One of the world’s oldest crops seems altogether new again. As Tennessee, and the nation for that matter, redefines the much-maligned hemp plant, Volunteer State farmers and universities are angling to take advantage of an exciting new era for the oft-misunderstood plant.

The hemp industry is certainly not new; but, as Tennessee has moved toward legalization of the farming, processing, and research of industrial hemp, MTSU has positioned itself smartly for opportunities in science, agribusiness, and more.

Overcoming First Impressions

At the word “hemp,” many people raise eyebrows. But just as two different corn plant varieties yield popcorn and corn-on-the-cob, the same is true of cannabis.

To be clear, industrial hemp is not marijuana.

Legally, hemp is defined as any cannabis plant variety that contains less than 0.3% of the psychotropic compound THC. Most marijuana plants in demand today contain THC levels from 5% to 20%. Thus, one cannot get “high” on hemp.

The plant’s stalk, woody core, and seed, however, can be used to make literally thousands of things. The plant, which was used extensively in America until the 1950s, is now growing again in Tennessee.

“It’s pretty unique in its ability to be used in a lot of very different ways,” said Dr. Nate Phillips, associate professor in MTSU’s School of Agribusiness and Agriscience. “From fiber to fodder to food to bioremediation, there’s so much out there.”

Tennessee legislators passed a bill in 2014 allowing farmers to grow industrial hemp in the state. A total of 54 Tennessee farmers did just that, growing a wide variety of the plant in the 2015 growing season. For 2016, 63 farmers secured licenses to plant, grow, and harvest industrial hemp.

A new hemp bill which passed the Tennessee General Assembly in the most recent 2016 session now allows for the processing of industrial hemp. Importantly for both MTSU and its Tennessee Center for Botanical Medicine Research (TCBMR), the new law also expanded opportunities for universities to conduct hemp research.

“Tennessee is evolving, and our lives will be different as a result of these bills passing,” said Dr. Elliot Altman, TCBMR director and head of MTSU’s Molecular Biosciences Ph.D. program. “The future is bright for this.”

“The industry in general has lot of promise,” added Phillips. “Although some hiccups on regulations and infrastructure development still have to get worked out.”

A Student Success

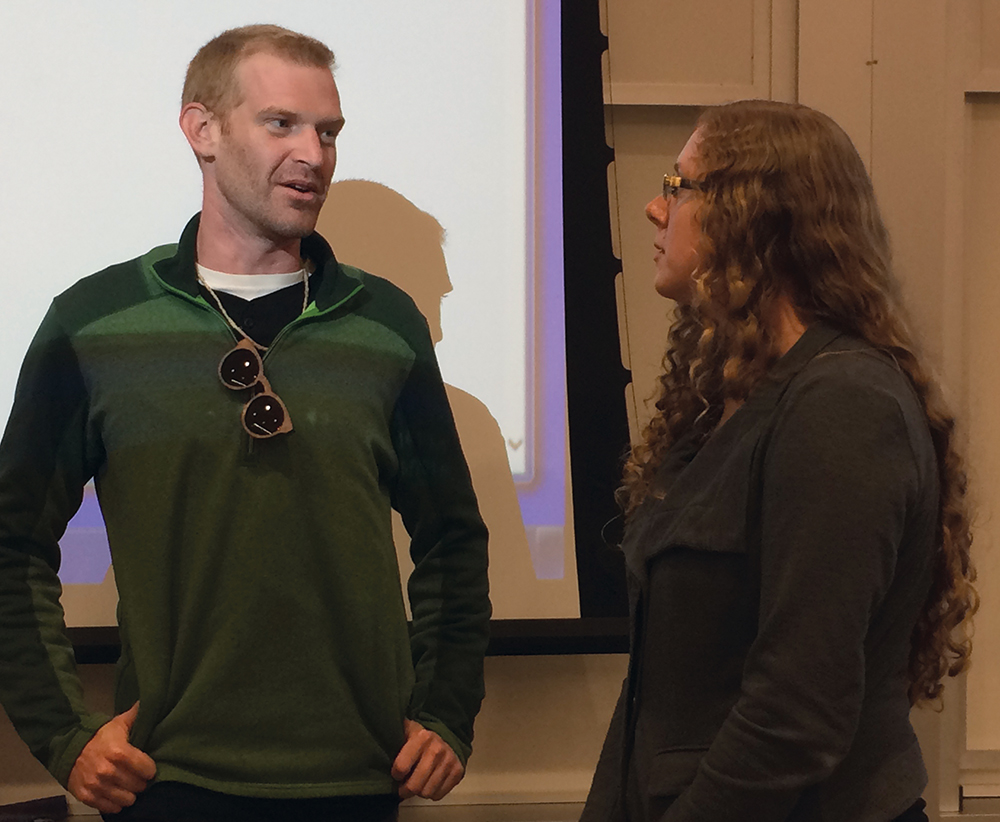

Both Phillips and Altman credit MTSU graduate student Clint Palmer with both ramping up the University’s excitement about being involved in industrial hemp in Tennessee and in taking clear steps to be an academic leader in the state.

“All credit goes to him to bring it here,” Phillips said.

Palmer spent six months of his final undergraduate year seeking grant money for his hemp research agriculture project. In the summer of 2015, Palmer conducted a trial growing seven varieties of hemp—six of them for seed and one for fiber.

“Clint had the idea and followed through,” Phillips said. “He created that excitement about research and also brought in other younger people to participate who were not even in agriculture.”

Importantly, Palmer also piqued Altman’s interest in the medicinal qualities of hemp oil after the student met with the professor to ask about them during Tennessee’s first hemp growing season in 2015.

“I started pulling together that research and soon thought, ‘Wow,’ ” Altman said. “There is ample scientific research which shows that a number of non-psychotropic cannabinoids—compounds found in hemp seed—have antibacterial, anticancer, antiepileptic, antifungal, and immunomodulatory activities.”

“That’s the root of our excitement,” Altman summed up.

Growing the Industry

Before changing his major from environmental engineering to agriculture, Palmer spent time in Colorado building a tiny house out of hemp-crete, just one of the products that can be made from hemp’s woody core.

Products from the stalk include everything from the aforementioned building material to mulch, boiler fuel, clothing, shoes, and carpet. In addition, seed from the hemp plant can be used nutritionally and clinically.

“The hemp extract market appears to be $400 million worldwide,” said Altman, a lifetime pharmaceutical developer with decades of intellectual property development expertise.

MTSU now works alongside organizations such as the nonprofit Tennessee Hemp Industries Association (TNHIA) to educate politicians and the public about the potential uses and financial upsides of industrial hemp.

“After the bills passed, farmers, entrepreneurs, and everyone fascinated by hemp starting asking us questions,” Altman said.

And as Tennessee farmers increasingly figure out both the nuances and financial upsides of growing hemp, they see clearly how they stand to gain.

“A very small group of farmers is doing it right now and they are creating history,” said Colleen Keahey, TNHIA founder and president. “They want to be the first.”

During Tennessee’s first growing season in 2015, farmers planted experimentally.

“Farmers used seed, some of which was from Canada, and figured out what could go wrong,” Palmer said. They learned answers to questions like “What are the pests that can affect growth?” and “What’s needed to increase yield?” Most of those farmers are growing 1–5 acres to total about 1,185 acres of hemp in 34 Tennessee counties. Other states growing industrial hemp in 2015 included Kentucky, Colorado, Vermont, and Oregon.

“In the end, farmers want to know how much they’ll make,” Palmer said. “So they’ll try it on small acreage to see how it does. Most do a rotation of corn, soy, and wheat. Hemp fits

in perfectly with that. It has the same needs.”

Domino effect

With the new legislation fresh on the books permitting hemp processing and research, both Tennessee farmers and University researchers are gearing up for higher levels of activity. Palmer said a greenhouse will be built on campus property to grow subspecies. Early research will isolate the content of each plant. Phillips said he is hopeful and foresees opportunities to coordinate with TCBMR on the production side.

A clear new path to processing and distribution will also open doors for entrepreneurs.

“There will be lot of movement in this area,” Altman predicted.

Because of TCBMR’s proven ability to isolate and identify bioactive compounds in plants, it could be the vehicle to certify farmers’ products as well.

“The major problem with the hemp flower extract industry has been that consumers don’t know what they are buying as there are no certified products available that guarantee the bioactivity of the hemp cannabinoid extracts,” Altman explained. “The Tennessee Center for Botanical Medicine Research would like to understand which cannabinoids have what medical properties and whether the cannabinoids can act together to generate more potent activities. This would lead to the creation of superior hemp flower extracts whose bioactivity can be certified.”

“TCBMR can be the evaluator and can certify bioactivity. We’ve proven we’re very good at assays (bioactivity tests) and can certify any product made,” Altman added.

“Anything TCBMR can do to help the farmer, we want to do.”

The purpose of TCBMR is to deliver compounds that can help people. The applied science appeals deeply to Altman and to his graduate students who want to make a difference

in people’s lives.

“I think all the students would say that this matters: ‘I’m doing something important,’ ” he said. “All of our students come in loving medicine and love the idea they might be creating a drug to help somebody somewhere.”

Palmer plans to start research on hemp as he pursues his doctorate in Molecular Biosciences under Dr. Altman’s tutelage.

“Once you educate with facts, it’s not hard to understand the potential for hemp,” Palmer said. “I think it can really open up doors for ag research and bring students into agronomy.”

| MTSU |

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST