A folklorist studies a widely misunderstood Appalachian tradition

by Allison Gorman

Years before the National Geographic Channel sent film crews to Middlesboro, Ky., to document the life of preacher Jamie Coots for the show “Snake Salvation,” Associate Professor Patricia Gaitely (English) was there doing some documenting of her own. Equipped with a simple recorder and camera, a notebook, a Bible, and sometimes a tambourine, she traveled to Coots’s church and other small congregations in the rural Southeast to immerse herself in the culture of snake handling. She’d long been fascinated by this unusual Appalachian tradition, and she hoped to interview women in the insular, generally patriarchal denominations in which snake handling is practiced. What she learned changed many of her assumptions about these people, whose lives bear little resemblance to reality TV.

Gaitely began with more than a passing knowledge of the subject. Raised Anglican, she started attending Pentecostal services at age 22, before she left her native England for graduate school in Alabama. “I was familiar with fairly lively expressions of worship,” she says. “I believed in the supernatural, in healing, and speaking in tongues, that kind of thing.” But snake handling was a different matter. Only a few Pentecostal congregations—usually identified as “Holiness” churches—believe in a scriptural mandate (Mark 16:18) to take up serpents as a sign of faith.

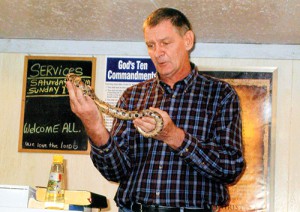

Gaitely at Pastor Jimmy Morrow’s church in east Tennessee holding a snake box containing a copperhead. (Photo by Rhonda L. McDaniel)

The first known snake handler practiced in East Tennessee in 1909, but the tradition is older than that, Gaitely says. It spread throughout southern Appalachia, where it still attracts a vibrant subculture with hundreds of adherents. When Gaitely joined MTSU in 2006, she saw an opportunity to explore that subculture from its birthplace. “As a Christian, I am very interested in how others of the same faith express that faith,” she says. “I’m also interested in snakes and belonged to a reptile club in Alabama. So it was an intriguing combination for me.”

The Internet and fellow researchers led her to Del Rio, Tenn., Sand Mountain, Ala., and Middlesboro, to churches that seemed remote from the world, although they weren’t far from the interstate. “Many are in quite depressed areas,” she says. “Every time I went to Middlesboro, it seemed like something else in town had closed down.”

When first visiting a church, Gaitely usually sat in the back, near other women. (“I would never have presumed to sit behind the pulpit with the men who were sitting there,” she says.) To interview the women, however, she typically went through a male “gatekeeper.” But once she had access, what she saw and heard surprised her. The women acknowledged their traditional biblical roles as subordinate to men, yet they felt spiritually empowered. “I found that many women were active in these services, rather than passive,” Gaitely says. They couldn’t preach, but they “testified” (often a slim difference), sang and played music, and handled snakes as the spirit led them.

They also seemed socially empowered, as Gaitely noted in an article for the North Carolina Folklore Journal. They set their own standards for biblically appropriate dress and behavior. And because their congregations functioned much like extended families, sharing practical and sometimes even financial support, child rearing was less onerous and lonely than it can be for many mothers, especially those facing economic hardship. That might explain why many of the women Gaitely met weren’t raised in the tradition, as she had assumed, but had joined it voluntarily. As she concludes in her article, “The way of life they have chosen, and the way these women have chosen to express their faith, grants them a degree of freedom, autonomy, and self-expression that some with more material resources might find enviable.”

Television has portrayed these communities as anything but enviable, as Gaitely predicted it would when she was visiting the Del Rio church and the BBC arrived to film a service for its documentary Around the World in 80 Faiths. “I remember saying, ‘I know what they’re going to focus on. They’re going to film the toothless person or the person dancing around with no shoes on’—and that’s pretty much what they did.”

Gaitely has never seen “Snake Salvation,” but she understands its appeal; fascination with snake handling sparked her own research. (The subject got fresh media attention when Jamie Coots died of a snake bite in last year, and again when his son Cody, who succeeded him, suffered a nonfatal bite as well.) But she says focusing solely on snake handling — which, if it happens at all, might take up 10 minutes of a two-hour service — misses the larger picture, which is about people searching for spiritual authenticity. That’s a tradition as old as humankind.

Folklorist Trish Gaitely isn’t the only MTSU professor with an academic interest in serpent handling. Dr. Jenna Gray-Hildenbrand, assistant professor of religious studies in the Department of Philosophy, is frequently quoted by news outlets that cover the practice, specifically regarding legal aspects of the Tennessee law passed in 1947 that banned it. The last formal legal challenge to the law occurred in 1975, when the Tennessee Supreme Court weighed public safety over religious liberty and confirmed that serpent handling was too dangerous to be legal.

Photos courtesy of Trish Gaitely.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST