by Allison Gorman

Larry Sanderson had planned to ride his technical career with Enron straight into comfortable retirement. Instead his employer famously went south in 2001, taking his 401(k) with it. After searching for a new career and a more sustainable retirement plan, Sanderson went south too. He left Ohio for Tennessee, to grow American ginseng on his own small slice of the Cumberland Plateau.

It was a leap of faith for someone in his 50s, especially since ginseng must be cultivated over several years, not a single season. However, having grown up tending a quarter-acre garden in Montana, Sanderson liked the idea of living off the land, especially the wild, wooded piece of it he and his wife found on the Appalachian “ginseng belt.”

They had looked for land in several states, but as soon as they toured the 10.5-acre tract between Monteagle and South Pittsburg, they were sold.

“It’s back off the road,” Sanderson said. “There’s no sound here at all, and we’ve always been around a freeway or a railroad. Man, it’s so quiet here. I love it.”

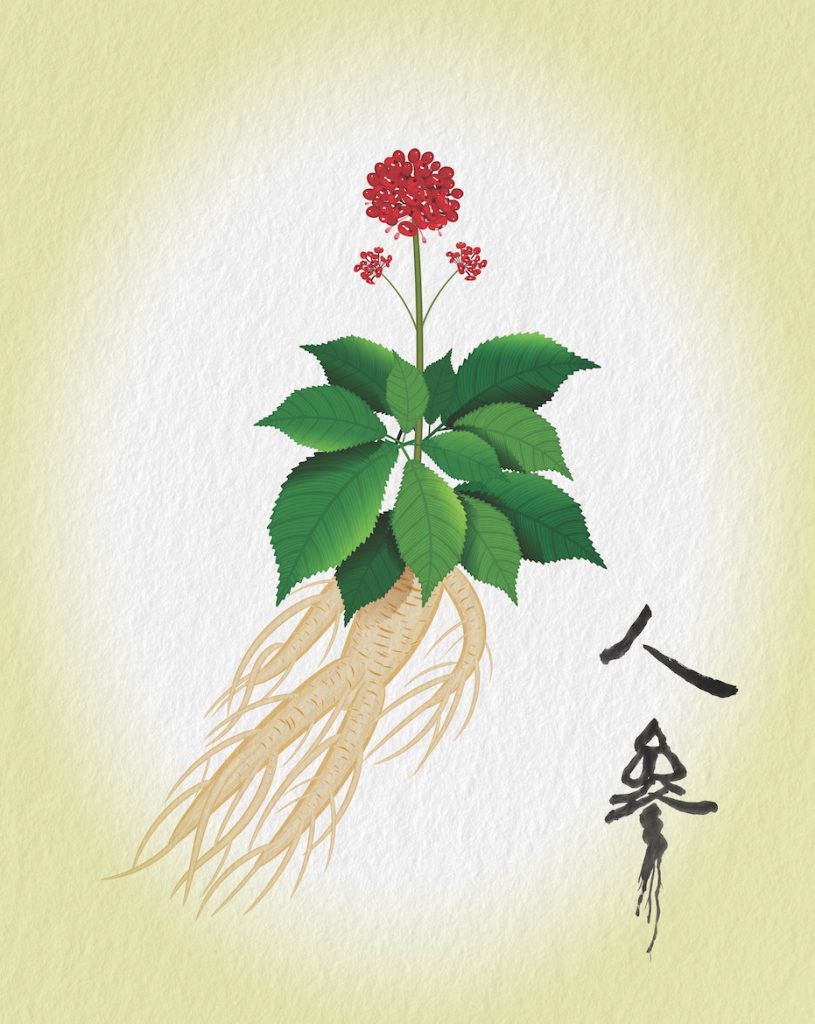

He also loves his earning potential growing wild American ginseng, whose mature roots fetch sky-high prices for medicinal use in Asia.

Digging for ginseng has been a tradition for generations of Tennesseans. They’ve fed their families by heading to the deep woods in the fall. Yet the work is hard and often danger-ous, and it usually doesn’t provide a stable income, especially now that ginseng is getting harder to find. Despite longtime government regulation of digging, which is all but forbidden on public land, American wild ginseng is an endangered species.

By cultivating it in its native habitat—the environment thought to give its roots their medicinal potency—Sanderson doesn’t just want to make money. He wants to make a living.

“Wild-simulated” farming isn’t new, but it’s new to American ginseng, said MTSU Professor Iris Gao, director of the International Ginseng Institute (IGI) on campus. With financial backing from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), she’s been working to advance the farming model, which could do more than rescue Sanderson’s retirement or even save an endangered species. It could bring new life to rural communities in Appalachia.

GROWING A NICHE INDUSTRY

Much of the work Gao does is grassroots, providing one-on-one support for budding ginseng growers, with information on the logistics and techniques of wild-simulated methods. Meanwhile, her research team is developing scientific technologies to make those methods more efficient and effective. Through the IGI, they bring together all the stake-holders in the wild ginseng industry—growers, dealers, researchers, and government regulators—collecting and disseminating information online and through workshops and symposiums.

But the larger goal is to reengineer the economics of wild American ginseng, to create a new, sustainable supply to meet global demand.

The demand for ginseng has always been strong in Asia, where it’s been used as medicine for 2,000 years. But Gao says the market is growing as science is beginning to substantiate the health benefits long attributed to ginseng root. In Chinese medicine, it’s prescribed for side effects of chemotherapy, such as fatigue and nausea, as well as for chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. Now, its medical efficacy is being explored through peer-reviewed research and clinical trials.

Iris Gao, director of MTSU’s International Ginseng Institute

In response to that demand, farmers in Wisconsin have adapted standard field cultivation methods to produce ginseng on a large scale.

But field-cultivated ginseng is less valuable than wild-harvested because it’s considered less potent. Gao said there have been few published studies comparing their potency, so her research team published one of its own. Indeed, her team found that wild ginseng contained far more active ingredients than field-cultivated roots.

Gao believes multiple factors could account for the difference, including variations in climate, soil, topography, surrounding vegetation, and even tree species in the natural canopy. A major factor is that field-cultivated ginseng is harvested after three or four years, for profitability, but wild-harvested ginseng must be at least seven years old—and some found roots are decades older than that. The longer the root grows, the more active ingredients it accumulates, Gao said.

“The plants that grow in the wild don’t have fertilizers, they don’t have pesticides. They have to fight their own way to survive,” she explained. “They have to fight tree roots and rocks and naturally occurring pathogens, and in the process they develop secondary metabolites. Those are the active ingredients in ginseng.”

Naturally grown ginseng is more desirable even when it’s not used for medicinal purposes, she added. “If I drink ginseng as tea, or cook it with food, I would like it to be organic.”

A 2020 report published by the USDA’s Southern Research Station bears that out, finding that wild American ginseng sells for 10 to 25 times more per pound than field grown.

A DISAPPEARING TRADITION

Between overharvesting and loss of habitat, wild ginseng is fast disappearing. In Pennsylvania, once part of the ginseng belt, the species is entirely gone.

Through its Natural Heritage Inventory Program, Tennessee’s Division of Natural Areas is trying to prevent that from happening here.

Ginseng is very much part of the heritage of Tennessee, which has been exporting it to China since the 18th century. Of the 19 states that can legally harvest and trade ginseng, Tennessee is the third-largest exporter.

According to Caitlin Elam, the state ginseng coordinator, all of Tennessee’s exports are reported by ginseng dealers to be wild harvested from private land with landowner permission, as digging on state land is now prohibited. The USDA report also finds that counties with high harvest rates have high poverty and unemployment, especially in Southeast Appalachia, where wild ginseng provides “an economic safety net.” But the current supply model isn’t sustainable for plants or people.

“To conserve valuable wild native plant products while also improving local livelihoods, wild cultivation and good stewardship practices must be promoted,” the report concluded.

This solution introduces a new category of stakeholder: ginseng growers like Sanderson, who can plan and plant for maximum profitability. Elam notes that for a $250 permit application fee, growers could increase their earnings by becoming licensed ginseng dealers, who buy, bundle, and export the roots in bulk.

Plus, wild farming suits the ethos and economics of rural Appalachia, Gao said. It preserves the forestland and requires minimal investment—mostly seed and sweat equity.

Promoting wild farming will pay dividends for Tennessee, too. Murat Arik, director of MTSU’s Business and Economic Research Center, found that encouraging local cultivation of ginseng in Tennessee could generate $32.5 million in net annual income, with an economic impact of up to $87.3 million.

A NATURAL SOLUTION

Recognizing its economic potential, the USDA has invested heavily in Gao’s work—in 2017 with a $148,000 grant to promote and support wild farming of ginseng in Tennessee, then in 2021 with a research grant of $455,000.

The first grant led to Gao’s founding of the IGI. The second grant, combined with $300,000 from MTSU, will fund development of biocontrol agents to prevent blight. Along with principal investigators from Penn State and the University of Virginia, Gao is leading a multi-institutional team that includes some 20 undergraduate students.

“The major diseases in ginseng are soil-borne fungal diseases,” Gao said. “They can spread quickly, wiping out a crop in a very short time. Imagine getting a fungal disease in your fifth or sixth year that wipes out all your plants. It would be a disaster.”

Gao said some growers have to spray with fungi-cides weekly or even daily, from April through September. Sanderson sprays once a month, spending $800 a year on chemicals. “That’s a lot of money when you’re a small farmer,” he said.

When the natural technology is available, he’s ready to make the switch. In the meantime, he is eager to try the new hybrid seed Gao is working on, one with a shorter maturation time.

“Iris is developing better strains, stronger strains, trying to help growers like me,” he said. “I had to go on the internet; that’s all I had. So I made a lot of mistakes and lost a lot of money up front.”

According to Elam, the new technologies being developed at the IGI can make growing ginsenga more viable and appealing business, and that business can help save an endangered species.

LESSONS LEARNED

Sanderson met Gao in 2017, the year he sowed his first 100,000 seeds following the advice of Farmer Google. He’d read that ginseng grows where ferns grow, and that ginseng won’t grow under pines. His tract on the Cumberland Plateau had a lot of pines.

A forester offered to remove them for $2,000 but would have decimated the hardwood canopy.

Sanderson figured out that pines are OK if you clear the needles away, but ferns don’t play nice with ginseng. From that first crop he has just 500 plants. From his second he still has 10,000.

The next year he tried three different planting methods. One of them “came up like a carpet,” he said, but was prone to blight. From that crop he learned not to sow ginseng seeds so close together.

Sanderson’s 2018 crop recently yielded his first “three-prong,” the distinctive leaf pattern of a maturing plant. “It’s just as cute as can be,” he said. Still, you don’t harvest three-prongs; you wait for four or five. He expects his first harvest in 2026.

PEOPLE HELPING PEOPLE

Growing ginseng is a patient business, but the setbacks and the waiting are easier when you’re not going it alone. Sanderson has been sharing what he learns with Gao. She uses the information in her research and for workshops and symposiums hosted by the IGI, which is now the hub for a burgeoning, collaborative community of Tennessee growers.

“This isn’t about me, really—this is about me and 170 other guys,” Sanderson said.

Last year, Sanderson had a different kind of setback.

“We had four years of planting when my heart went south on me,” he said.

The diagnosis of a genetic condition, and the possibility of surgery, scuttled Sanderson’s plans to plant in 2021. Undeterred, he and Gao are working on a backup. She’s researching goldenseal, another promising candidate for wild farming that matures in just two years. Her students can help put the rhizomes in the ground.

People helping people. Looks like that Tennessee tradition is here to stay.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST