Those who think they know reggae music are likely in for an education when they read The Encyclopedia of Reggae: The Golden Age of Roots Reggae.

by Gina K. Logue

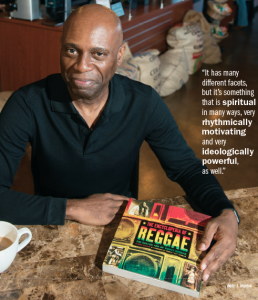

Those who think they know reggae music are likely in for an education when they read The Encyclopedia of Reggae: The Golden Age of Roots Reggae. Written by MTSU professor Dr. Mike Alleyne, the encyclopedia provides a colorful, 352-page study of the reggae genre, covering it from A to Z and from the late 1960s up to the mid-1980s.

Alleyne’s book is one of the most recent contributions from a department that is constantly working to further explore and expand its field. Beverly Keel, newly appointed chair of the Department of Recording Industry, is not bashful about the quality and reputation of the recording program. The former senior vice president of media and artist relations with Universal Music Group–Nashville, who graduated from MTSU herself in 1988, says while other institutions have emulated the University’s recording industry program, “We did it first, and we did it best.”

president of media and artist relations with Universal Music Group–Nashville, who graduated from MTSU herself in 1988, says while other institutions have emulated the University’s recording industry program, “We did it first, and we did it best.”

“It has been the nation’s leading recording industry program,” Keel says. “And we are poised now to take it to the next level. We have some amazing faculty. We have book authors. We have Grammy winners. We have professors who write the manuals for hardware and software. As the music industry changes, we are eager to lead the way.”

As one of those authors/professors, Alleyne, who was born in London to parents who were natives of Barbados, says he wanted his book to be authoritative enough to satisfy knowledgeable lovers of the genre but accessible enough to entice casual fans to want to know more.

“It’s very difficult to get most audiences to look beyond Bob Marley,” Alleyne says. His compilation, though, is designed to help readers do just that. The work includes a timeline, best-of lists, and essays on artists, labels, and producers, along with other aspects of the genre’s influence, including Rastafarianism and marijuana. It’s not a coffee-table book in the traditional sense, but how can it be when the subject—a style of music that incorporates politics and spirituality in every beat—can hardly be called traditional.

Asked to define reggae, Alleyne says, “It has many different facets, but it’s something that is spiritual in many ways, very rhythmically motivating, and very ideologically powerful as well.”

Reggae, Alleyne says, is the first music from people considered “Third World” to penetrate major Western commercial markets. The 1970s seemed to be a halcyon era for reggae influence on Western pop hits, including Paul Simon’s “Mother and Child Reunion,” Johnny Nash’s “Stir It Up,” and Eric Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff.” Eddy Grant’s “Electric Avenue” from 1982 is something of an anomaly because, while the hit is more of a rock track with a reggae beat, Grant had established his reggae credibility with straight reggae hits in Europe, Alleyne says.

According to Alleyne, reggae’s influence in American music is as strong now as it was then, but its visibility is not as great. He says the musical influence actually works both ways, with American music sometimes influencing reggae style, but the profitability of the music is a little more one-sided. “It’s interesting to see how a rock group can integrate reggae elements and achieve this incredible commercial success, but reggae groups who will integrate rock are never able to do that,” he says.

A case in point is a series of tribute albums to the Police’s 1997–2008 catalog that features notable reggae performers. “The artists were willing to participate in that because they welcomed the opportunity to reinterpret the interpretation of reggae that the Police had come up with,” Alleyne says.

While insisting he is not a reggae purist (he also teaches an occasional course on Jimi Hendrix), Alleyne says he would like to see more reggae artists become as well known and widely respected as the rock artists who appreciate reggae enough to appropriate it for their own music. The ethnocentrism behind that lack of renown is irksome but not surprising to Alleyne. After all, reggae is an art form firmly planted in the anticolonial politics that led to Jamaica’s independence from Britain in 1962.

Alleyne points out that many musicians had been harassed for their Rastafarian religion and were not part of the political or economic establishment anyway. They understood the average Jamaican. Men were chased down in the street and tackled, and their dreadlocks were cut off, as much a sign of racist intimidation as cutting a Chinese man’s queue, thus putting him in bad stead with the ancestors he worships. Reggae has always been political, he explains, but the industrialized nations to which the music is exported don’t necessarily absorb its political import.

“Reggae has this aura of exoticism that isn’t always clearly connected by sectors of the audience to a harsh political and economic reality,” Alleyne says.

And yet, musicians in Jamaica seem to find a way around their economic circumstances to produce the music they love. Some of Alleyne’s encyclopedia’s most compelling photographs are of Ampex reel-to-reel machines under spartan, tin-roofed buildings.

“It’s actually quite remarkable that the music has had such great historical resonance, because it was done with the bare minimum of equipment,” Alleyne says, noting that some of reggae’s best music was made with two-track or four-track machines while recordings in wealthier nations were made with 16-track or 24-track machines.

With department experts like Alleyne, who can reveal the history, politics, religion, and circumstances behind the music, it’s no wonder Keel calls recording industry “the greatest major on campus.”

“You get this great rock-and-roll degree, if you will,” she says, “but you also get a great basic college education with English, history, science, and all the things to make you a well-rounded person.”

Thanks to Alleyne, majors in the University’s Recording Industry program can now add a fourth “R” to their college education—reggae.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST