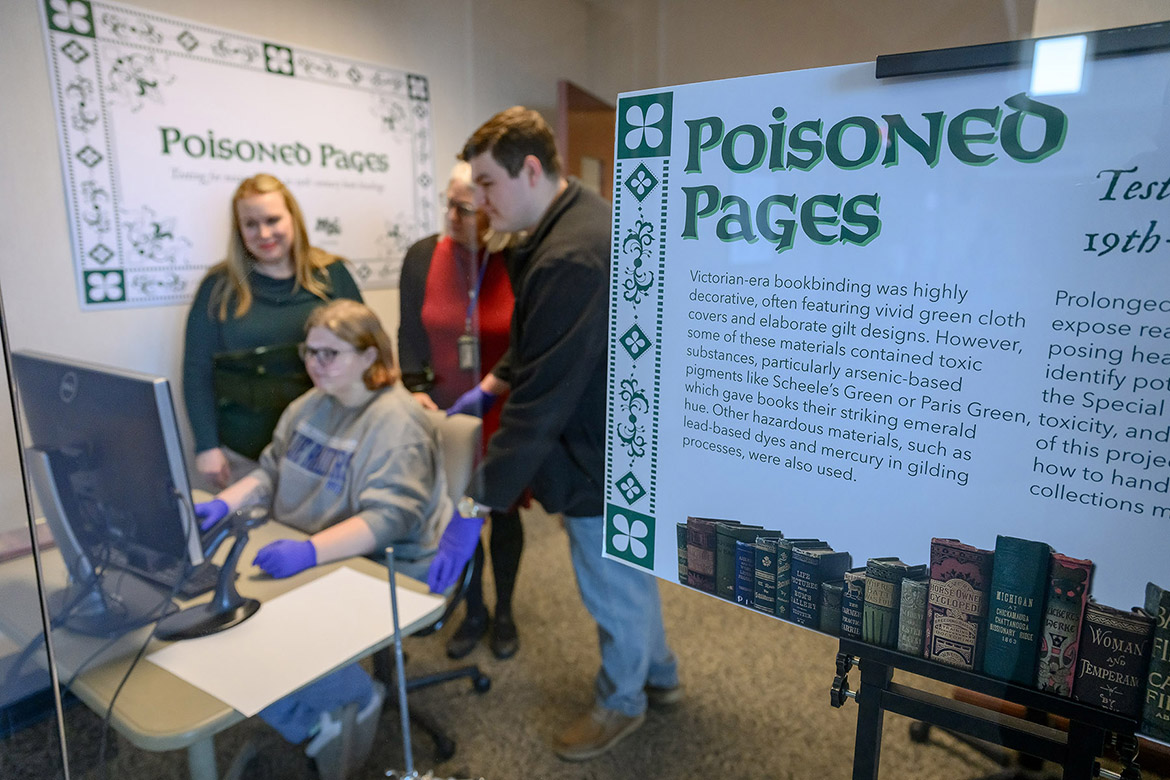

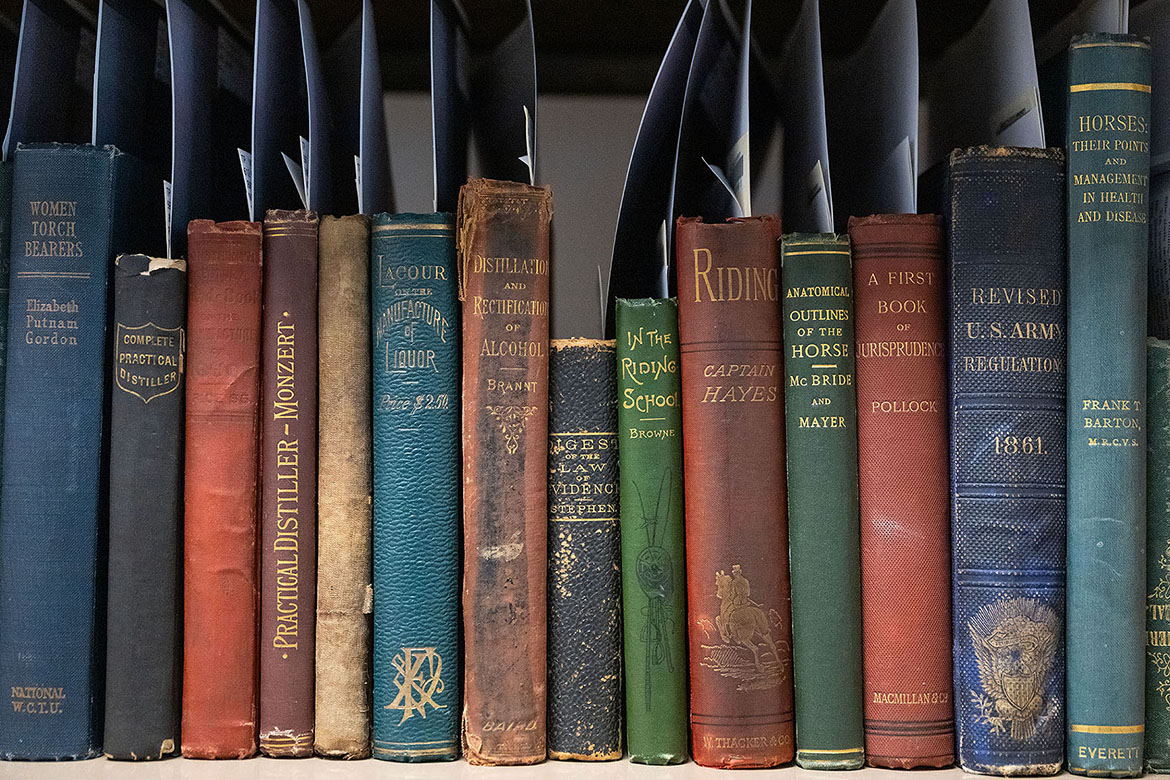

MURFREESBORO, Tenn. — Some of the beautifully bound Victorian-era books in the Special Collections at Middle Tennessee State University’s James E. Walker Library may hide a dangerous secret.

Around 1,200 of these elegantly crafted books from the 1800s — once prized for their vivid colors — could contain pigments made with toxic compounds and heavy metals, explained Special Collections librarian Susan Martin.

“A good portion of our collection — about 14% — are 19th-century books,” explained Martin, who heads up the library’s repository for rare, unique and fragile materials.

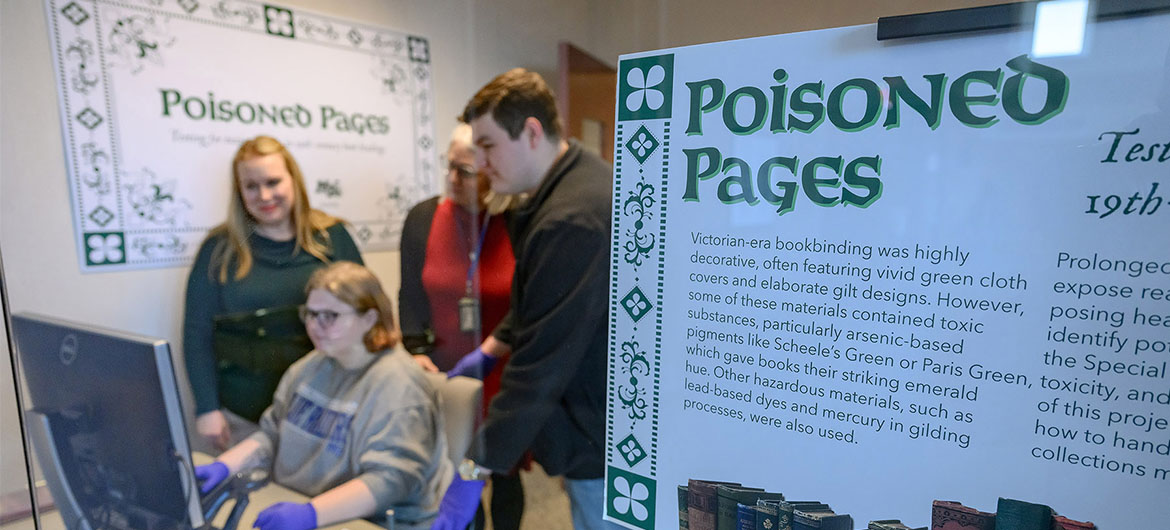

Through a University Research and Creative Activity, or URECA, grant, a team of MTSU students in the fall 2025 undergraduate research course with chemistry instructor Sarah Pierce and Jessie Weatherly used modern technology to test over 30 books that are preserved in Special Collections.

“It’s been lovely partnering with the Chemistry Department and the students have been great to work with. We loved being able to collaborate with them,” said Martin, who served as primary investigator on the URECA grant — the first one Walker Library has been awarded. “We would not have been able to do this without their partnership.”

Testing potential hazards

To identify potential hazards, students painstakingly investigated whether historic books in the university’s collection contained materials such as arsenic, lead, mercury and chromium, advancing both campus safety and hands-on undergraduate research.

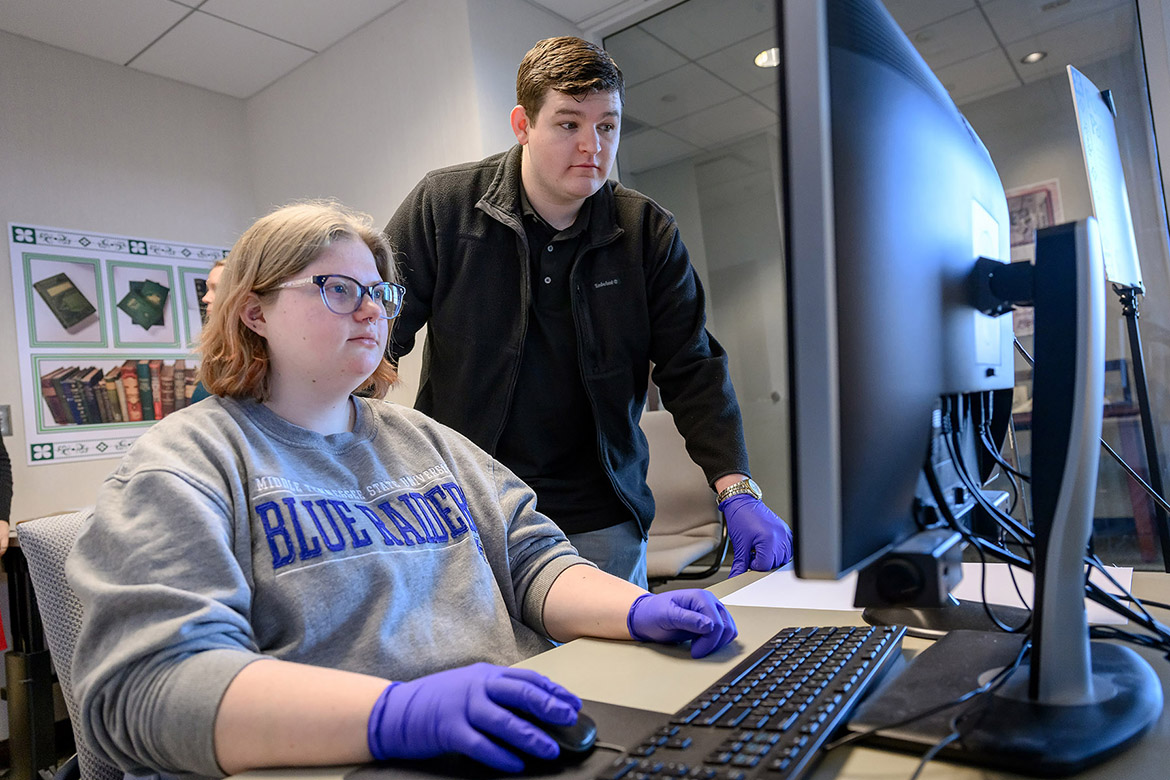

“They try to test different pieces of each book, from the spines and covers to inside where there can be pigments in the marbled endpapers of the inside of the book,” Martin said. “It takes a while to scan each book because there are multiple portions they are testing.”

Martin and Special Collections curator Susan Hanson were inspired to find answers after learning about “The Poison Book Project,” a collaboration between the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Delaware and the University of Delaware to identify and catalog books known to contain these dangerous pigments.

“If it’s contained, it’s OK. But once it begins to degrade, it can get into the air, which could happen,” Hanson said, comparing the risk to asbestos, which can be harmful if the particles are airborne or ingested.

Collaboration is key

Pierce’s work teaching chemistry through art and color led her to Special Collections to find the 1960s landmark textbook, “Interaction of Color,” by Josef Albers. As conversations turned toward pigments, the librarians raised concerns about some of the collection’s “poison books.”

“Everything actually started with Engage, a program that requires an out-of-the-classroom experience,” Pierce said. “I love getting students out of the classroom and helping them make connections to other parts of their lives and across campus.”

Pierce then approached Jessie Weatherly, laboratory specialist in the Department of Chemistry, to explore whether MTSU had the tools needed to analyze rare books safely.

“I told him that ‘Special Collections is asking if we can test books for heavy metals. I think we could do it using XRF, but I’m not sure,’” Pierce recalled. “He immediately said, ‘Yes, we have three,’ and that’s how the project got started.”

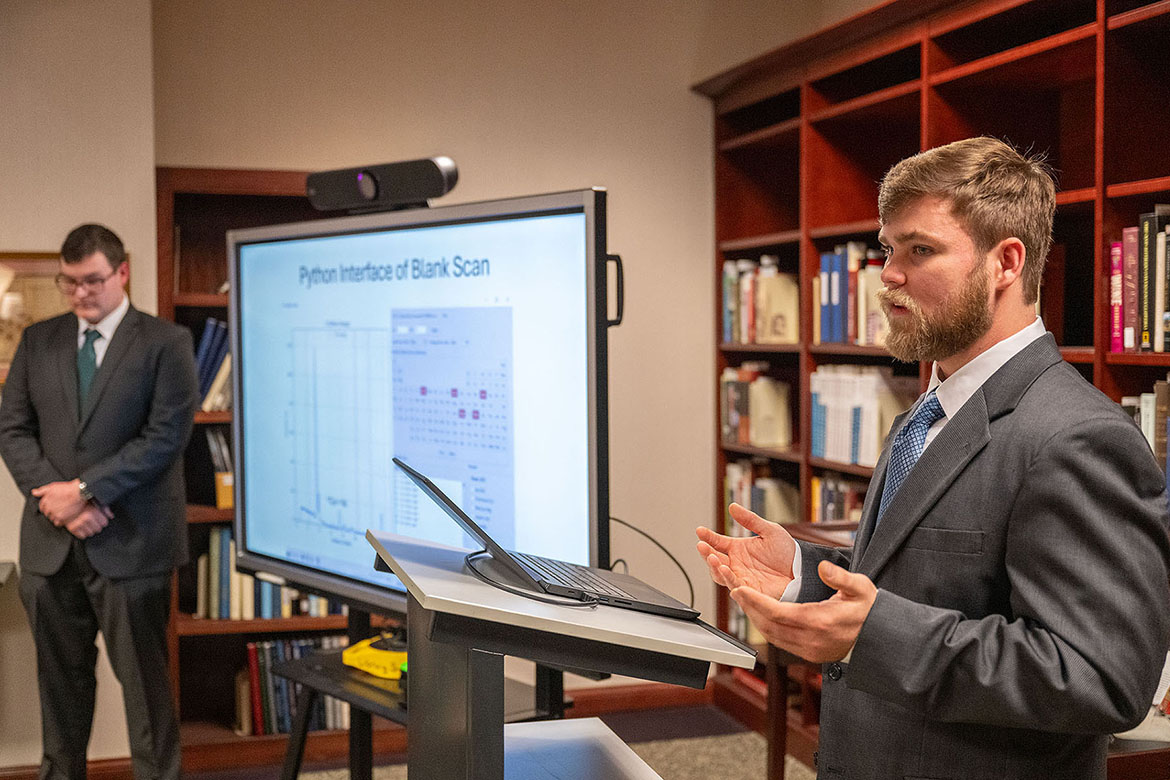

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, or XRF, is a nondestructive analytical technique that identifies and quantifies the elemental composition of a wide range of materials by bombarding them with high-energy X-rays to create an elemental “fingerprint.”

“When we expose certain atoms to high-energy X-rays, they are excited. As they return to their ground state, they release that energy as a photon, which the XRF can detect. Fortunately, each atom has its own unique spectrum, which can be used to identify it,” Weatherly explained.

Student participation essential

Weatherly recruited three undergraduate students — chemistry majors Ethan Coyle and Brantley Harriman and forensic science major Brittney Cupp — who volunteered soon after the project was announced.

“I’m a big fan of history, so when I learned I could explore lesser-known history through a chemistry perspective, I was really intrigued,” said Coyle, of Murfreesboro, who took the course and participated in the project in his final semester at MTSU. “After learning about the project, I went to Special Collections that same day to understand the overall goal.”

After researching pigments historically used in bookbinding, Coyle said he was eager to join the project.

“Once I got home and started looking into the pigments and chemicals used in these books, it became clear that this was something I wanted to work on,” said Coyle, who is now a graduate student in chemistry at MTSU.

Funded by the URECA grant, the student team tested 34 books from Special Collections, and 33 showed the presence of toxic elements.

“We’re mostly finding chromium and lead, which is interesting,” Pierce said.

Harriman, who served as co-lead during his final semester, said the project closely aligned with his coursework and career path. He now works as a clinical lab specialist at Thermo Fisher Scientific in Wisconsin.

“A lot of the chemistry and biochemistry I use now is what I learned in school,” said Harriman, who is now working with instrumentation he learned how to use while taking a class under Weatherly.

Because the project involved rare books, Harriman said care and accuracy were essential.

“There’s a big responsibility to make sure we’re scanning things correctly and getting the right results,” said Harriman, of Powell, Tennessee.

Cupp, of Seymour, Tennessee, supported data collection and reviewed results while also creating educational posters explaining pigment chemistry and research methods. She will continue on the project this spring.

Cupp said the project gave her valuable laboratory experience and helped clarify her career interests.

“It definitely gives me a lot more experience than I had, especially in different fields,” Cupp said. “Any type of lab experience — especially for DNA — is what a lot of people are looking for.”

Cupp also said her interest in the project was personal.

“I love books and I love learning history of these pigments,” Cupp said. “Every single one of them has a different history.”

The interdisciplinary team met weekly and worked closely with Special Collections staff to ensure safe handling of materials. At the end of the semester, Coyle and Harriman gave a PowerPoint presentation, “Poisoned Pages: Testing for toxic elements in 19th-century book bindings,” at Special Collections as their final project before graduating in December 2025.

The research will continue this semester with Cupp and newly recruited students Olivia Sanders and Laurel Thompson, with plans to test more books in the coming years and look at how the heavy metals could transfer to skin.

Special Collections offers gloves and masks for any patron who wishes to use them when handling materials.

“Not only has this project been beneficial for the library, but this project has been real work for the students and will look great on their resumes,” Martin said.

— Nancy DeGennaro (Nancy.DeGennaro@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST