A coaching legend’s role in making MTSU a color-blind campus

by Bill Lewis

Evening the Playing Field: Legendary MTSU track coach Dean Hayes is credited with integrating MTSU athletics. He also deserves credit for integrating campus, and, more recently, for helping internationalize MTSU.

MTSU’s track and soccer stadium is named for Coach Dean Hayes, but the greatest monument to his accomplishments is not a structure; it’s the diversity of the students who come to the University.

When Hayes first stepped onto the campus in 1965, almost all of the 5,500 students enrolled were white. Olivia Woods, the University’s first black student, had graduated. A few African American athletes played sports, but no African American scholarship athlete was competing on a varsity team.

The campus offered no black fraternities or social organizations. A plaque honoring the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, still stood on campus.

As he took on the task of recruiting the best athletes possible, Hayes unconsciously took on another role—as an agent of social change who participated in breaking the color barrier.

“When I got down here [from Chicago], they were still fighting the Civil War,” Hayes recalled during a 2003 interview for the MTSU Oral History Collection, archived at the Gore Center. “I blundered through it,” he said of the process of integrating his teams. “It wasn’t much of an issue for me.”

Forty-six years later, the campus looks like America. More than 15 percent of students at MTSU are African American. Others are Hispanic, Asian, American Indian, or members of other minority or ethnic groups. It all started with a phone call Hayes made soon after being hired as MTSU’s track coach.

“The very first guy I recruited was a black guy. It cost me 35 cents for a phone call,” he recently recalled.

The young man who answered the phone, Jerry Singleton, became the first African American varsity scholarship athlete at MTSU.

Others followed as their quietly competitive coach, who describes himself as “kind of defiant,” made more phone calls. When those athletes arrived on campus, so did their girlfriends, sisters, brothers, and friends.

“I never thought much about it because I didn’t do it on purpose, but it changed the complexion because it allowed minorities to have acceptance” on campus, Hayes says. “It has consequences you don’t think about.”

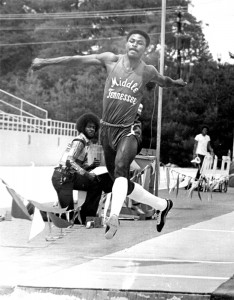

Hayes’ reputation for competitiveness (he throws away second-place trophies) and fairness attracted other black athletes to MTSU, says Tommy Haynes, an All American in the long and triple jumps.

“I turned down a scholarship [offered by another school] so I could go to MTSU and train with Coach Hayes. That’s how much respect I had for him,” Haynes says.

Two years after graduating in 1974 and beginning his military career, Haynes briefly returned to Murfreesboro to train with Hayes for the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. He never felt like he was bumping against a color barrier on campus.

“Success breeds success when you have the same goal in mind,” Haynes says.

“Success breeds success when you have the same goal in mind,” Haynes says.

African American athletes felt welcome in Murfreesboro, but trips to events deeper into the post–Jim Crow South revealed a different reality. Haynes, who retired as a major after a distinguished career in the U.S. Army and is a member of the Blue Raider Hall of Fame, recalls being denied service in restaurants because of his race. Before a road trip, the coach tried carefully to map out restaurants and motels along the route that were known not to discriminate.

Meanwhile, times were changing with the arrival of more African American students on campus. Kappa Alpha Psi, a Greek letter fraternity with predominantly African American membership, began a chapter at MTSU. Hayes, who was the fraternity’s first advisor, is still approached by confused pledges who have to memorize the original members’ names.

They wonder whether this white coach really is one of the chapter’s founders.

As time passed, a hound dog named Ole Blue replaced Nathan Bedford Forrest as the University’s mascot. And one day then-president Sam Ingram walked out of his office and took down the plaque honoring Forrest.

“If you didn’t live through those times, I don’t know how much you’d appreciate it,” Hayes says of today’s diverse campus.

But taking diversity for granted may be the greatest victory of all, Hayes adds.

“Their parents and grandparents went through that so today’s kids wouldn’t have to. That bothers me because I saw it and I think these kids should appreciate it,” says Hayes. “But they’re not supposed to appreciate it.”

What is appreciated at MTSU is Hayes’s seminal role in making MTSU the diverse environment it is today.

[Editor’s Note: Hayes also deserves much of the credit for the increased presence of international students at MTSU. Under his guidance, international athletes began arriving from Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, and other places in the 1970s. Joe O’Laughlin, a middle-distance runner from Ireland, says being recruited by Hayes in 1978 opened up opportunities that he never would have had. “It changed my life totally, being on a team with members from all walks of life,” he says, adding that the experience positively shaped his views of other races and nationalities.]

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST