article by Allison Gorman and photos by J. Intintoli

Beth Salem Presbyterian Church is now easy to find. You take the Riceville exit off I-75, just north of Cleveland in east Tennessee, and follow your GPS across and around gentle hills to a flatter area between Athens and Etowah, in McMinn County. On Arbin Watson Road, you’ll pass modest ranch houses separated by fields, then you round a bend and there it is. Closer to the road than the houses were.

It’s not the church itself that’s striking, although the church is the first thing you see. Its lines are so simple (clearly there’s a single room inside) and its coloring so stark (whitewashed weatherboard, plain white front door, white shutters over the windows on both sides) that it stands out against the grass and trees.

What’s striking is the feeling of community even though there’s no one there—unless you count the folks in the graveyard across the road. A few yards away from the church, off to the side, there’s an outdoor kitchen. A respectable distance behind the church, and from each other, sit two sturdy outhouses, doors ajar.

Beth Salem sits there waiting 364 days a year. It’s rewarded at homecoming, the fourth Sunday of August. Every year since 1955, families have gathered at the church from as close as Athens and Etowah, and as far away as Cleveland, Sweetwater, and Loudon, to celebrate a community and a sanctuary.

They also came home to keep the church from falling apart, said Ann Hitchcock Boyd, who still lives close by. A descendant of one of the founding families, she was 5 years old that first homecoming; now she’s 73. The folks who gather there from far away seem to be getting fewer, she said.

Boyd tends to the church herself much of the year. Her parents and her brother Bennie used to tend it too, before they joined the older generations across the road. The younger generations are busy with living.

What the church represents, and the responsibility to preserve it, weighs heavily on Boyd. The place is tangible evidence of a story that’s been mostly told, not written.

“That was the piece of history that I could walk through,” she said. “I can walk into that church and know that I had ancestors that walked into that church, that had religious services at that church, that walked on those grounds. And you know, sometimes I can feel that presence when I’m there. I can walk over to the cemetery, look at some of the markers, and feel like that’s home.”

THE PLACE IS TANGIBLE EVIDENCE OF A STORY THAT’S BEEN MOSTLY TOLD, NOT WRITTEN.

The Written History

There are three markers in front of Beth Salem Church.

One marker, erected in 1999 by the National Register of Historic Places, designates it as the first African American congregation established in the region of Polk, McMinn, and Meigs counties.

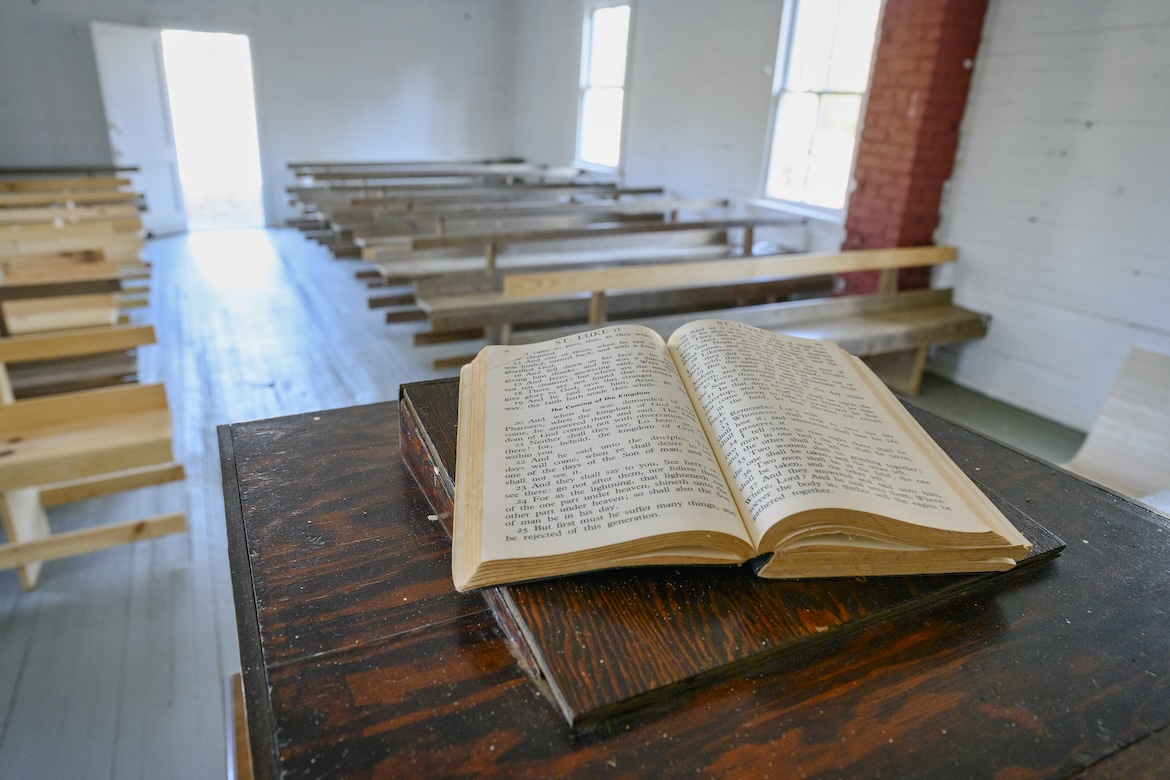

The church was organized in 1866. Its members, newly freed and illiterate by design, initially met under a brush arbor, then built a log church on donated land. The original log structure, which also served as a school, was destroyed by fire in 1920. Friends and neighbors pitched in to build a new church. That’s the shuttered one that stands today.

A third marker, from 2020, tells a little more about the unincorporated area known as Beth Salem.

Another marker, erected in 1928, is a monument to the congregation’s original trustees and its founders: the Rev. George Waterhouse and the Rev. Jake Armstrong, two Black ministers; the Rev. Fate Sloop, the white Presbyterian missionary who helped them; and Martha Patsy Fite, the white woman who donated the land.

Once an integrated community of subsistence farmers, it hollowed out as folks left for industrial and service jobs. According to the marker, regular church services ended there in the early 1950s. Boyd thought it was earlier. Either way, it marked the end of a long decline.

“When the railroad and things came to Athens and Etowah, young men didn’t have to farm anymore, and they went to work in the factories,” she said. “So they quit having church in the church altogether. That’s when it fell into disrepair.”

The marker includes a black-and-white photo of little Ann in Sunday clothes, standing with her family near the church in 1955. She doesn’t remember that first homecoming, she said. But she sure remembers the ones after that, because she got to dress up and eat dinner outside.

“There was no running water, but there was a big spring down at the bottom of the hill,” Boyd said. “I always thought it was fascinating to use a dipper to have a sip of spring water.”

One of the best parts of homecoming was getting to see friends they hadn’t seen in a year.

“It was one of the few Sundays that my dad would get excited about going to church,” she recalled with a chuckle. “He didn’t get excited about going to our local church in Etowah. But when it was time to go to homecoming at Beth Salem, he’d make sure there was plenty of food in the car and we left home early.”

Her dad loved homecoming even though he didn’t grow up in Beth Salem, she added. These were her mom’s people.

Over the decades, the stories Boyd heard from her mom’s people became as fascinating to her as that dipper of spring water. Some were fluid, as oral histories tend to be.

BY THE LATE 1990S, THE CHURCH WAS STARTING TO SHOW ITS AGE . . . PEOPLE AND MEMORIES WERE TRICKLING AWAY.

The Oral History

As Boyd understands it, her great-great-grandmother Sylvia was born into slavery in South Carolina. Near the end of the Civil War, she and her three children were separated, sold to different farms in the McMinn County area in Tennessee. When the war ended and Sylvia was freed, she went in search of her sons and her daughter, Daphne, traveling from farm to farm in a rickety mule-drawn wagon.

When Daphne saw Sylvia drive up, she hadn’t seen her mom in two years.

According to the story Boyd shared with the Black Christian News, 15-year-old Daphne “jumped into the wagon without looking back. Years later, she told family members that even if she lived to be 1,000 years old, she would never forget the day that her mother came to get her.”

To Boyd, she’s Grandma Daphne, her mom’s mom and the family historian. Boyd’s mom passed away more than 20 years ago, and of course Daphne’s been gone longer than that—her resting place across the road from the church.

There are few people left who can give a firsthand account of Beth Salem when it was a thriving community with a vibrant church at its center. One of them is Hettie Dickey.

Dickey remembers how women would gather at the church on Saturdays to stuff ticking after the men had harvested the hay. Changing the mattress straw was part of spring cleaning.

“The hay back then wasn’t as hard as it is now because they had different machinery,” Dickey said. “They used horses and had different machines. It wasn’t like this motor stuff. We got everything motorized now.”

She and her twin sister were 2 years old when their father died, leaving their mother with seven children to raise. Their mom later told them he died of pneumonia after he began catching rides to work in the back of an open truck.

Dickey still remembers how she and her siblings would run out to the road to meet him when they’d see him walking home from his job in Athens.

“We would always run to meet him, and he would always have some candy. That’s the only thing I remember—except I remember his funeral. Somebody picked me up to view his body. I still remember that. But that’s all.”

At 87, Dickey remembers going to regular church services at Beth Salem. She laughs when she remembers her Sunday-school teachers, widowed sisters named Mary and Mandy, bickering with the preacher, Walter Dotson.

But there’s nobody left to remember the earlier days when Beth Salem was not just a church but a school.

By the time Dickey was old enough for school, there were Rosenwald Schools all over the South, including rural east Tennessee, so Black children could get a formal education (see sidebar below, “A Fuller Picture”).

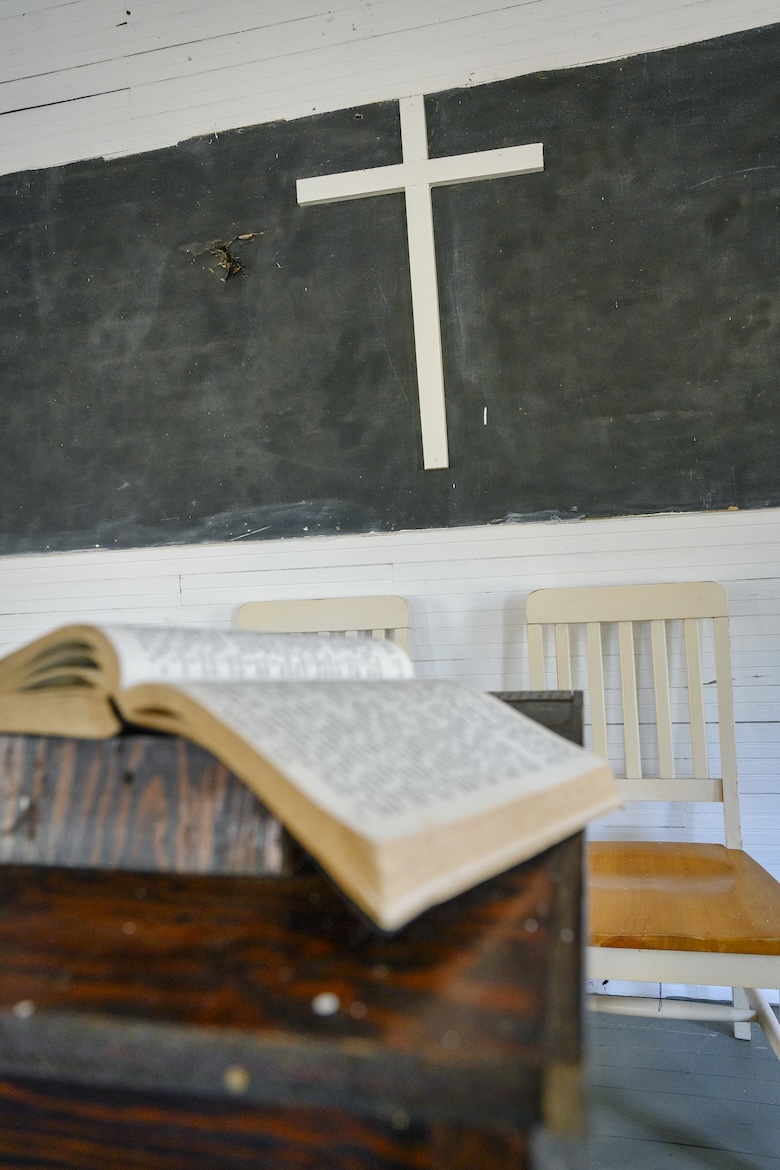

The only thing left in Beth Salem Church from those earlier days is the homemade chalkboard behind the pulpit. It hangs high on the wall, and there’s a bullet hole in it. The shot came from outside. Nobody remembers what happened.

By the late 1990s, the church was starting to show its age, and Boyd was getting worried. People and memories were trickling away, but the church was still solid. She wanted to keep it that way.

The Power of Preservation

What Boyd remembers most about MTSU History Professor Carroll Van West when he visited Beth Salem is that he was very excited about the outhouses.

“I do find privies to be important,” said West, who is also the Tennessee state historian. “So she is not the first person to laugh at me about it.”

As the longtime director of MTSU’s Center for Historic Preservation (CHP), West visits important but often overlooked historic sites across Tennessee and the United States—documenting what’s left to preserve and then developing a preservation plan, usually for free.

When Boyd contacted West, he’d just written a book, Tennessee’s New Deal Landscape, about President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s public works projects in the Volunteer State. One project was the installation of tens of thousands of modern outhouses—around 3,700 in Cleveland alone, he said. The project didn’t just give rural people meaningful employment; it also improved public health.

THOSE DIFFERENT BUILDINGS, PLAIN AS THEY ARE, WITH THE SETTING AND THE CEMETERY, REALLY DEFINE . . . A COMMUNITY AND PLACE.

Most New Deal privies are long gone. Discovering two of them behind Beth Salem Church was a rare treat.

But what really captivated West as a historian was the wholeness of the scene he saw. Church, kitchen, privies, graveyard.

“Those different buildings, plain as they are, with the setting and the cemetery, really define a community and a community place,” he said.

“Those are really invaluable locations throughout our country, where you can see that here’s a place people gather and share.”

Preserving the sense of place has always been the focus of the CHP—preserving its elements, however humble, so the place can tell the stories when the people no longer can.

Beth Salem tells the unique story of an integrated Southern community that was at its most vibrant during the most volatile era in the American South, save the Civil War itself. Reconstruction and Jim Crow were uniquely dangerous times for Black people in Tennessee, home of the Klan.

“When you look at Beth Salem, it’s the place that really captures your eye,” West said. “It’s off on a secondary road; it would have been a bit hard to find. But that was probably smart for the Black families back during the Jim Crow period, to be out of sight. You know—out of sight, out of mind.”

Oddly enough, that was a little easier for Black people to do in very white, rural east Tennessee.

“The number of African Americans was never, in so much of that region, very large; therefore, they were never perceived as a particular threat,” West said. “That’s very different than in other parts of the state.”

As far as Dickey knows, her family was not affected by racial turmoil. In fact, some of the people who helped her mom after her dad died were white.

“We were safe,” she said. “They were good, nice people. Really, when segregation and all that came up, it didn’t affect us because we were used to them. We were neighbors.”

One thing everyone knows for sure is that Beth Salem was special.

West got the church nominated for the National Register of Historic Places in 1999, in time for Boyd’s mom to see it.

“Thank God she saw that before she passed away,” Boyd said. “That was a wonderful day, to see that letter.”

The National Register preserves the history of the place. Whoever owns the place has to preserve what’s on it. Boyd wasn’t sure who owned the church, but as more years went by and the floor and ceiling started sagging, she decided she had to save it.

That’s the latest unwritten chapter of the Beth Salem story.

What Boyd remembers next about working with West is how thorough he was: measuring, photo-graphing, documenting things in need of repair, crawling under the church’s sagging foundation.

And that was just for the Historic Register nomination.

In 2017, at Boyd’s request, West developed a preservation plan. Since then, she’s raised some funds and gotten some important work done. The church has new paint inside and new whitewash outside. There are new pews to match the old ones, and new glass in the old windows. Fixing all the sagging things will be the bulk of the expense. Boyd figures it will take at least $70,000 to do that. She’s working on a grant.

In 2022, Boyd discovered who owns Beth Salem. Its last living trustee signed the deed over to the Hiwassee Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. They didn’t know they owned it either, but when Boyd told them, they were glad to hear it. She was relieved to learn that Beth Salem is in bigger hands than hers. Because it isn’t just a building.

“One thing Beth Salem gives us is community artifacts,” she said. “That church is an artifact. That cemetery is an artifact.”

They’re artifacts of a history that goes as far back as memories go.

A Fuller Picture

Beth Salem Church was always more than a spiritual sanctuary for its African American congregation. It was their social hub, and for its first decades, it was their school.

After that, but before desegregation, many Black children in the rural South, including east Tennessee, went to Rosenwald Schools. Funded in part by philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, 5,000 of the schools were built in the South between 1917 and 1932 to give Black children a state-of-the-art education.

In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Places put the Rosenwald Schools on its 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list.

There were two Rosenwald Schools in Etowah, where Ann Hitchcock Boyd and her mother were raised. By the time Boyd started school in 1955, it was no longer a Rosenwald School—it had been remodeled. And she didn’t go there long. But what she recalls about it lines up with how her mother used to describe the two-room schoolhouse.

The memories came flooding back when a friend told her about the Dunbar Rosenwald School in nearby Loudon. He’d gone to school there, and it was still intact. Some people were trying to preserve it.

Boyd, who’d been working with MTSU’s Carroll Van West to preserve Beth Salem, offered this advice: “Well, the first thing you need to do is get it approved as a 501(c)(3). Then get Dr. West to do a preservation study.” They took it.

With plenty of elbow grease, a solid preservation plan, three grants Boyd won, and support from the Loudon community, they were halfway through renovations in 2023. Just in time to celebrate the little school’s centennial anniversary.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST