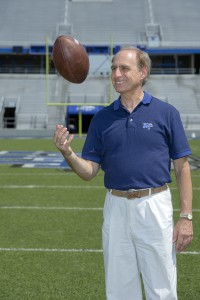

Dr. Mark Anshel works to keep performance anxiety off the field and out of mind

by Amanda Haggard

The smallest man in pads—the field goal kicker—trots out to the 30-yard line. Though only seconds remain in the game, his uniform is spotless. Setting up next to the squatting holder, he takes four measured steps backward followed by three equal steps to the side. Now aligned for the perfect kick, he glances briefly up through the goal posts before bringing his gaze back down to the squatter’s position.

“I can do this,” he tells himself.

As the ball is snapped, he strides forward, locking his back foot before following through with his kicking foot—a fluid two-second motion that sends the ball soaring high into the air and eventually between the goal posts. Three precious points are added to the scoreboard as the crowd cheers. And the kicker’s larger, dirtier teammates begin to pat their comrade on the back as he jogs back to the sidelines.

And if that field goal kicker is truly prepared, according to Dr. Mark Anshel, a professor in the Department of Health and Human Performance at MTSU, all of this has already happened in the player’s head several times with positive outcomes before the game has even started.

“There’s one person who’s totally responsible for success or failure on that performance trial,” Anshel says. “And all eyes are on him. The pressure is insurmountable. His goal is to maintain attentional focus on what’s relevant in the situation, that is, a clean kick, ignoring all extraneous noise and interfering stimuli and to be able to deal with any distractions.”

Anshel teaches courses in sport and exercise psychology, research methods, experimental design and motor behavior. He’s the author of Sports Psychology: From Theory to Practice, now in its fifth edition. Much of his work was spurred by a lack of available knowledge on how an athlete can best cope with stress, which caused him to create literature in an applied area and use research as the basis of application.

Given the rabid nature of collegiate fan bases, there’s usually a lot riding on the leg of the football team’s placekicker. It’s not uncommon for oversized men to fight and scrap and tear each other to pieces for 59 minutes and 59 seconds only to have the diminutive kicker on the squad determine the game’s outcome.

What’s running through a kicker’s mind in such an instance? Is it different for the kicker than for the rest of us in terms of thoughts and emotions?

As MTSU’s resident expert on the psychology of motor performance under great anxiety or stress, Dr. Anshel is well qualified to explain the psychology of one of the most stressful sports moments—the field goal kick.

Getting Your Head Straight

According to Anshel, 70 percent of child athletes in the United States drop out of sports while in school. One primary reason, he says, is their self-perception of “low ability” in competitive athletics.

Where does the negative self-view come from? Anshel says it often comes from negative feedback from coaches, parents, opponents—even teammates—which feeds self-doubt and eventually leads players to drop out, which may only add to the obesity problem in the United States.

“We don’t want our kids dropping out of sport,” Anshel says. “They end up leading inactive lifestyles, put on a lot of weight, and stay sedentary.”

For college and pro athletes, low-ability perceptions are the ultimate recipe for failure. “When an athlete makes a low-ability explanation for their poor performance, they are on their way out,”

Anshel says. And that’s especially true for field goal kickers, who often dictate success or failure for their teams.

Given that burden, most collegiate and professional kickers have certain personality characteristics that allow them to handle their tough job: confidence, the anticipation of success, and a strong belief in mental and physical preparation.

“Their personality traits are based on stability and consistency,” Anshel says. “More than anything else, they are able to manage their emotions very effectively, overcome barriers of booing [for instance], and concentrate solely on the act.” In their mental imagery, there is “always a successful outcome.” Anshel says they “view the kick as a challenge, do not feel threatened by it, and have no self-doubt about their ability to get it through the uprights.”

According to Anshel, even when they fail and miss a kick, the successful kickers he knows are adept at quickly downplaying the negative event in their minds and getting back to positive thinking. When they miss, they “tend not to view themselves as poor players—[instead it] could be bad luck, wind, a poor hold, an awkward hit of the ball. But they park it in that corner called ‘what can I learn from this’ and move on. They’re very good at being able to move on from the lack of success.”

Experience counts, too. Anshel says kickers must also keep a store of memories of positive achievement from which they can recall previous instances of success. He adds that child athletes often have issues coping with stress in sports because they’ve had little or no previous success from which to generate positive images.

“These better athletes at MTSU or even these elite-level athletes have all these positive performances from their history to retrieve and recall and remember and execute mentally,” Anshel says. In addition to expecting success, accessing memories of success, and dismissing past failure as anomaly, kickers also develop a set of mental routines focused on a proper set of procedures to perform in the actual game. They mentally prepare for big moments.

Taking the Game Home

Do such characteristics translate into success in life? Anshel thinks so. While mental preparation is especially vital to tasks like field goal kicking, Anshel says groundwork in building confidence is the key to increasing a sense of purpose and arousal while managing anxiety in any sport—and even in everyday activity.

“Anxiety is a killer of sport performance,” Anshel says. “Anxiety is about threat and worry, and when you’re feeling threatened or worried about ‘what if,’ your muscles tighten up. And when your muscles tighten up, they stop being coordinated.”

Anshel says these coping skills can be transferred to many areas of life—he works with the Murfreesboro Police Department and emergency dispatch in order to teach them the same kind of anxiety management that a field goal kicker would use to perform a game-winning goal.

“You’ve got to manage your anxiety and build confidence,” Anshel says.

That sounds like good advice for anyone

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST