The people who built monuments, renamed streets and created a children’s campaign to tout the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy have never hidden their intent, historian Karen L. Cox says.

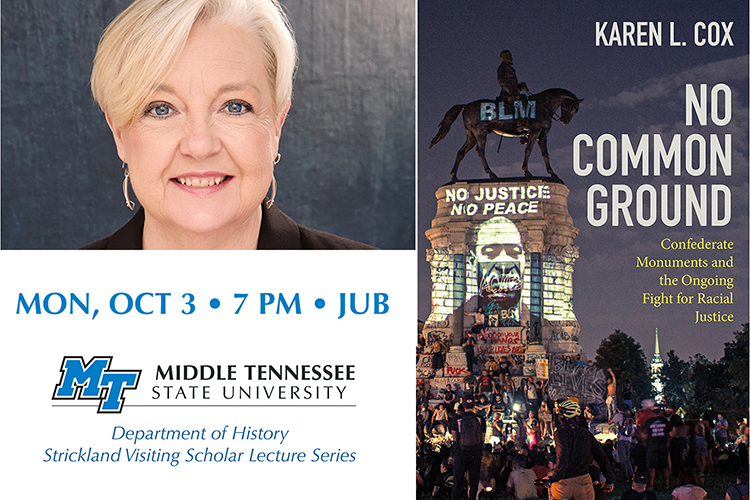

“Southerners in the early part of the 20th century didn’t build these monuments to spite Northerners. For them, this was about redeeming their reputations, the reputation of their ancestors, making sure that going forward, white Southerners still held on to the values that they believe, that their Confederate ancestors fought for: white supremacy,” Cox, a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and author of “No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice,” told an in-person and online audience Oct. 3 at MTSU’s fall 2022 Strickland Visiting Scholar Lecture.

“This was about control for them. This is still about controlling a population that they consider second-class citizens. In recent years, I don’t think that people are attacking the monuments to ‘get back at’ anybody. They’re attacking the monuments because they believe those actually symbolize something that kept their ancestors enslaved, … something that continues to harm our community to this day.”

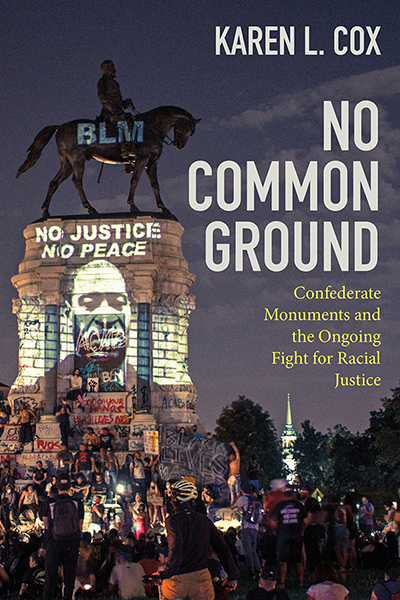

Cox, who also is founding director of the UNC graduate public history program, published her fourth book, “No Common Ground,” in 2021 to trace the history of the controversial shrines and why white men and women erected them to mark their “Lost Cause” mythology and what they saw as their continuing supremacy.

In her MTSU talk, Cox explained that the memorials began cropping up shortly after the Civil War in what she calls the “bereavement phase” of small obelisks and markers in public cemeteries. They grew in size and number near the 50th anniversary of the conflict as the builders made the markers more ornate to support their Jim Crow legislation.

The civil rights movement in the 1960s, and the war’s centennial, saw another wave of Confederate memorials erected across the South as white supremacists sought to intimidate their Black fellow citizens. Anti-monument sentiment grew over the next decades as Black Americans took their rightful places as business and community leaders and won elected offices.

Monument proponents fought back with gerrymandered elections and “heritage commissions” that banned renaming or removing Confederate-themed tributes. The “Black Lives Matter” movement’s emergence in 2013 helped convince growing numbers of Americans to demand the removal of Confederate monuments.

“Confederate monuments have been built in every decade since the end of the Civil War,” the professor pointed out, adding that 750 to 800 statuary existed at one point. “Once Reconstruction was practically over, 1875 to 1877, Southern states kind of reassumed control of their legislatures and their local governments, and they began what I would call the celebration phase. And that begins around … the cults of Robert E. Lee.

“They were like, ‘We’re going to build this monument. We’re going to build it right in the middle of town!’ And they move out. These monuments come outside of these cemeteries and into a public setting.”

Location wasn’t the only priority, Cox said. She pointed to a photo of the massive 85-foot-tall monument to Lee in New Orleans and the 1884 dedication ceremony at its base featuring thousands of celebrants and crowds of children “dressed in the colors that form a Confederate battle flag on the stands. Those were known as ‘living battle flags,’ and this would be part of the ritual of monument unveiling,” she said.

‘More insidious than the monuments themselves’

The United Daughters of the Confederacy, founded in Nashville in 1894 and formed from smaller, localized groups who’d organized the memorials from the cemeteries just after the war to the city squares, ushered in what Cox called the “vindication phase” of Confederate recognition.

“The Daughters … didn’t just say, ‘We’re honoring these men.’ They’d say, ‘We want to vindicate our ancestors. We want to vindicate those men in the building of these monuments’ and all the other activities that these women were involved in,” the professor said.

The UDC was also behind much of the pageantry associated with the memorials.

“At these unveilings, they referred to those children as ‘living monuments,’ because the UDC, as much as it honored these soldiers, was really a forward-looking organization, and they were very much interested in shaping the future generations of white children in the South,” Cox said.

They did that with a group called “Children of the Confederacy,” for whom they had “developed a Confederate ‘catechism’ for children to study that were like call-and-response questions about the Confederacy.”

The UDC convinced communities to name public schools after Confederate heroes, then went inside the schools and hung battle flags and portraits of those men and pushed to have the Ku Klux Klan regarded as postwar heroes.

“I don’t ever want to lose sight of the fact that really, in some ways, that is more insidious than the monuments themselves, because they’re training people to think like they do,” Cox said.

“When these monuments were unveiled, the speakers say pretty much the same thing, that children ought to be taught to emulate their Confederate ancestors. In speech after speech after speech and unveiling after unveiling, they tell you what the monuments mean to them and what they think their purpose is. And it’s not just about honoring the past. It’s about building these monuments as signposts for the future and for future generations.”

Cox pointed specifically to Tennessee’s 2013 “Heritage Protection Act,” which bans moving, taking down or renaming any memorial that is or is located on public property without permission from the Tennessee Historical Commission.

The measure has been cited in the state’s refusal to allow MTSU to change or remove the name of its military science classroom building, which has carried Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest’s name since 1958. Unlike every other building on the campus named for a person, Forrest has no direct connections to the university.

“The Heritage Protection Act is the thing that’s really distinguished Tennessee from other states for quite a few years,” she said. “You have 70 monuments in the state of Tennessee. … But the Confederate memorial landscape is more than monuments. You can get rid of a monument, but you still have all kinds of things that are named for Confederates. Of course, it doesn’t fix the underlying problem, which is the systemic racism.”

MTSU’s Department of History in the College of Liberal Arts sponsors the twice-yearly Strickland Lecture series. The Strickland Visiting Scholar Program helps MTSU students meet with renowned scholars whose expertise spans a variety of historical issues.

The Strickland family established the program in memory of Roscoe Lee Strickland Jr., a longtime professor of European history at MTSU and the first president of the university’s Faculty Senate.

For more information about this lecture, please contact MTSU’s Department of History at 615-898-5798 or visit www.mtsu.edu/history/strickland-scholar.php.

— Gina E. Fann (gina.fann@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST