An internationally recognized expert in forensic science builds a powerhouse program at MTSU

by Allison Gorman

It was bitterly cold and growing dark -a terrible time to hunt for bones. But when Dr. Hugh Berryman got the call that a child’s skull had been found near Stones River National Battlefield, he knew he couldn’t wait for the luxury of daylight. Soon, snow would blanket what was looking like a crime scene.

It was bitterly cold and growing dark -a terrible time to hunt for bones. But when Dr. Hugh Berryman got the call that a child’s skull had been found near Stones River National Battlefield, he knew he couldn’t wait for the luxury of daylight. Soon, snow would blanket what was looking like a crime scene.

“There was no way of holding that site,” recalls Berryman, a research professor with MTSU’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. “It’s Friday night; on Monday I’m leaving town for a week; and snow is coming. I’ve got two days to make this work.” So he and Forensic Anthropology Search and Recovery (FASR) Team abandoned their weekend plans and met on site, where detectives from the Rutherford Country Sheriff’s Department (RCSD) had secured the wooded area and were waiting nearby with generators and halogen lights. “Our team were the only ones inside. We worked for hours.” Before dawn, they had collected and photographed a set of remains, later identified as a toddler who had been reported missing from her Smyrna home two years earlier.

They had done their job. They couldn’t bring the child back to life, but they could provide some answers and the possibility of justice.

RCSD Detective Ralph Mayercik, who had placed the call to Berryman, says he could have called the department’s own crime scene group, “but we probably wouldn’t have gotten that quick of a response or that level of expertise.”

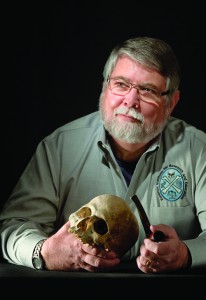

That’s not surprising, considering Berryman’s reputation as one of the nation’s foremost forensic anthropologists; Berryman recently learned that he will receive the 2012 award for lifetime achievement in physical anthropology from the American Academy for Forensic Sciences. The T. Dale Stewart Award, given annually to a single recipient, is the highest honor bestowed upon a forensic anthropologist in the United States. Venerable institutions like the Smithsonian regularly tap his expertise on bones and bone trauma. Since moving to the Nashville area in 2000, he’s made himself available to regional law enforcement and other agencies who deal with death and homicide. As MTSU Provost Brad Bartel notes, “Hugh Berryman is probably on the speed dial for a lot of counties in middle Tennessee.”

What’s more surprising is the makeup of his FASR team -all MTSU students handpicked by Hugh Berryman, and many of them undergraduates.

Crewing the Flagship

Since Berryman joined the MTSU faculty and established FASR in 2006, he and the team have collected and analyzed remains for local law enforcement and fire departments, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, and the State Medical Examiner’s Office in Nashville.

The TBI’s routine use of FASR as a resource indicates “a tremendous level of confidence” in the team, says TBI director and MTSU alum Mark Gwyn (’85). “You’re trusting people with other people’s lives -not only a victim but a potential perpetrator and all the ramifications that go with that down the road, such as trials and court proceedings.”

At first, that trust was anchored by the weight of Berryman’s authority. Now his FASR team is earning its own credentials.

Dr. Tanya Peres, an associate professor of anthropology whose undergraduate students assist her with lab and field work, says MTSU’s forensics and anthropology students tend to display the sort of commitment that leads to pulling a Friday all-nighter in the bitter cold. “I’ve taught at several universities,” she says, “and I’ve seen a level of dedication from our undergraduates I haven’t seen in other places.”

Certainly the glamorization of forensics has inflamed student interest across the United States. But at MTSU, Berryman has turned forensics into a flagship program that benefits students and community alike; it operates as an invaluable regional resource while turning our graduates who are several steps ahead of their competition.

Hired to bolster the quality and visibility of MTSU’s forensics program, Berryman has done so systematically, as is the nature of a forensic scientist.

He created FASR to give his students critical field experience while lending scientific expertise to regional authorities who, as Berryman says, “don’t know one bone from another.” He founded MTSU’s Forensic Institute for Research and Education (FIRE), which offers extensive training for local law enforcement. He developed MTSU’s Legends in Forensic Science Lectureship, which attracts high-profile speakers like renowned anthropologist Dr. Clyde Snow, whose testimony has helped convict perpetrators of genocide, and Dr. Kathy Reichs, crime novelist and producer of the television show Bones. (Both are Berryman’s peers on the elite American Board of Forensic Anthropologists.)

He created FASR to give his students critical field experience while lending scientific expertise to regional authorities who, as Berryman says, “don’t know one bone from another.” He founded MTSU’s Forensic Institute for Research and Education (FIRE), which offers extensive training for local law enforcement. He developed MTSU’s Legends in Forensic Science Lectureship, which attracts high-profile speakers like renowned anthropologist Dr. Clyde Snow, whose testimony has helped convict perpetrators of genocide, and Dr. Kathy Reichs, crime novelist and producer of the television show Bones. (Both are Berryman’s peers on the elite American Board of Forensic Anthropologists.)

Last fall, building on the momentum Berryman created, MTSU introduced a bachelor’s-level program in forensic science -the only one in Tennessee, one of only three in the Southeast, and expected to be one of fewer than 20 accredited programs of its kind in the country.

Bartel says this confluence of talent and opportunity in forensics will give the University national name recognition. “As a provost, you want all your programs to be as good as they can be,” Bartel says. “But some, by nature of the quality of the faculty you ahve, and maybe just the uniqueness of the program, rise to a higher level nationally. I view the forensic program as one of those signature, reputational programs for MTSU.”

Bringing the Bone-a Fides

If Berryman is the guiding star in this constellation, you wouldn’t know it by his demeanor; he is affable and absolutely without pretension, his accent belying his west Tennessee roots. He’s also quick to laugh, which almost makes one forget how gruesome his work can be -until he starts to talk about it.

In that respect, Berryman is strikingly similar to Dr. Bill Bass, the pioneering anthropologist who established UT-Knoxville’s legendary “Body Farm.” In fact, Berryman earned his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees under Bass, working as his teaching and then his research assistant. (“I know you’re not supposed to get all your degrees from one place,” Berryman says, “but I was interested in bones. I would be stepping down to go anywhere else.”) The two have been fast friends ever since.

It’s hard to say whether Bass rubbed off on Berryman or where likes attract like. But Berryman says he saw in Bass how to be a teacher and a mentor, and Bass says he recognized in Berrymant he qualities that make a great forensic scientist.

Berryman recalls his first class with Bass.

“It was such a fun lecture; he was just all over the place, and I remember leaving and thinking, ‘Man, we laughed through the whole thing; we didn’t get anything done.’ Then I realized I had seven pages of notes -and I thought, ‘That’s how you do it.'”

Bass says students learn best through humor, which also helps lighten an inherently dark subject. “Hugh is funny, he’s a great lecturer, and he’s fun to be with,” Bass says. “And if you’re going out to look at a dead body, you want somebody that’s fun to be with.”

And Hugh Berryman has looked at a lot of dead bodies. After earning his doctorate, he joined the faculty of the Department of Pathology at UT Health Science Center in Memphis and was director of the Regional Forensic Center there, overseeing the morgues for the medical examiner and UT Medical Center. he took the job so his two children would be close to their grandparents in nearby Weakley County; they stayed there 20 years, until his wife’s job took them to Nashville, where he went into private consulting. Along the way, Berryman established his reputation as the go-to guy for bone analysis -from helping identify bodies to determining the cause of bone trauma.

He has lectured at the Smithsonian Institution, which in 2005 invited him to join an elite scientific research team examining the 9,300-year-old skeleton dubbed “Kennewick Man.” He is also part of the effort to exhume the body of Meriwether Lewis to determine whether his shooting death was a suicide, as originally reported, or murder. (Despite Lewis’s descendants’ offer to pay for the investigation, it is being held up by the National Park Service because Lewis’s grave near Nashville is on federal parkland.)

Berryman also provides consultation and regular testing and review for the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory (CIL) in Hawaii, which identifies soldiers from as far back as the Civil War. It’s one of the world’s most technologically advanced forensic labs, says its director, Dr. Tom Holland, and home to a lot of professional egos. “What’s critical about having external consultants is that the analysts whose work is being looked at have to respect that reviewer,” Holland says. “If they don’t, it’s an immediate friction point. Hugh Berryman is universally respected -not only within the profession but certainly in this laboratory.”

Holland says Berryman possesses a rare and valuable combination of qualities: “He has extreme wealth of knowledge, and he knows how to use it.”

Bearing the Burden

But for the forensic scientist, that skill set sometimes must extend from the scientific and the practical to the psychological.

It’s one thing to work with bones with old, dried tissue on them,” Berryman explains. “But how do you handle someone that you’ve pulled out of a car who is burned up but not completely burned up? How do you handle a decomp where the odor is so strong, and what you’re looking at is just disgusting -this used to be a person- and there are insects and maggots?”

Eventually, he says, you get used to the smell. (He warns against using Vicks VapoRub under the nose, à la the autopsy scene in The Silence of the Lambs: “It makes you hate menthol.”) And staying focused on the task at hand helps distract from the gruesome visuals.

More difficult to block out are the details of a heinous crime, especially when it’s your job to document them. Berryman has worked on many brutal murders but admits that one, the 1985 slaying of a young woman in Memphis, still haunts him, and he can’t entirely explain why. He doesn’t like to talk about it, and even with this passing reference, his customary spark dims. “It got into my mind and I couldn’t get it out,” he says. “I don’t ever want to have another one do that. I can’t afford that.”

Regardless of academic aptitude, he concludes, some people simply can’t handle the psychological rigors of fieldwork -and the typical forensics student doesn’t get that type of exposure until graduate school, after they’ve already invested years in the classroom. That’s why Berryman created FASR, a special collaboration between university and law enforcement, to give MTSU students practical experience at the undergraduate level.

Making the Cut

Not all of Berryman’s students, and not all forensic science majors, are on the FASR team. Students may apply for one of 10 spots only after they’ve completed one of Berryman’s two forensics classes, taken coursework familiarizing them with human and animal bones, and had archeological field experience. Berryman talks to their teachers, noting which ones seem smart, diligent, and (his favorite quality) “aggressive.”

Those who make FASR are invited to accompany and assist him at crime and accident scenes. “His team has come out on several cases with me, and they’re wonderful,” says Denise Martin, lead death investigator for the State Medical Examiner’s Office and herself one of Berryman’s first students at MTSU. “They’re incredibly mature and very knowledgable.”

And maturity is critical, Berryman says, because those on a crime scene learn information known only to law enforcment, the medical examiner, and the perpetrator. That sort of student access is highly unusual, particularly for undergraduates, and it is secured by Berryman’s own reputation.

“If you trust Dr. Berryman,” Detective Mayercik says, “you’re going to trust the people he chooses.”

The inviolable rule, therefore, is no talking -to anyone. “If you’ve done it once, you’re off the team,” Berryman says. “I’m serious about that.” His FASR team is serious about it, too. They are so tight-lipped, he says, they won’t discuss details of a crime scene even with other team members.

The bar thus raised, Berryman raises it further: “Once they get on the team, I will do whatever I can to make them succeed. Whatever I can.” Which means he pushes them to do research as undergraduates. he pushes them to teach, to attend meetings of the American Academy of Forensic Science (AAFS), and to present papers, not just at MTSU but nationally. With interest in forensics exploding and grad programs rejecting smart but inexperienced students, competitive graduates don’t just need a bachelor’s degree, Berryman says. They need a curriculum vitae.

Standing Out

Take student Alicja Kutyla, who came to Berryman with no anthropological training and no forensics experience, just the dream of a doctorate in forensic anthropology, inspired by Dr. Bill Bass and the Body Farm. By the time she graduated from MTSU, she didn’t have a resume; she had a CV.

She had been published; she had worked crime scenes and autopsies; she had earned a national forensics award based on her joint research with Berryman, which they presented at a meeting in Washington D.C. She’d also won a prestigious fellowship from the Smithsonian Institution.

She did all that in two years. She’s now completing that doctorate at UT-Knoxville.

Kutyla’s success is a testament to her own intellect and determination and to Berryman’s calculated guidance. A joint citizen of Australia and Poland, she enrolled as a master’s student in biology at MTSU, where she asked Berryman to help her reach her goal.

Doctoral programs in forensic anthropology typically don’t accept biology majors, Berryman says; he quietly doubted Kutyla could make the cut. “And I got that impression,” Kutyla recalls. “But all I wanted was for him to tell me what I needed to do to get there.”

Berryman obliged, turning over a research project he’d shelved for lack of time. he says he watched as Kutyla ran with it. “And I thought, ‘OK, let’s make a plan to get you a Ph.D. in anthropology,'” he says.

Kutyla remembers a checklist; Berryman remembers a strategy. She should expand the project he’d handed her by studying a collection of bones at Vanderbilt. Then she should develop the project further by studying skills at the Smithsonian. And while she’s there, she should get to know a few people and make sure they knew her. People such as Dr. Douglas Owsley, the head of the Smithsonian’s Division of Physical Anthropology, whose good reference would carry weight.

“It’s a chess game,” Berryman says, “and I position my students.”

Ultimately, of course, Berryman’s students position themselves. Kutlya applied for and won the Smithsonian fellowship on her own. Owsley, impressed, approached her about a collection of anthropometric data taken by Germans in occupied Poland. “Dr. Owsley felt that someone should use this date set for research, but they had not been available to the general public,” Kutlya says. “He thought that I would have the best shot at gaining access to these data, as I’m a Polish citizen. The date will the subject of her doctoral dissertation.

Like Kutyla, many of Berryman’s students are now in graduate-level forensics; others are already in the workforce, like Denise Martin of the State Medical Examiner’s Office.

Meanwhile, Berryman is encouraged by the steady stream of smart, motivated students attracted to MTSU’s forensics program. (One is so smart that if she gets a test question wrong, he checks to make sure he keyed the answer in correctly.) “I see so much potential in these kids; sometimes, I don’t think they see it in themselves,” he says.

Building Momentum

Last fall’s launch of a bachelor’s-level forensic science major further broadens that potential. While Berryman’s focus is fieldwork, the new forensic science major focuses on lab analysis, encompassing areas like DNA, trace-evidence, and chemical analysis. It’s a fast-growing field; forensic technologies are constantly advancing, and lab analysts are in high demand, says Dr. George Murphy, chair of the Department of Biology, who helped develop the course curriculum. “There’s a huge need,” Murphy says. “There is probably double the number of forensic labs now than there were 10 years ago.”

As MTSU’s first forensics class completes year one of study, it is a perfect complement to the premier program that Hugh Berryman has put together. Along with FASR and FIRE, the new program is just another step in the process of establishing and increasing MTSU’s national standing in forensic science. It, too, can be viewed as a chess game -and here, as with his individual students, Berryman is positioning his pieces to win. MTSU

FIRE Starter

Dr. Hugh Berryman founded FIRE, the Forensic Institute for Research and Education, to offer training and education to law enforcement and other groups whose work involves forensic science (including a summer camp for high school students). He also likes to involve his higher-level forensics students, who both teach and learn from the professional alongside them.

“As they begin to excavate, you’ll hear the student, who’s had archeological experience, saying, ‘No, hold your trowel like this.’ And you’ll have law enforcement saying, ‘Nope, you’ve got to get a photograph of that before you move it.’ So there’s another layer of training going on there, based on people’s experiences.”

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST