Despite working toward equality at the ballot box, in the courts and as citizens since the nation was born, panelists at an MTSU Constitution Day discussion agreed that in this women’s suffrage centennial year, Americans still aren’t equal.

From racial injustice to voter suppression to literal concrete examples of white supremacy, speakers at the “Voting Access, Equity, Justice: Beyond Celebration” panel Sept. 17 pointed out that Black women have laid the groundwork and pushed hard for change across American society, only to see their efforts co-opted and overshadowed — and worse, ignored and denigrated — by white men and women.

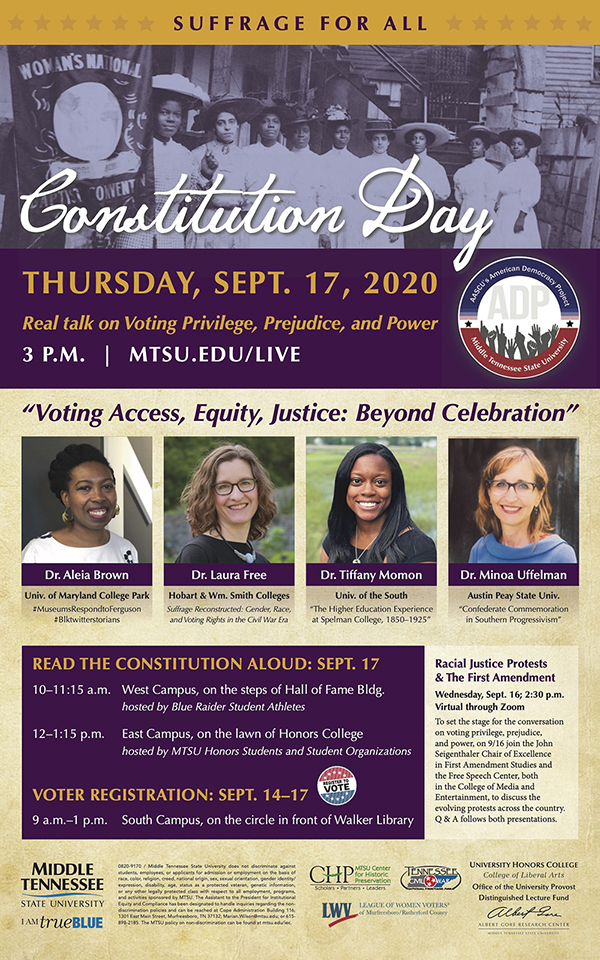

Participants in MTSU’s Sept. 17 Constitution Day panel, “Voting Access, Equity, Justice: Beyond Celebration,” discuss the setbacks and challenges faced by Black women working toward passage of the 19th Amendment and the aftermath of that work. Clockwise from upper left are Aleia Brown, an alumna of MTSU’s doctoral Public History Program and the assistant director of the African American Digital Humanities Initiative at the University of Maryland’s Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities; Laura Free, chair of the Department of History at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, N.Y.; Minoa Uffelman, a history professor at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tenn.; and Tiffany Momon, another MTSU public history alumna and a visiting professor of history at Sewanee: The University of the South. (MTSU photo illustration)

The complete panel discussion is available on video above.

“We’ve not fully and honestly divulged how truly racially hateful so much of the battle for suffrage was,” said Dr. Tiffany Momon, an MTSU doctoral Public History Program alumna who’s now a visiting professor of history at Sewanee: The University of the South.

Dr. Tiffany Momon

She pointed to then-Tennessee House Speaker Seth Walker’s August 1920 boast on the legislative floor, during the 19th Amendment vote debate, that “this is a white man’s country.”

“Despite the progress of the last 100 years, our cultural landscape … tells a story primarily dominated by white men, and often our historic sites … don’t reflect the diversity of this country. They certainly don’t reflect the complexity of history.

“So often these things gloss over the ugliness of history in favor of happier stories, and I think it comes as no surprise to anyone here that glossing over the ugliness of our shared past gets us nowhere.”

Dr. Laura Free

The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1868 to make former slaves full citizens, referred only to “male inhabitants” and “male citizens” — the first time gender-specific language became part of the founding document. The 15th Amendment, passed two years later, guaranteed those men’s right to vote regardless of color.

Some of the white women, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who’d been working for suffrage for all alongside Black activists like Sojourner Truth, resorted to racist stereotypes to fight these flawed laws, claiming white women were more qualified to vote than Black men.

Their actions escalated a rift already forcefully condemned by abolitionist, suffragist and author Frances Watkins Harper at the 1866 National Women’s Rights Convention.

MTSU panelist Laura Free, chair of the Department of History at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York, said Harper was one of the first to denounce what we now call structural racism.

Frances Watkins Harper

“She started calling out a wide range of racial injustices that she sees in America, and she tells people there is so much more to equality than just the ballot,” Free said of Harper, quoting the Black leader:

“You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. … We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity. … I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.”

Because of this continuing racism, Free said, she sees the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage as something she “won’t celebrate, but commemorate.”

“The 19th Amendment did not enfranchise all Americans; far from it,” she said. “We know that indigenous women did not vote in reliably safe ways … and Black women and Asian American women and Latinx women — there are so many ways that people were shut out of the ballot.

“I tend to view this year as a space for reckoning and a space for conversation and to think about the ways that we are still trying to live up to the promise of full voting rights for all Americans.”

Dr. Aleia Brown

Dr. Aleia Brown, assistant director of the African American Digital Humanities Initiative at the University of Maryland’s Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, said that Black activists’ suffrage work is only one slice of the weighty load they’ve shouldered, and continue to lift, for the nation.

“Black Lives Matter did not come out of a vacuum,” Brown, also an MTSU Public History Program alumna, said, referring to the political and social movement that began in 2013 after teenager Trayvon Martin’s killer was acquitted.

“It came out of lots of struggles, and many of the women you’ve already mentioned, the … three women who founded Black Lives Matter (Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi) definitely looked back at them and the past, and looked at how black women were organizing, and looked at the shortcomings, looked at the successes, and carried those lessons into today.

“Ferguson (Missouri) is not an isolated place,” Brown said of the city that saw extensive protests in the wake of Michael Brown’s 2014 killing by police there.

“There are many places that experience police violence, state-sanctioned violence, so in that sense Ferguson was not unique; it was more of the norm. And 2014 was not an isolated time. … Black people have been struggling for freedom and struggling to live in the United States (for centuries). 2014 was not the first time people saw an unarmed black person being gunned down.”

Dr. Minoa Uffelman

Dr. Minoa Uffelman, a history professor at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee, said changing such embedded inequities in America begins with educating every generation, every gender and every race.

“I was teaching the chapter of our textbook that spoke about when African Americans are disenfranchised by the ‘grandfather clause’ and all those other things, the literacy test, the poll tax, and the students were simply appalled,” she said. “They couldn’t believe that Americans would do that to other Americans.

“I said, ‘You know, voter suppression is happening right now … in Alabama just the other day, they made it that you had to have a driver’s license to vote and then they closed the driving centers in the counties with black populations,’ and they just couldn’t believe it. One of the students was like ‘Are you punking us?!?’ And I said no, this is really happening.

“I said, ‘You know, voter suppression is happening right now … in Alabama just the other day, they made it that you had to have a driver’s license to vote and then they closed the driving centers in the counties with black populations,’ and they just couldn’t believe it. One of the students was like ‘Are you punking us?!?’ And I said no, this is really happening.

“That’s a very basic form of education,” Uffelman continued. “We can educate our classrooms; we can educate in our conversations with students. We have to fight, as individuals, against voter suppression and have to elect officials to fight voter suppression. We have to include everybody.

“That is the theme that’s running through today: we can’t just do it for white women. Everybody has to be included.”

Dr. Karen Petersen

Dr. Karen Petersen, dean of MTSU’s College of Liberal Arts and a professor of political science, served as moderator for the online discussion, which lasted about an hour after an unexpected technical delay was resolved.

MTSU’s 2020 Constitution Day observance, organized by the campus chapter of the American Democracy Project, also featured two opportunities for public readings of the full Constitution, along with four days of open voter registration.

Monday, Oct. 5, is the deadline to register to vote in Tennessee in the Nov. 3 election. Early voting in Tennessee is set Wednesday, Oct. 14, through Thursday, Oct. 29.

For more information about the American Democracy Project at MTSU, email amerdem@mtsu.edu or visit www.mtsu.edu/amerdem. For information on voting in Tennessee, visit www.mtsu.edu/vote or https://sos.tn.gov/elections.

— Gina E. Fann (gina.fann@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST