cultural landscape of African American geography,” Law said. “I’m particularly interested in archaeological sites and recognizing them in cultural resource management studies.”

Susan Knowles, a digital humanities research fellow at the Center for Historic Preservation, said historic maps, particularly from the Civil War period, have been highly beneficial.

Because Tennessee was occupied early,” Knowles said, “there are a lot of great Civil War-era maps where we were finding things that matched up with, say, newspaper advertisements for mustering of the Colored Troops in Tennessee.

Jo Ann McClellan, the Maury County historian, provided “boots on the ground” experience in the area in which she lives. McClellan is trying to establish an African American museum and cultural center there, and the work she has done on this project puts her closer to realizing that goal.

“This is just going to be game-changing for the African American community once we establish this facility,” McClellan said. “I’m thinking that once we have this museum, we will use this information as a base for some of the exhibits. It’s going to open a lot of eyes, both in the Black and white communities.”

In east Tennessee’s Greene County, Law, Middleton, and Knowles rented an 18-passenger van for a day out with older residents who shared memories at sites like Pruitt Hill and Chuckey and met with local family historians during a stop at the Bulls Gap Railroad Museum.

Project participant Dravidi Pasha, a senior Information Systems major whose mother’s side of the family hailed from Fayette County in west Tennessee, appreciates the value of obtaining information from his oldest surviving relatives. His advice for budding genealogists is clear.

“Appreciate and enjoy your elders and . . . interview your elders about their past experiences, their knowledge of the past, and their wisdom,” Pasha said.

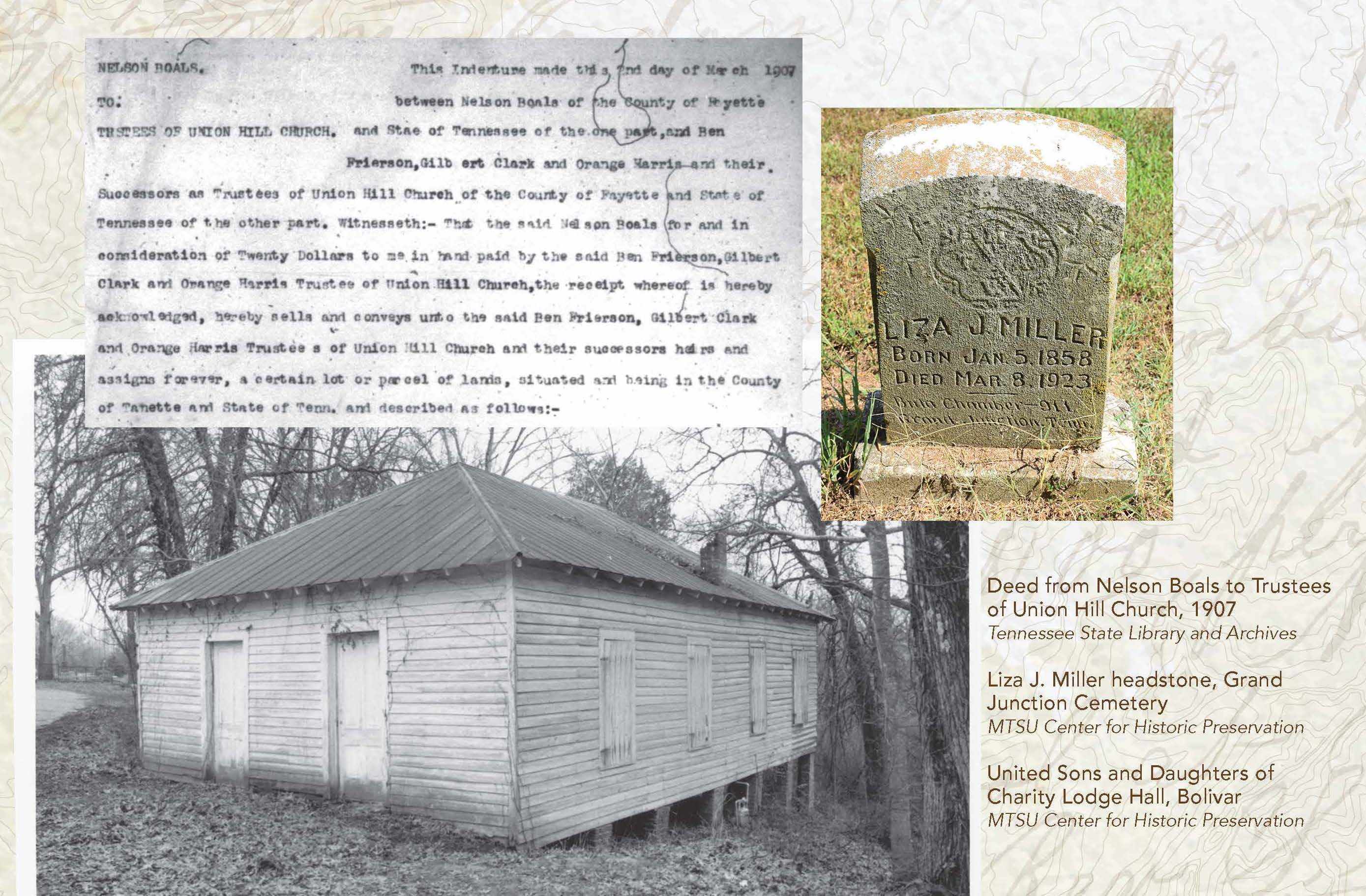

Pasha, who had already been researching his family history, was generous with his knowledge and eager to find confirmation of what he had learned. One ancestor in particular, a former enslaved worker named Nelson Bowles (sometimes spelled Boals), impressed him.

“Upon the Union soldiers’ coming to raid the plantations and release the slaves, he actually joined the Civil War,” Pasha said. “He was enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops 59th Infantry Regiment, and I believe it was Company D.”

The project turned up a deed showing Boals sold land in 1907 for the Union Hill Church in Gallaway and a record from 1878 where a woman of color, Susan Broomfield, deeded the same church its first location, Knowles added.

One of McClellan’s favorite discoveries in Maury County was the story of Edmund Kelly, born into slavery in Columbia, Tennessee, who gave candy to boys at a school where he was working so that he could learn from them how to read.

In 1843, Kelly co-founded and became the first pastor of the Mt. Lebanon Missionary Baptist Church in Columbia before leaving for a pastorate in Massachusetts in 1855. With a delegation of other African American ministers, Kelly met with President Abraham Lincon in 1863 to gain permission to minister to escaped slaves who had fled to the North. His son, John, returned to Columbia in the early 1870s and became an influential educator.

The project continues, a labor of love for a dedicated group concerned with education, preservation, history, and social justice.

We’re trying to be transparent in the way we map locations and cite our sources,” Law said. “We’re trying to think about the future. We want this to be a sustainable project. We want it to be a model that other people can build on.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST