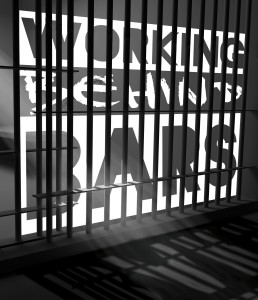

Meredith Dye studies on oft-ignored female population

by Katie Porterfield

As a little girl, Assistant Professor Meredith Dye (Sociology and Anthropology) watched a lot of Scooby-Doo.

As a little girl, Assistant Professor Meredith Dye (Sociology and Anthropology) watched a lot of Scooby-Doo.

“At the end of each show, when they unmask the bad guy or the ghost, they see that it’s a real person, and it’s usually someone they know,” says the 37-year-old Dye, who mentions her affection for the cartoon to help make sense of what’s perhaps an unlikely calling: prison research.

“I have a tendency to see people in prison as people, not for what they’ve done,” she says.

It’s this tendency that fuels Dye’s most recent research on women serving life sentences in prison, a small population (5,000 in the United States) that receives little research attention.

In fact, in 2010, she and her colleague Professor Ron Aday (Sociology and Anthropology) visited three Georgia prisons and surveyed 214 of the 300 women serving life sentences in the state. As far as the pair knows, their data represents the largest sample of its kind. In addition to the fact that female lifers are an overlooked prison population, it’s difficult to get permission to work with them.

“If it weren’t for Ron, I don’t think I would have been able to get access to prisons to collect data,” Dye says, explaining that Aday, who wrote a book on women aging in prison, has a contact in the Georgia Department of Corrections who paved the way for them. “When I was at Georgia [in graduate school], I was discouraged to hear that it took someone 13 years to establish a relationship that enabled him to gain access.”

Teaming up with Aday after joining MTSU is just one of the many experiences that shaped Dye’s interest in prison research. In other words, Scooby-Doo isn’t solely responsible for her “pathway to prison,” as she calls it. As she got older, her concern and compassion for people portrayed as “bad guys” spilled over to her academic career. At Erskine College, where she majored in behavioral science, she helped a Ph.D. student conduct research on deviant behavior in controlled and isolated environments. Between undergraduate and graduate school, she worked as a counselor at a residential treatment center for juvenile sex offenders and found herself asking questions about the environment and its approach to helping patients. While working toward her master’s in sociology with a concentration in criminology at the University of North Carolina–Greensboro, she developed a fascination with those who must live in and adapt to institutions in which their lives are completely controlled. She began to focus mostly on prisons and wrote her thesis and dissertation on factors associated with prison suicides (using secondary data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics). In 2008, after getting her Ph.D. from the University of Georgia, she ventured to MTSU, where she met Aday just as she was beginning to look at gender differences related to suicide in prison.

Teaming up with Aday after joining MTSU is just one of the many experiences that shaped Dye’s interest in prison research. In other words, Scooby-Doo isn’t solely responsible for her “pathway to prison,” as she calls it. As she got older, her concern and compassion for people portrayed as “bad guys” spilled over to her academic career. At Erskine College, where she majored in behavioral science, she helped a Ph.D. student conduct research on deviant behavior in controlled and isolated environments. Between undergraduate and graduate school, she worked as a counselor at a residential treatment center for juvenile sex offenders and found herself asking questions about the environment and its approach to helping patients. While working toward her master’s in sociology with a concentration in criminology at the University of North Carolina–Greensboro, she developed a fascination with those who must live in and adapt to institutions in which their lives are completely controlled. She began to focus mostly on prisons and wrote her thesis and dissertation on factors associated with prison suicides (using secondary data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics). In 2008, after getting her Ph.D. from the University of Georgia, she ventured to MTSU, where she met Aday just as she was beginning to look at gender differences related to suicide in prison.

After working with Aday to gather data, she published “I Just Wanted to Die” in Criminal Justice and Behavior Journal. The article compared suicidal ideation among women before receiving life sentences and then while in prison. Her latest study, “The Rock I Cling To: Religion in the Lives of Life-Sentenced Women,” was cowritten for the Prison Journal.

Dye is far from finished. She’s yet to write a general paper on the characteristics of women serving life sentences, and because her survey contained closed and open-ended questions, she has a wealth of material that should eventually lead to a book. Her findings so far, she explains, are myth breaking in that they don’t fit most preexisting perceptions of who women serving life sentences really are.

“One thing that stands out right away when you meet these women is that they’re like your mom and your grandmom,” Dye says. “They are aging. They have wheelchairs, walkers, white hair, and health problems associated with aging. Or they are middle-aged women who never saw themselves ending up in prison, much less serving a life sentence.”

Unless they are serving life without parole, most women serving life sentences will not be in prison for life. Yet, as Dye explains, they are almost invisible because they comprise such a small population. (Less than one percent of all Georgia inmates are female lifers.)

“What I heard from them over and over again was ‘We are overlooked,’” says Dye. “The prison administration and staff are more concerned about people serving shorter sentences and getting them back into society so they don’t come back to prison.”

“What I heard from them over and over again was ‘We are overlooked,’” says Dye. “The prison administration and staff are more concerned about people serving shorter sentences and getting them back into society so they don’t come back to prison.”

Though Dye readily cites useful and interesting percentages about the women she surveyed (see page 37), she’s quick to point out that her research isn’t just about crunching numbers. It’s also about telling the stories of incarcerated women “nobody seems to care about.”

“I’m not saying these women don’t need to be in prison, but who are they, how did they get there, how are they serving their time? Do I think this particular research will lead to a change in policy or their daily lives? Probably not, but I think we always need to ask ourselves what we’re doing.”

Meanwhile, she thinks she’s exactly where she needs to be. “A professor who does research on gangs told me one time that he always tells the people he interviews that for just a series of different life circumstances, choices, or opportunities, he could be where they are,” Dye says. “I feel the same way. I feel privileged and fortunate. I’ve had a lot of opportunities, and I think this is what I’m supposed to do.”

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST