Now in her early 80s, child Holocaust survivor Sonja Dubois of Knoxville, Tennessee, still carries the pain of so many survivors of one of history’s greatest atrocities. But she continues traveling the state to share her story, ensuring that society never forgets the traumatic ripples that affect her and so many more, even today.

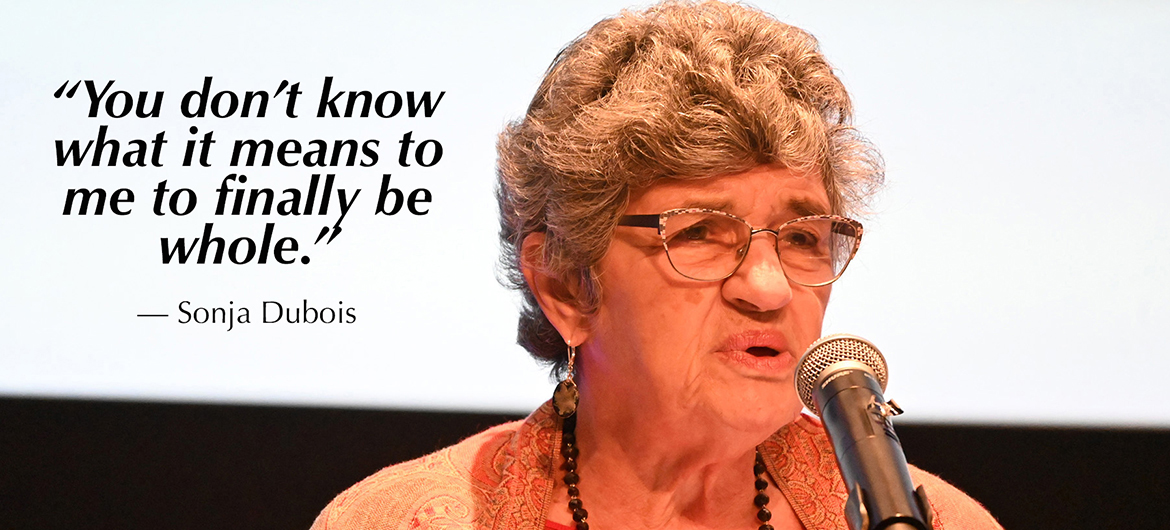

“I am a ‘hidden child.’ It has taken me most of my life to discover who I am and where I belong,” Dubois told an attentive audience recently inside MTSU’s Student Union Ballroom during her talk to close out the university’s 14th biennial Holocaust Studies Conference. “I’m also one of the last witnesses to share information about the Holocaust.”

Dubois shared her heart wrenching survival story — on the way to a Nazi concentration camp, her Jewish parents arranged for family friend, Dutch artist Dolf Henkes, to have her placed (hidden) with a Dutch Christian family to save her — and her yearslong search as an adult to uncover the truth of her identity and understand her Jewish heritage.

Born in 1940 in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, Clara van Thijn was only a small child when her biological parents, Sophie de Vries and Maurits van Thijn, were transported to the notorious Auschwitz death camp in 1942, where they were murdered soon after their arrival. Dutch couple Willem and Elisabeth van der Kadenwas the foster family that took Clara in and raised her as their foster child Sonja — giving her a new birthday along with a new name — without telling her initially about what happened to her real parents.

The Van Thijns were among the 6 million Jews that Nazi Germany systematically exterminated from 1941 to 1945 on the false premise that people of Aryan heritage represented a “master race” and were the only ones fit to survive. Other victims of Nazi persecution included homosexuals, ethnic Poles, Roma and Afro-Germans.

‘To finally be whole’

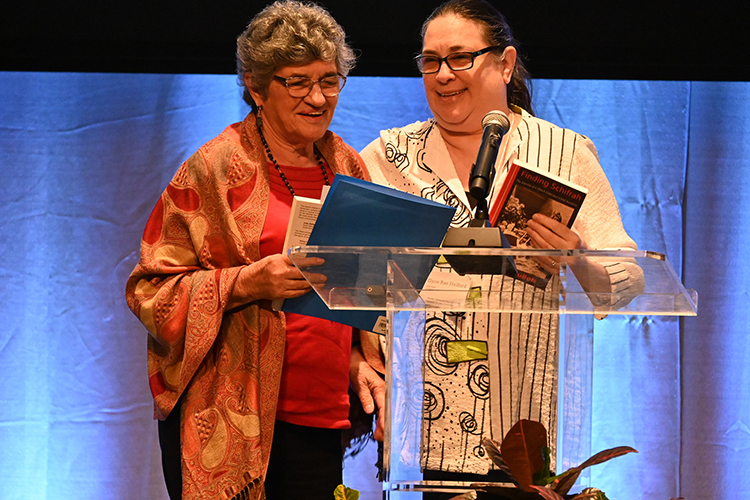

During her MTSU talk, “Finding Schifrah: A Holocaust Child Survivor’s Journey and the Making of a Memoir,” Dubois took the audience through her journey to uncover her roots, come to grips with her family’s history and embrace the publishing of her resulting memoir, “Finding Schifrah,” a few years ago.

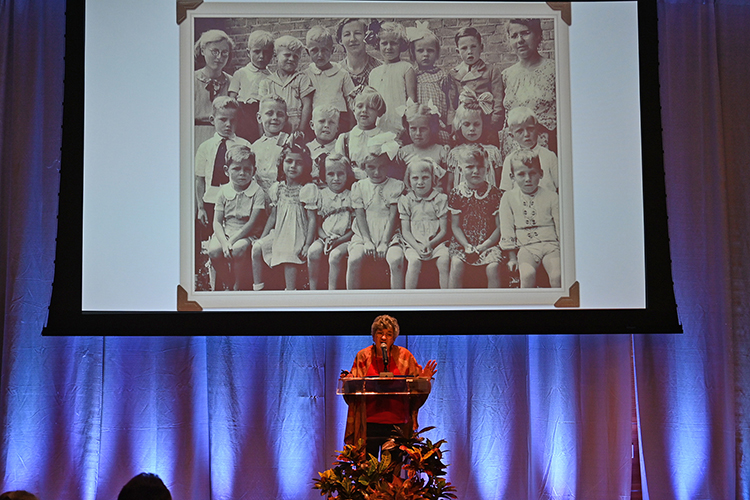

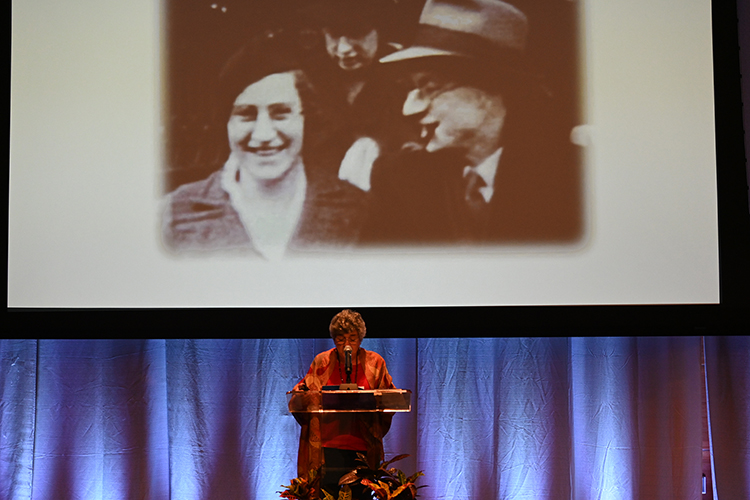

During her PowerPoint presentation and talk, among the images Dubois shared was the first photo of her biological parents she’d ever seen — a discovery she didn’t make until she was 60 years old.

She also shared unearthed photos of Jewish aunts and uncles; a photo of Canadian troops who helped liberate Holland from the Germans, signaling the end of World War II (she recalled the troops throwing out chocolate bars and bubble gum, she preferring the gum whose smell still evokes memories today); a school photo of her and her classmates, her dark curly locks standing in striking contrast to the mostly blonde Dutch children pictured with her.

“You don’t know what it means to me to finally be whole,” said Dubois, who emigrated to the U.S. with her family when she was 12 and would go on to marry and raise a family of her own.

Reflecting on her early childhood, Dubois noted that when she was 3 or 4 years old, “I knew that Mom and Pop weren’t Mother and Daddy,” adding that she picked up bits and pieces of conversations from adults around her that reinforced her suspicion as she grew up. “I knew that these folks who were taking good care of me weren’t Mother and Daddy.”

‘A last-minute rescue’

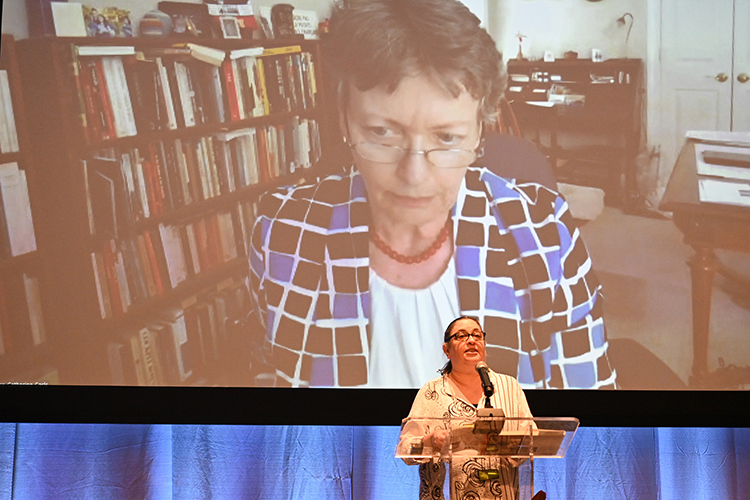

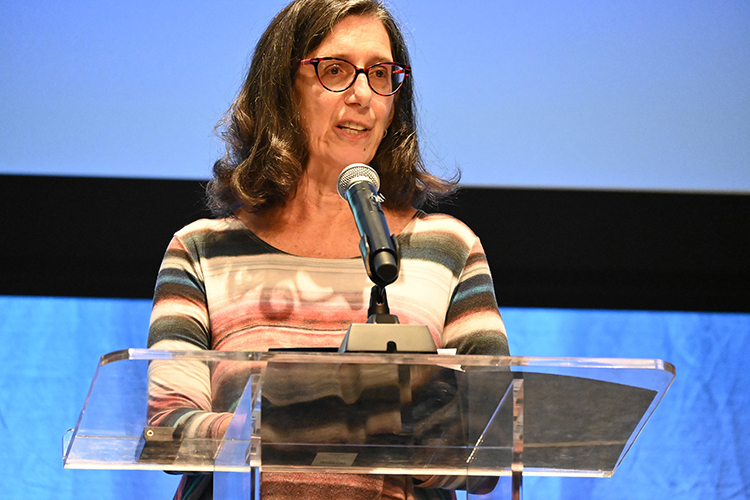

Dubois was joined for the MTSU discussion by the co-editors of her memoir, Alice Catherine Carls, via Zoom and Hanno Weitering, who gave an on-stage presentation about his exhaustive research efforts to unearth details of Dubois’ Jewish roots.

Carls, the Tom Elam Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Tennessee, Martin, worked with Dubois to glean from her personal journals and creative letters written from the perspective of her Jewish mother to develop a framework for the memoir.

Carls spoke of the origins of their collaboration, a chance meeting between her and Dubois at a conference almost a decade ago that happened because it was a rainy day. “Rain” was one of the five Rs that Carls laid out to the audience as forming the progression of their collaboration to get the memoir published: rain, respect, redaction, resistance, and resolution.

“I wanted to respect Sonja’s voice, but I also wanted to respect her privacy,” Carls said, “because when you interview someone who has had a traumatic past and who has had a past as complex as hers has been — and the secrets kept from her — I felt that I had to respect certain boundaries and I could not push her to say certain things that were too painful. …”

Weitering, a Dutch physics professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, helped develop the memoir further by using his significant research prowess and ability to translate documents to connect many historical dots about Dubois’ Jewish roots, including Dubois’ timely removal by Henkes from a chicken coop on a Holland farm where she and other Jews were hidden.

Also born in Rotterdam a few decades after the war, Weitering knew Dubois through a local women’s club in Knoxville that his wife was involved with and that sometimes met at the Weiterings’ home. Dubois approached him one day to translate a note from Dolf Henkes written in Dutch and his involvement grew from there.

Weitering quipped that as a physicist, he can depend on the established laws of nature to help inform his research and conclusions. Historical research, however, and the inherent unpredictability of humans, made his work for Dubois quite challenging.

“Through this journey, trying to dig up some facts about Sonja’s past and her family, I just realized how much more difficult it is to draw conclusions from what people may have thought, what they might have done. And every time you think you’ve figured out the story … then there’s a new fact and you’re back to square one,” he said.

Weitering took the audience through a litany of PowerPoint slides showing digitized documents and letters with fading signatures, handwritten notes and maps of various locations in and around Rotterdam that help put the pieces of Dubois’ past together — including Henkes recognizing that the chicken coop wasn’t a safe location and relocating Sonja to a hiding place back in Rotterdam where she was eventually rescued by the Dutch parents who would raise her.

“It really was a last-minute rescue,” said Weitering, noting that the ruins of that chicken coop are still standing, displaying a photo of Dubois visiting the site last winter.

‘Let us not be indifferent to racism’

Though the Holocaust Studies Conference was canceled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the event has been a biennial opportunity for scholars from around the world to share their research and insights with students.

Elyce Helford, professor of English and director of the Jewish and Holocaust Studies Minor, told the attendees that it is important for the public “to continually be educated and re-educated about the new facts, the new information that we find, and the new ways of seeing … that’s something that I think Sonja’s memoir has done.”

Helford also noted that Dubois was speaking on the birthday of the late Dr. Nancy Rupprecht, a professor of history and driving force behind Holocaust Studies at MTSU for many years.

In welcoming the audience to Dubois’ talk, Cheryl Torsney, vice provost for faculty affairs and an English professor, spoke of her own deep Jewish heritage, with both sets of her Jewish grandparents immigrating to the U.S. in the early 20th century.

As a child growing up in Youngstown, Ohio, Torsney said she and her family knew Holocaust survivors in her neighborhood, including a local grocer — “We held our breath when we got a glimpse of the tattooed number on his arm.”

Even as the passage of time see more and more Holocaust survivors pass on, Torsney noted genetic research several years ago that suggested that the trauma those survivors experienced in concentration campus could be passed down to their children and perhaps even their grandchildren.

Torsney implored those in attendance to remain vigilant in combatting the antisemitism “that you well know isn’t showing signs of going away.” Citing data from the Anti-Defamation League, Torsney noted that while “white supremacist propaganda dipped slightly in 2021 after hitting a record high in 2020, antisemitic speech jumped 27%. … There’s something in the news every single day.”

Dubois concluded the event by reading excerpts from her memoir, including a section written to her oldest grandson in which she reflected on his interest in learning more about his heritage and her story as a child Holocaust survivor.

“When I talked to your class, it was a most important, difficult lecture. As I looked at you in that classroom, I felt tears burning eyes. After all, I barely escaped the Nazi terror, yet there you were, my first-born grandson. What a miracle! I will never take our lives for granted.

“Suddenly I realized that I am the matriarch of a new family. You know it is a well-known saying, ‘that evil grows when good people do nothing.’ Let us not be indifferent to racism, and I hope you will tell our family about their Jewish heritage when I am gone.” (Watch the video clip below.)

The Holocaust Studies Conference is sponsored by the MTSU Holocaust Studies Program and the College of Liberal Arts. For more information, visit www.mtsu.edu/holocaust_studies/conference.php/php.

— Jimmy Hart (Jimmy.Hart@mtsu.edu)

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST