MTSU’s resident vampire expert explains the ongoing societal fascination with the undead

by Kayla Bates

Whether people are drawn to vampires because they are mysterious, or symbolize power and sexuality, or even because they evade death, the popularity of their stories doesn’t seem to be slowing down. With True Blood, Twilight, Vampire Diaries, and novel after novel about these undead creatures cropping up in bookstores, we’re unlikely to see them disappear anytime soon.

Whether people are drawn to vampires because they are mysterious, or symbolize power and sexuality, or even because they evade death, the popularity of their stories doesn’t seem to be slowing down. With True Blood, Twilight, Vampire Diaries, and novel after novel about these undead creatures cropping up in bookstores, we’re unlikely to see them disappear anytime soon.

Stories of vampires reach back before written language. Dr. Jimmie Cain, MTSU professor and Bram Stoker scholar, says the archetype of a creature that dies and comes back to life stems from people falling into cataleptic states—a condition characterized by a trance or seizure, with a loss of sensation and consciousness accompanied by rigidity of the body. Today, we call these states comas.

“In the past, people didn’t know,” Cain says. “They thought when you fell into a coma that you were dead. Vampires probably come from stories of people that they thought were dead, were buried, and then found around town in their burial gowns, covered in blood because they had to dig their way out of a grave.”

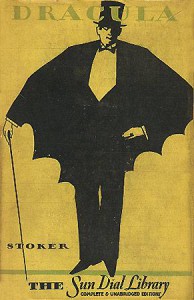

The vampire story that roused modern-day public interest is the ever-famous Dracula, published at the end of the 19th century and written by Stoker. But Stoker may be rolling over in his grave about what has happened to the vampire tale in modern culture.

“Bram Stoker, if he were alive today, would be horrified to see that we have True Blood, that valorizes vampires, and Twilight, where we have a vampire hero,” says Dr. Cain. “For Stoker, the vampire was a distillation of every conceivable form of evil imaginable: religious, spiritual, domestic, sexual, and I’d argue political evil, as well.”

By comparison, Edward Cullen is more inclined toward true love rather than true blood. Modern interpretations clearly highlight more humanistic qualities in vampires than do the older tales.

By comparison, Edward Cullen is more inclined toward true love rather than true blood. Modern interpretations clearly highlight more humanistic qualities in vampires than do the older tales.

Cain says this trend toward warmer, fuzzier vampires actually has its roots in the 1970s and movies featuring actors like George Hamilton playing a debonair, sophisticated vampire.

“I think it’s a reflection of counterculture,” Cain says, “of people turning away from traditional values. They see in the vampire the real rebel.”

Another theme recurrent in vampire stories that has morphed over time is the liberation of women. In the Dracula story, the women who are turned to vampires immediately become sexual.

“These turned women lose all the demeanor and probity of a proper Victorian woman and suddenly become sexually rapacious,” Cain says.

While we don’t see Bella Swan instantly changed into a woman hunting for sexual experiences, Stephanie Meyer, author of the Twilight saga, does portray the newly vamped Bella as a wickedly beautiful, almost eerily perfect physical manifestation of a woman. The concept of beauty and eternal youth clearly resonates in a modern society seemingly obsessed with staying young.

Cain speculates that in addition to our desire to remain young and beautiful forever, the rise in popularity in vampire stories could be linked to the increasing number of people who have lost their belief in an afterlife.

“If there’s no heaven, maybe the next best thing is to live forever,” says Cain.

But based on the way vampires grow restless and lonely, wishing for the true death granted to humans, it’s difficult to idolize an eternity on Earth.

What hasn’t changed, regardless of era, is the public’s appetite for a good vampire tale. Though the themes have changed, and our collective reasons for enjoying them, vampire tales are most definitely here to stay.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST